Plenty been going on while I've been away on holiday, it seems, not least the auspicious opening of the Rolling Stones' Exhibitionism show that Michael reviewed last week. In the second room of the show at London's Saatchi Gallery, Michael reports, "The history of the Stones is played out across 72 ...

Plenty been going on while I’ve been away on holiday, it seems, not least the auspicious opening of the Rolling Stones’ Exhibitionism show that Michael reviewed last week. In the second room of the show at London’s Saatchi Gallery, Michael reports, “The history of the Stones is played out across 72 screens. The footage begins and ends with fans screaming. It hits the familiar beats: drugs bust, Brian, Altamont. ‘First you shock them, then they put you in a museum,’ says the young Jagger, with one eye firmly on the future.”

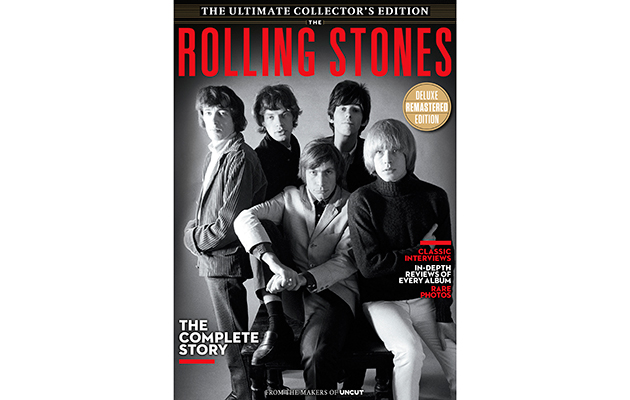

A good time, then, for us to produce one of our deluxe Ultimate Music Guides, with a lavish update of the volume dedicated to The Rolling Stones. The mag goes on sale in the UK this Thursday, but you’ll be able to order our Stones Ultimate Music Guide from our online shop sooner. In it, you’ll find a definitive survey of the band’s storied career, told with the aid of in-depth reviews of every Stones album and a wealth of interviews from the archives of NME, Melody Maker and Uncut. “At the moment and for the next 10 years I’m happy,” Keith Richard (as he was known then) announces in 1964. “Whether it will last, I don’t know.”

Our 148 pages act as testament to the fact that the Stones did what no-one, 50 years ago, thought was possible: make an engrossing lifelong career out of the uncertain, possibly ephemeral business of being in a rock’n’roll band. That this music has been sustained for so long – become embedded in our culture, even – is due, in an enormous amount, to The Rolling Stones. It’s not just the excellence of their music, or their business genius. No, The Rolling Stones set a template for rock’n’roll that was much bigger than music. Rock’n’roll was inexorably hooked up with sex and drugs. It articulated adolescent rage, rebellion, boredom and pettiness better than any other art form. It at least pretended to be dirty, provocative, confusing, not a little menacing.

And it found its purest embodiment in their skinny, uptight white bodies. The Beatles might have been charming, easier to assimilate and, perhaps, musically superior. But the Stones were far more successful at capitalising on the principle of a counterculture. They were A Threat. Five young men who were taken to court for urinating in the street, who were regarded with fear and despair by right-thinking parents and who, with the canny assistance of their manager until 1967, Andrew Loog Oldham, made nastiness marketable. What could be easier to pull off and yet so radical, so appealing and so lucrative?

“I always imagined The Rolling Stones lasting, one was just not aware of in which form,” Oldham told me in 2002, from his home in Bogota, Colombia. “They were very professional and dedicated from the first moment. I told them who they were and they became it. They wore the bad boy tag like a suit of armour, and drew a veil over how professional they really were.”

It’s strange how a desire to do whatever you want can pan out. One of the most radical innovations of The Rolling Stones is that, with every day of their continuing existence, they force us to look at ageing in a new light: they aren’t merely dallying with the affectations of youth, they’re staying loyal to the tenets of a youth culture – a look-at-me decadence, a rebel theatre, an idiosyncratic style – that they helped to invent. As Exhibitionism draws attention to them once again, plenty of people will call The Rolling Stones a travesty of their former selves. But really, they’re perpetuating their legend, not debasing it. For if one of their principles is that rock’n’roll is innate, a calling, then it’s necessary for them to be seen to pursue it until the absolute end. They’re the proof that this music refuses to fade away, in spite of how transient it has appeared at times over the past 50 years.

They’re a band that demand analysis – and God knows we’re offering you plenty of that in our Ultimate Music Guide – but simultaneously transcend it: there’s only so much you can intellectualise about something so immediate and, still, exhilarating.

“It’s ‘orrible to be the Grand Old Men,” Jagger told Melody Maker in, yes, 1972. “If all this talk gets any worse I’ll be getting another band…”