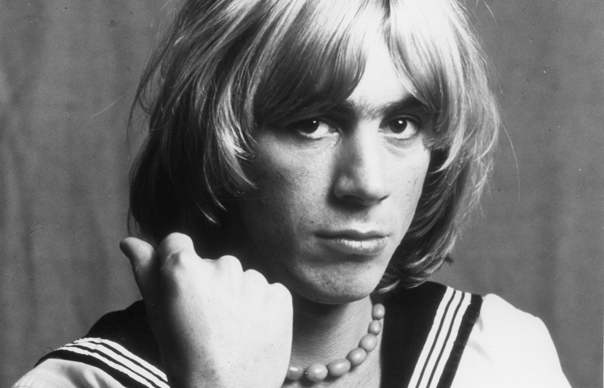

Kevin Ayers, one of Britain’s most gifted and idiosyncratic singer-songwriters, has died at the age of 68. Ayers was born in Kent in 1944. Though he spent his childhood in Malaysia – moving there with his mother and British district officer stepfather – he returned to London at 12, only to be...

Kevin Ayers, one of Britain’s most gifted and idiosyncratic singer-songwriters, has died at the age of 68.

Ayers was born in Kent in 1944. Though he spent his childhood in Malaysia – moving there with his mother and British district officer stepfather – he returned to London at 12, only to be told to leave the city by a magistrate five years later following a drug bust. Ayers always maintained the bust that sent him into exile (and more importantly, into Canterbury) was a set-up. Whether it was or wasn’t, it was certainly an act of fate.

In Canterbury, Ayers joined forces with Brian and Hugh Hopper, Robert Wyatt and Mike Ratledge forming a tight-knit pack of well to do schoolboys. Ayers formed a band with the more worldly Daevid Allen, who had worked with William Burroughs and minimalist composer Terry Riley, and who was renting a room in Canterbury from Wyatt’s mom.

After a short stint as The Wilde Flowers, the band – now Ayers, Wyatt, Ratledge and Allen – eventually took a new name from Burroughs’ The Soft Machine, and became one of the most potent forces on the emerging London psychedelic scene. Ayers played bass (later, guitar, after Allen’s departure) and sang many of the group’s songs, in a baritone that at once conveyed a wry delight in the world around him and a certain lugubriousness that transcended his age. Close competitors with The Pink Floyd, Soft Machine’s debut single “Love Makes Sweet Music” was released in February 1967, a month ahead of the Floyd’s “Arnold Layne”, while in 1970, Syd Barrett appeared on a long-unreleased version of Ayers’ “Religious Experience (Singing A Song In The Morning)”.

Ayers only lasted in Soft Machine long enough to appear on their debut self-titled album (1968), notably contributing the exploratory band’s poppiest song, “”Why Are We Sleeping?” A restless and single-minded artist, Ayers left after a fraught tour with Jimi Hendrix and retreated to Ibiza.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oaxPJ_V3kvE

Iziba brought out the best in Ayers’ songwriting. He parlayed a spate of new songs into his fine solo debut, Joy Of A Toy (1969), that initiated a series of wonderful albums for the Harvest label. Shooting At The Moon (featuring a new band, The Whole World, anchored by David Bedford and featuring a teenage Mike Oldfield), Whatevershebringswesing and Bananamour showcased Ayers as a romantic, sometimes rather louche bon viveur, forging a capricious path through an evolving late ‘60s and early ‘70s scene. His music was quintessentially English, always charming and often whimsical, but Ayers also had an unusually continental bent; he spent his later years in the south of France.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a6kslKx5Zdo

Commercial success generally proved to be just out of his reach, but Ayers’ albums continued to bewitch a devout band of fans. Perennially well-connected, he worked with Eno and Nico, slept with John Cale’s wife (Cale’s “Guts” is about Ayers) and mentored at least one guitar prodigy in Oldfield.

Towards the end of the decade, however, Ayers’ music suffered, and addiction further complicated an erratic career path through the ‘80s and ‘90s. After a 15-year hiatus, Ayers returned in 2007 with The Unfairground, a dazzling return to form that showcased his apparently languid brilliance while featuring contributions from old friends like Wyatt and Phil Manzanera. A younger generation of musicians, from bands like Teenage Fanclub, The Ladybug Transistor and Gorky’s Zygotic Mynci, also helped out, revealing that Ayers’ gentle take on psychedelia had proved covertly influential over the years.

The Unfairground proved to be Ayers’ last release, “largely concerned,” wrote Uncut’s Andy Gill, “with the passage of time, its songs reflecting lost loves, wrong turnings and missed opportunities. Which isn’t to say it’s in any way downbeat or depressing in tone: there’s an equanimity about the past that does Ayers credit, and may be due in part to the relaxed Mediterranean lifestyle he’s pursued for the past three decades…

“Ayers’ amenability shines through regardless, a wave of warmth that can lighten the heaviest soul”.

You can read Uncut’s Album By Album feature with Kevin here.