As the 1980s wound down, REM found themselves in an awkward but promising position. The elliptical jangle that clouded their early records had cleared, to reveal a band with a purpose and directness few could have foreseen. Their first records had marked out REM as part of the upsurge in American underground music alongside the likes of Sonic Youth and Husker Du; albeit with a sound more identifiably rooted in rock tradition. Slowly, though, it became obvious that REM’s ambition – and, critically, their potential for universality – reached far beyond that of their peers. If Peter Buck, Mike Mills and Bill Berry appeared to be modest, courteous artisans, and Michael Stipe a strategically odd art-rocker, they had worked out a way to bring these values to stadium-sized audiences and compete with U2 rather than Miracle Legion. 1987’s 'Document' presented a band ready to make the move from Miles Copeland’s IRS (hardly a homespun indie label, but an indie nevertheless) into the covetous arms of Warner Brothers. It may not have been quite the end of the world as they knew it. But plenty of REM’s fans had reason to worry that their cultish heroes would lose even more of the mystique that had made them so appealing. They did, of course. Diehards may argue that REM never bettered their first three albums. Nevertheless, as they became, for a time, the biggest rock band in the world, they were also riven by an internal war: between brash, muscular, marginally eccentric rock, the music a band of REM’s size felt obliged to make; and subtler, acoustically-driven music which, perversely, brought them their biggest successes. The dichotomy is most glaring on 'Green', their Warners debut released on American election day, 1988. From the opening song, “Pop Song ‘89”, the dilemma is hammered home by Stipe, seemingly unsure now who he wants – or who he’s meant - to be. “Hello, I’m sorry I lost myself,” he sings, caught between superstardom and introversion. Where the band had embraced clarity as early as 'Lifes [NB NO APOSTROPHE] Rich Pageant' in ’86, Stipe was only belatedly bringing his words and opinions into focus. 'Green' was designed as a punchy, uplifting, politically mobilising record and, to that end, songs like “Stand” were clarion calls wedded to goofy pop-rock. Greenpeace stalls stood in the foyers of REM gigs now, and the band sounded precariously liberated, confident enough to transmit less ambiguous messages. The beautiful political allegory “World Leader Pretend” even had its lyrics printed on the album sleeve – a previously unthinkable concession. Still, the songs that resonated most on 'Green' were the anomalies: the brittle mandolin sketches “You Are The Everything”, “Hairshirt” and “The Wrong Child”. As REM became major players, few could have imagined that these were establishing a template for the band’s most auspicious success. That became clearer on 1991’s 'Out Of Time', when “Losing My Religion” outperformed its daft single sibling, “Shiny Happy People”. 'Out Of Time' saw the band trying out new directions: rap-rock (the KRS One-augmented “Radio Song”), exuberant dumb pop (“Shiny Happy People”), and, most propitiously, a way of making their folky digressions and Stipe’s paradoxical relationship with fame into something quietly anthemic (“Losing My Religion”). For all its general lushness, it also feels like a record where Stipe is trying to claw back some of his enigmatic status. The explicit politics were dropped – Stipe’s popularity brought him a platform beyond music to express his opinions – and the singer briefly suggested that the album should be called 'The Return Of Mumbles'. On the outstanding track, a stream-of-consciousness meditation called “Country Feedback”, he happily sublimated himself back into the music. Consequently, Stipe scrupulously avoided interviews throughout the early ‘90s, and misinformed rumours proliferated that he had contracted the HIV virus. To many, 1992’s extraordinary 'Automatic For The People' seemed to confirm them, as the singer contemplated mortality from diverse perspectives. “Try Not To Breathe” even suggested that the singer was musing on suicide, until he belatedly revealed that the song came from the perspective of a geriatric woman drawn to euthanasia. Finally, the album found REM concentrating on their mature strengths: dignity, mandolins, sombre brown textures (with string arrangements by John Paul Jones), unblinking seriousness of intent, giant consolatory hugs in “Everybody Hurts” and “Find The River”. It sold extravagantly – 12 million copies worldwide. But even before its release, REM had resolved to undo its good work and make an all-electric album. 'Monster' (1994), designed to give the band some crude, glammy songs to play on their first world tour in half a decade, was not quite as trashy as its reputation suggests. Its best song, “Let Me In”, was a moving requiem for Kurt Cobain constructed out of feedback played by Mike Mills on one of Cobain’s old guitars. But predominantly, 'Monster' was anti-compassionate, and this time Stipe’s narrators were jealous obsessives – stalkers, even - fixated on sex over spiritual consolation. Momentarily free from being totemic bleeding hearts, REM took to the road. Berry had an aneurysm. Mills collapsed with abdominal pains. Stipe had a hernia. And somehow, they also recorded an album in transit, 'New Adventures In Hi-Fi' (1996). Just before its release, Warners renewed their contract, advancing them $80 million for the next five albums: an outlay which, when 'New Adventures' fell well short of its predecessors’ sales, looked a tad overgenerous. Artistically, though, it proved a triumph. If the previous two albums had isolated the acoustic and electric strands of their make-up, 'New Adventures' mixed them up again. At times – notably on “E-Bow The Letter”, a revisiting of “Country Feedback” featuring Patti Smith - a satisfying murk reappeared around the band, as if by returning to heavy touring the band had closed up again. Soon after, physically spent, Bill Berry quit the band, and the remaining trio ignored their long-held pledge to split should any member leave. Instead, they took the opportunity to rethink how an REM record should sound. “Airportman” begins 'Up' (1998) subversively, with drum machines, vintage synths and Stipe intoning, “Great opportunity awaits”. But while they could change the palette and make their songs sound like pretty, occasionally sinister trinkets, REM were incapable of changing their fundamental nature. And once the more experimental tracks on 'Up' drifted away, the overlong album revealed a band perilously close to a pastiche of their younger selves. 'Reveal' (2001) confirmed as much: on “Disappear”, Stipe ruefully noted, “The crushing force of memory, erasing all I’ve been.” A sunny, lavish production also seemed rather stifling. Nevertheless, some fine songs lurked in this polished environment; “Beachball”, in particular, perfected the heat-hazed Beach Boy reverie the band had been fine-tuning for some years. On last year’s 'Around The Sun', however, the lack of substance was more troubling. Stipe’s return to political engagement had undoubted elegance, but the music which accompanied it – a plush, keyboard-heavy updating of 'Automatic'’s gravitas – mostly lacked the craftsmanship and resonance of this enduring band’s best work. Worst of all, 'Around The Sun' felt calculated and over-anxious, when even through the ‘90s REM were reassuringly contrary, constantly veering away from a sensible career path. Peter Buck once called his band, “The acceptable edge of the unacceptable,” but now they seemed orthodox, conservative, content to play the hits on lucrative tours and blandly recycle them for new material. It took REM 12 years to make a commercially exigent follow-up to 'Automatic For The People'. As they probably would have predicted themselves, it wasn’t worth the wait. By John Mulvey

As the 1980s wound down, REM found themselves in an awkward but promising position. The elliptical jangle that clouded their early records had cleared, to reveal a band with a purpose and directness few could have foreseen. Their first records had marked out REM as part of the upsurge in American underground music alongside the likes of Sonic Youth and Husker Du; albeit with a sound more identifiably rooted in rock tradition.

Slowly, though, it became obvious that REM’s ambition – and, critically, their potential for universality – reached far beyond that of their peers. If Peter Buck, Mike Mills and Bill Berry appeared to be modest, courteous artisans, and Michael Stipe a strategically odd art-rocker, they had worked out a way to bring these values to stadium-sized audiences and compete with U2 rather than Miracle Legion. 1987’s ‘Document’ presented a band ready to make the move from Miles Copeland’s IRS (hardly a homespun indie label, but an indie nevertheless) into the covetous arms of Warner Brothers. It may not have been quite the end of the world as they knew it. But plenty of REM’s fans had reason to worry that their cultish heroes would lose even more of the mystique that had made them so appealing.

They did, of course. Diehards may argue that REM never bettered their first three albums. Nevertheless, as they became, for a time, the biggest rock band in the world, they were also riven by an internal war: between brash, muscular, marginally eccentric rock, the music a band of REM’s size felt obliged to make; and subtler, acoustically-driven music which, perversely, brought them their biggest successes.

The dichotomy is most glaring on ‘Green’, their Warners debut released on American election day, 1988. From the opening song, “Pop Song ‘89”, the dilemma is hammered home by Stipe, seemingly unsure now who he wants – or who he’s meant – to be. “Hello, I’m sorry I lost myself,” he sings, caught between superstardom and introversion.

Where the band had embraced clarity as early as ‘Lifes [NB NO APOSTROPHE] Rich Pageant’ in ’86, Stipe was only belatedly bringing his words and opinions into focus. ‘Green’ was designed as a punchy, uplifting, politically mobilising record and, to that end, songs like “Stand” were clarion calls wedded to goofy pop-rock. Greenpeace stalls stood in the foyers of REM gigs now, and the band sounded precariously liberated, confident enough to transmit less ambiguous messages. The beautiful political allegory “World Leader Pretend” even had its lyrics printed on the album sleeve – a previously unthinkable concession. Still, the songs that resonated most on ‘Green’ were the anomalies: the brittle mandolin sketches “You Are The Everything”, “Hairshirt” and “The Wrong Child”. As REM became major players, few could have imagined that these were establishing a template for the band’s most auspicious success.

That became clearer on 1991’s ‘Out Of Time’, when “Losing My Religion” outperformed its daft single sibling, “Shiny Happy People”. ‘Out Of Time’ saw the band trying out new directions: rap-rock (the KRS One-augmented “Radio Song”), exuberant dumb pop (“Shiny Happy People”), and, most propitiously, a way of making their folky digressions and Stipe’s paradoxical relationship with fame into something quietly anthemic (“Losing My Religion”). For all its general lushness, it also feels like a record where Stipe is trying to claw back some of his enigmatic status. The explicit politics were dropped – Stipe’s popularity brought him a platform beyond music to express his opinions – and the singer briefly suggested that the album should be called ‘The Return Of Mumbles’. On the outstanding track, a stream-of-consciousness meditation called “Country Feedback”, he happily sublimated himself back into the music.

Consequently, Stipe scrupulously avoided interviews throughout the early ‘90s, and misinformed rumours proliferated that he had contracted the HIV virus. To many, 1992’s extraordinary ‘Automatic For The People’ seemed to confirm them, as the singer contemplated mortality from diverse perspectives. “Try Not To Breathe” even suggested that the singer was musing on suicide, until he belatedly revealed that the song came from the perspective of a geriatric woman drawn to euthanasia. Finally, the album found REM concentrating on their mature strengths: dignity, mandolins, sombre brown textures (with string arrangements by John Paul Jones), unblinking seriousness of intent, giant consolatory hugs in “Everybody Hurts” and “Find The River”.

It sold extravagantly – 12 million copies worldwide. But even before its release, REM had resolved to undo its good work and make an all-electric album. ‘Monster’ (1994), designed to give the band some crude, glammy songs to play on their first world tour in half a decade, was not quite as trashy as its reputation suggests. Its best song, “Let Me In”, was a moving requiem for Kurt Cobain constructed out of feedback played by Mike Mills on one of Cobain’s old guitars. But predominantly, ‘Monster’ was anti-compassionate, and this time Stipe’s narrators were jealous obsessives – stalkers, even – fixated on sex over spiritual consolation.

Momentarily free from being totemic bleeding hearts, REM took to the road. Berry had an aneurysm. Mills collapsed with abdominal pains. Stipe had a hernia. And somehow, they also recorded an album in transit, ‘New Adventures In Hi-Fi’ (1996). Just before its release, Warners renewed their contract, advancing them $80 million for the next five albums: an outlay which, when ‘New Adventures’ fell well short of its predecessors’ sales, looked a tad overgenerous. Artistically, though, it proved a triumph. If the previous two albums had isolated the acoustic and electric strands of their make-up, ‘New Adventures’ mixed them up again. At times – notably on “E-Bow The Letter”, a revisiting of “Country Feedback” featuring Patti Smith – a satisfying murk reappeared around the band, as if by returning to heavy touring the band had closed up again.

Soon after, physically spent, Bill Berry quit the band, and the remaining trio ignored their long-held pledge to split should any member leave. Instead, they took the opportunity to rethink how an REM record should sound. “Airportman” begins ‘Up’ (1998) subversively, with drum machines, vintage synths and Stipe intoning, “Great opportunity awaits”. But while they could change the palette and make their songs sound like pretty, occasionally sinister trinkets, REM were incapable of changing their fundamental nature. And once the more experimental tracks on ‘Up’ drifted away, the overlong album revealed a band perilously close to a pastiche of their younger selves.

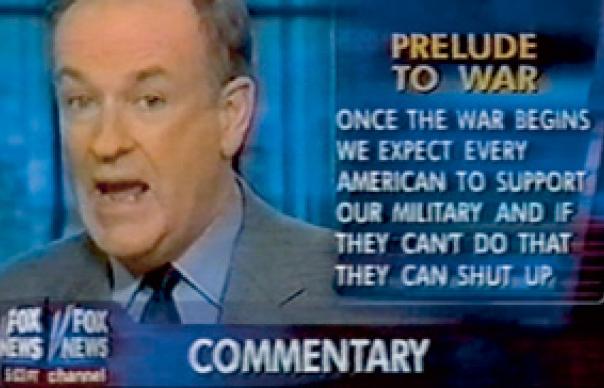

‘Reveal’ (2001) confirmed as much: on “Disappear”, Stipe ruefully noted, “The crushing force of memory, erasing all I’ve been.” A sunny, lavish production also seemed rather stifling. Nevertheless, some fine songs lurked in this polished environment; “Beachball”, in particular, perfected the heat-hazed Beach Boy reverie the band had been fine-tuning for some years. On last year’s ‘Around The Sun’, however, the lack of substance was more troubling. Stipe’s return to political engagement had undoubted elegance, but the music which accompanied it – a plush, keyboard-heavy updating of ‘Automatic’’s gravitas – mostly lacked the craftsmanship and resonance of this enduring band’s best work.

Worst of all, ‘Around The Sun’ felt calculated and over-anxious, when even through the ‘90s REM were reassuringly contrary, constantly veering away from a sensible career path. Peter Buck once called his band, “The acceptable edge of the unacceptable,” but now they seemed orthodox, conservative, content to play the hits on lucrative tours and blandly recycle them for new material. It took REM 12 years to make a commercially exigent follow-up to ‘Automatic For The People’. As they probably would have predicted themselves, it wasn’t worth the wait.

By John Mulvey