Woody Guthrie remains a popular presence in protest music, a gunny sack full of contradictions and complications. His legacy is twofold: a political figure in music, a musical figure in politics. He might not have been the first guitar strummer to set lyrics about the struggles of the working man to popular song, but Woody remains the most influential and recognisable protest singer, an inspiration and exemplar for nearly every subsequent generation of musical dissenters. Pretty much anybody who has sung about a president or corporate boss has aligned themselves with Woody Guthrie and his populist ideals.

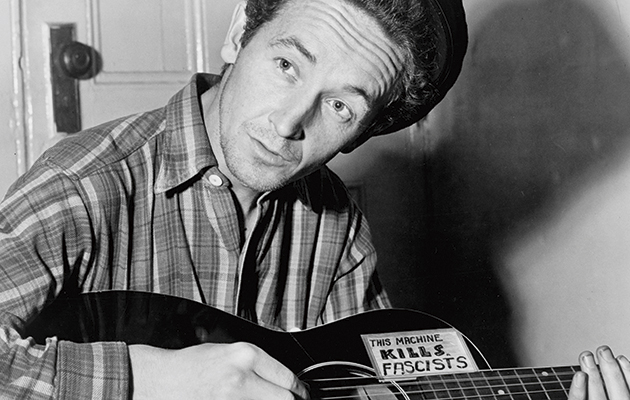

Even 70 years removed from his most active period, he remains politically volatile, even if his politics appear contradictory from the standpoint of the late 2010s. Guthrie was a staunch patriot with a broad definition of American that included not just whites, but minorities and immigrants from every part of the world. He was born into a family with deep prejudicial views (his father reportedly participated in the lynchings of African American men), but Woody eventually rebelled against his upbringing and adopted views that grew more progressive over time. He was a union man who visited migrant camps and mining strikes; a WWII veteran who plastered the military slogan, “This Machine Kills Fascists”, on his guitar, as though music were a weapon. He adopted an exaggerated Okie persona to better sell himself as authentic. He portrayed himself as a loner and a rambler enjoying the quintessential American freedoms of wanderlust and self-determination, yet he loved marches, demonstrations, hootenannies and other communal gatherings of common people. There was glorious strength in numbers.

He loved people, loved hearing their stories, loved hearing about their lives, and that curiosity about his fellow Americans remains highly influential. “To me one of the problems we’re having right now is this lack of empathy toward other people’s points of view and life situations,” says Patterson Hood of the Drive-By Truckers, whose latest LP, American Band, addressed race, class, gun control and other issues head on. “We’ve tried to make that a part of what we do in terms of how we approach our subject matter. Whenever we’ve written about politics, we’ve tried to make it a personal thing, whether it’s one of us or a character or somebody we know. We’ll put them in a situation and let them tell their story.”

Especially in 2017, however, it’s easy to let Woody’s politics obscure the music, to view his legacy as exclusively social rather than artistic. Music was a tool for him, certainly, one that could be used to hold the nation accountable to its founding principles, but it was in many ways an end in itself for a man who was relentlessly, almost obsessively creative. He was a witty cartoonist and surprisingly graceful painter, not to mention a prose writer with an obvious love of words. His newspaper columns and especially Bound For Glory collect curious colloquialisms and bend words into a common American dialect.

His truest medium was song, and he wrote in notebooks and journals everyday, often perusing the newspapers for inspiration. Many of those songs were left unfinished; in fact, only about one tenth of the thousands of sets of lyrics he wrote have ever been recorded. He undertook the enterprise of singing and songwriting with great gravity, yet he also wrote some incredibly funny songs. He didn’t merely write about politics, but also about his kids, his neighbours, his car; he wrote about the Grand Coulee Dam and various WPA projects; he wrote love songs and spiritual inquiries. The world around him was his greatest and only source of inspiration, and it was enough.