In an age when the commercial imperative has reduced the notion of ideal musical production to one of recycling old techno riffs, slapping a treated "cartoon" voice on top and flogging them as kiddywinks' ringtones, it takes a breathtaking leap of aesthetic faith to undertake a project like Sufjan Stevens' 50 States. Not even Yes or Magma at their most hubristic could match the ambition of Stevens' conception: a song-cycle of 50 albums, each concerning an individual American state - well, maybe 49 and an EP for Rhode Island. It isn’t just a succession of limp travelogues and familiar town songs like "Sweet Home Chicago", either. Stevens’ albums are idiosyncratic collections of mini-operettas, musings upon historical figures and legends, evocations of architecture, skylines and landscapes, ruminations upon localised industrial development, and even more arcane matters whose pertinence is not immediately obvious. All rendered in a weird, pan-stylistic blend of alt.country, minimalism and American brass band music, as if John Philip Sousa, Steve Reich and Bonnie “Prince” Billy had together stumbled across the clippings-file of some mid-west small-town newspaper and decided to set it to music. And then, just for good measure, given titles to the individual tracks which read like bogus headlines from The Onion: "Prairie Fire That Wanders About"; "The Predatory Wasp Of The Palisades Is Out To Get Us"; and my favourite, "To The Workers Of The Rock River Valley Region, I Have An Idea Concerning Your Predicament, And It Involves An Inner Tube, Bath Mats, And 21 Able-Bodied Men". Try fitting that on your bloody mobile, Crazy fucking Frog! Stevens started the project with his third album, 2003's Michigan, taking the easy way in with his home state. And now, after a personal detour for last year’s Seven Swans set and diligent researching of the relevant atlases, almanacs and biographies, Michigan's neighbour Illinois. A key track in establishing the general tone is "Come On! Feel The Illinoise!", whose punning title hides a rumbustious blend of piano, percussion and horns bustling along at some quirky tempo, with Stevens coming across like Ben Folds with a typically tricksy lyric that both celebrates and questions the notion of progress: "All great intentions/Get covered with the imitations/Have you no conscience?/Oh god of progress/Have you degraded or forgot us?". With a fusion-style keyboards solo, and a few streaks of violin shading the later stages, it recalls '60s Canterbury Sound bands such as Caravan, only more industriously energetic - as perhaps befits its subject. Individual towns are treated in a variety of ways. With a gentle piano and strings intro giving way to shambling banjo and guitar, "Jacksonville" is a heart-warming statement of faith in small-town cosiness: "I've seen things that are meant to save/The bandstand chairs, and the Dewey Day Parade/I go out to the Golden H/The spirit is right, and the spirit doesn't change". Set to lolloping banjo, guitar and accordion, "Decatur, Or, Round of Applause for Your Step-Mother!" mainly provides an opportunity to nonsense-rhyme the location with terms like alligator, hate her, data and aviator, as in a children's nursery-rhyme, ultimately establishing that "Abraham Lincoln was the great emancipator" before concluding in round form with a series of staggered line-repetitions. On Michigan, Detroit's former industrial glories were the subject of celebration and eulogy. "Chicago", by contrast, is a much more personal piece, Stevens recalling romantic stays in that city, and subsequently his current home of New York, that helped him grow as a person: "I was in love with the place/In my mind/I made a lot of mistakes/In my mind". The only industry here is all in the arrangement, the youthful optimism summed up in the massed chorus and strings chugging eagerly along like a train. Here and in several other tracks, such as the aforementioned "Prairie Fire. . .", there's something of the anachronistic grandeur of The Polyphonic Spree about Stevens' musical vision. Elsewhere, more muted settings are appropriate, as in the brief, wistful piano and trumpet instrumental offered "To The Workers Of The Rock River Valley Region. . .", or the simple guitar and banjo that accompany Stevens' reminiscence of a prim bible-study-class romance in "Casimir Pulaski Day", with suitably upright horns lending dignity to the coda. In its evocation of lost innocence, and affectionate old-tyme musical texture, it recalls one of Van Dyke Parks' charming faux-historical curios. Less happily remembered is "John Wayne Gacy, Jr.", the serial killer's legend recounted over delicate piano and guitar. "His neighbours they adored him for his humour and his conversation/Look underneath the house there, find the few living things rotting fast in their sleep of the dead," sings Stevens, his hushed whisper shifting into pained falsetto as he recalls Gacy's victims, before considering his own secret shame: "But in my best behaviour, I am really just like him/Look beneath the floorboards for the secrets I have hid." Stevens manages to maintain a sort of mottled musical consistency throughout, applying his various tones, timbres and textures in the manner of an abstract painter, so that a splash of crunching rock guitar in "The Man Of Metropolis Steals Our Hearts" is balanced six tracks away by the mournful piano and spooky lowing of "The Seer's Tower", and the fluttering woodwind and declamatory choral chords of the Native American massacre elegy "The Black Hawk War. . ." (full title too long to include here) by the sparkling vibes and descending horn runs of "The Tallest Man, The Broadest Shoulders" - without there being any apparent disjunction between the various parts. Rather, they combine as elements in a much larger overall picture, threaded together by the recurrent see-sawing minimalist orchestrations that feature in several tracks, culminating in the untitled bonus track that concludes the proceedings like a potted four-minute precis of Steve Reich's Music For 18 Musicians, its reeds, piano, tuned percussion and vocal sussurus shuffling daintily in and out of sync. Illinois is an extraordinary achievement, all the more so when one considers that besides researching and writing the album, Stevens also played most of the parts himself. And if he can be so inspired by a relatively unremarkable state such as this, just imagine what awaits us when he reaches places like Tennessee, Louisiana and California. . . By Andy Gill

In an age when the commercial imperative has reduced the notion of ideal musical production to one of recycling old techno riffs, slapping a treated “cartoon” voice on top and flogging them as kiddywinks’ ringtones, it takes a breathtaking leap of aesthetic faith to undertake a project like Sufjan Stevens’ 50 States.

Not even Yes or Magma at their most hubristic could match the ambition of Stevens’ conception: a song-cycle of 50 albums, each concerning an individual American state – well, maybe 49 and an EP for Rhode Island. It isn’t just a succession of limp travelogues and familiar town songs like “Sweet Home Chicago”, either. Stevens’ albums are idiosyncratic collections of mini-operettas, musings upon historical figures and legends, evocations of architecture, skylines and landscapes, ruminations upon localised industrial development, and even more arcane matters whose pertinence is not immediately obvious. All rendered in a weird, pan-stylistic blend of alt.country, minimalism and American brass band music, as if John Philip Sousa, Steve Reich and Bonnie “Prince” Billy had together stumbled across the clippings-file of some mid-west small-town newspaper and decided to set it to music. And then, just for good measure, given titles to the individual tracks which read like bogus headlines from The Onion: “Prairie Fire That Wanders About”; “The Predatory Wasp Of The Palisades Is Out To Get Us”; and my favourite, “To The Workers Of The Rock River Valley Region, I Have An Idea Concerning Your Predicament, And It Involves An Inner Tube, Bath Mats, And 21 Able-Bodied Men”. Try fitting that on your bloody mobile, Crazy fucking Frog!

Stevens started the project with his third album, 2003’s Michigan, taking the easy way in with his home state. And now, after a personal detour for last year’s Seven Swans set and diligent researching of the relevant atlases, almanacs and biographies, Michigan’s neighbour Illinois. A key track in establishing the general tone is “Come On! Feel The Illinoise!”, whose punning title hides a rumbustious blend of piano, percussion and horns bustling along at some quirky tempo, with Stevens coming across like Ben Folds with a typically tricksy lyric that both celebrates and questions the notion of progress: “All great intentions/Get covered with the imitations/Have you no conscience?/Oh god of progress/Have you degraded or forgot us?”. With a fusion-style keyboards solo, and a few streaks of violin shading the later stages, it recalls ’60s Canterbury Sound bands such as Caravan, only more industriously energetic – as perhaps befits its subject.

Individual towns are treated in a variety of ways. With a gentle piano and strings intro giving way to shambling banjo and guitar, “Jacksonville” is a heart-warming statement of faith in small-town cosiness: “I’ve seen things that are meant to save/The bandstand chairs, and the Dewey Day Parade/I go out to the Golden H/The spirit is right, and the spirit doesn’t change”. Set to lolloping banjo, guitar and accordion, “Decatur, Or, Round of Applause for Your Step-Mother!” mainly provides an opportunity to nonsense-rhyme the location with terms like alligator, hate her, data and aviator, as in a children’s nursery-rhyme, ultimately establishing that “Abraham Lincoln was the great emancipator” before concluding in round form with a series of staggered line-repetitions.

On Michigan, Detroit’s former industrial glories were the subject of celebration and eulogy. “Chicago”, by contrast, is a much more personal piece, Stevens recalling romantic stays in that city, and subsequently his current home of New York, that helped him grow as a person: “I was in love with the place/In my mind/I made a lot of mistakes/In my mind”. The only industry here is all in the arrangement, the youthful optimism summed up in the massed chorus and strings chugging eagerly along like a train.

Here and in several other tracks, such as the aforementioned “Prairie Fire. . .”, there’s something of the anachronistic grandeur of The Polyphonic Spree about Stevens’ musical vision. Elsewhere, more muted settings are appropriate, as in the brief, wistful piano and trumpet instrumental offered “To The Workers Of The Rock River Valley Region. . .”, or the simple guitar and banjo that accompany Stevens’ reminiscence of a prim bible-study-class romance in “Casimir Pulaski Day”, with suitably upright horns lending dignity to the coda. In its evocation of lost innocence, and affectionate old-tyme musical texture, it recalls one of Van Dyke Parks’ charming faux-historical curios.

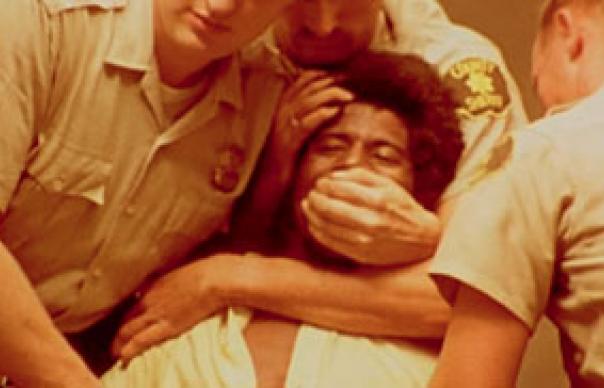

Less happily remembered is “John Wayne Gacy, Jr.”, the serial killer’s legend recounted over delicate piano and guitar. “His neighbours they adored him for his humour and his conversation/Look underneath the house there, find the few living things rotting fast in their sleep of the dead,” sings Stevens, his hushed whisper shifting into pained falsetto as he recalls Gacy’s victims, before considering his own secret shame: “But in my best behaviour, I am really just like him/Look beneath the floorboards for the secrets I have hid.”

Stevens manages to maintain a sort of mottled musical consistency throughout, applying his various tones, timbres and textures in the manner of an abstract painter, so that a splash of crunching rock guitar in “The Man Of Metropolis Steals Our Hearts” is balanced six tracks away by the mournful piano and spooky lowing of “The Seer’s Tower”, and the fluttering woodwind and declamatory choral chords of the Native American massacre elegy “The Black Hawk War. . .” (full title too long to include here) by the sparkling vibes and descending horn runs of “The Tallest Man, The Broadest Shoulders” – without there being any apparent disjunction between the various parts. Rather, they combine as elements in a much larger overall picture, threaded together by the recurrent see-sawing minimalist orchestrations that feature in several tracks, culminating in the untitled bonus track that concludes the proceedings like a potted four-minute precis of Steve Reich’s Music For 18 Musicians, its reeds, piano, tuned percussion and vocal sussurus shuffling daintily in and out of sync.

Illinois is an extraordinary achievement, all the more so when one considers that besides researching and writing the album, Stevens also played most of the parts himself. And if he can be so inspired by a relatively unremarkable state such as this, just imagine what awaits us when he reaches places like Tennessee, Louisiana and California. . .

By Andy Gill