For a man who has apparently spent 37 years traumatised by 'Smile', Brian Wilson certainly capitalised on its notoriety in 2004. The past year has seen this elusive ghost-record, beloved of rock mythographers, transformed into a cultural blockbuster. First, the extraordinary shows. Then, the album: rock's great unfinished work resurrected as rock's greatest, unlikeliest salvage job. And now, perhaps inevitably, the movie: 'Beautiful Dreamer', which tells the story of 'Smile' from its beginning - in the tents, sandpits and expanded minds of mid-'60s LA - through to its unveiling, in February 2004, at London's Royal Festival Hall. It's a tremendous yarn, and one which writer/director David Leaf - a long-time Wilson associate and Beach Boys scholar - is eminently qualified to tell. Valuably, the testimony of insiders like David Anderle show how events that have long been used to illustrate Wilson's madness, were actually silly pranks encouraged by the community of freaks around him. The tent in the front room was either for "eating sandwiches" (Wilson) or smoking dope (everyone else). Wilson, incidentally, is a lot funnier and more alert than those who have him pegged as a zombie would have you believe. 'Beautiful Dreamer' is good at this sort of detail, and good at contextualising 'Smile' as a celebration of an idealised America, a means of escaping reality as the country tore itself to pieces over Vietnam. Unfortunately, the army of illustrious talking heads - Burt Bacharach, Jim Webb, Roger Daltrey and more - mouth platitudes rather than provide insights. They are, there, too, for the purpose of padding out 'Beautiful Dreamer'. A product of Wilson's own empire (his wife Melinda is credited as Executive Producer), the singer's ongoing feud with his former bandmates ensures that there is no actual film of The Beach Boys in the entire 110 minutes of the movie. When Leaf deploys a magnificent clip of Wilson singing "Surf's Up" on a 1967 Leonard Bernstein TV special, the absence of contemporaneous footage becomes glaring. If it's a hagiography of Wilson, it's also a - justifiable - demonisation of The Beach Boys, who are portrayed as conservative oafs in comparison to the sophisticated circle of Van Dyke Parks, Anderle and co. Drugs didn't contribute to Brian's breakdown and the dumping of 'Smile', his old friends assert, it was the scepticism and meddling of The Beach Boys. When Wilson lists the reasons he abandoned the record, his first is, "Mike [Love] didn't like it." The second half of the movie is substantially less interesting, with Leaf following Wilson and his band as they prepare the live version of 'Smile'. There are occasional insights into Wilson's volatile nature: he spends one vocal rehearsal anxious and silent, and it's commendable that Leaf and Melinda Wilson haven't sought to portray their subject's depression as entirely cured. But too many of the set-ups feel contrived, and the endless eulogies from his current bandmates are better suited to a concert programme than a documentary. Yes, Brian Wilson is a genius. But after nearly two hours of 'Beautiful Dreamer', you long for one dissenter - Mike Love, say - to call him a pretentious fraud, just for the hell of it. John Mulvey

For a man who has apparently spent 37 years traumatised by ‘Smile’, Brian Wilson certainly capitalised on its notoriety in 2004. The past year has seen this elusive ghost-record, beloved of rock mythographers, transformed into a cultural blockbuster. First, the extraordinary shows. Then, the album: rock’s great unfinished work resurrected as rock’s greatest, unlikeliest salvage job. And now, perhaps inevitably, the movie: ‘Beautiful Dreamer’, which tells the story of ‘Smile’ from its beginning – in the tents, sandpits and expanded minds of mid-’60s LA – through to its unveiling, in February 2004, at London’s Royal Festival Hall.

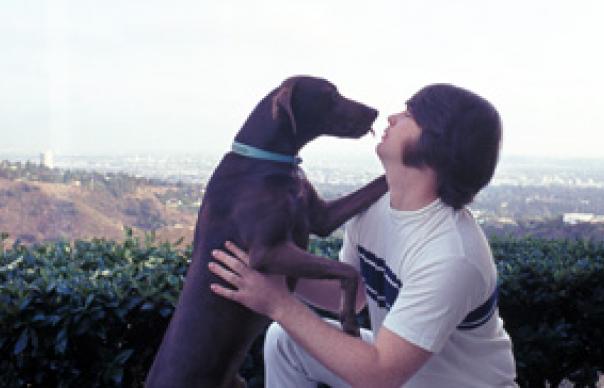

It’s a tremendous yarn, and one which writer/director David Leaf – a long-time Wilson associate and Beach Boys scholar – is eminently qualified to tell. Valuably, the testimony of insiders like David Anderle show how events that have long been used to illustrate Wilson’s madness, were actually silly pranks encouraged by the community of freaks around him. The tent in the front room was either for “eating sandwiches” (Wilson) or smoking dope (everyone else). Wilson, incidentally, is a lot funnier and more alert than those who have him pegged as a zombie would have you believe.

‘Beautiful Dreamer’ is good at this sort of detail, and good at contextualising ‘Smile’ as a celebration of an idealised America, a means of escaping reality as the country tore itself to pieces over Vietnam. Unfortunately, the army of illustrious talking heads – Burt Bacharach, Jim Webb, Roger Daltrey and more – mouth platitudes rather than provide insights. They are, there, too, for the purpose of padding out ‘Beautiful Dreamer’. A product of Wilson’s own empire (his wife Melinda is credited as Executive Producer), the singer’s ongoing feud with his former bandmates ensures that there is no actual film of The Beach Boys in the entire 110 minutes of the movie. When Leaf deploys a magnificent clip of Wilson singing “Surf’s Up” on a 1967 Leonard Bernstein TV special, the absence of contemporaneous footage becomes glaring.

If it’s a hagiography of Wilson, it’s also a – justifiable – demonisation of The Beach Boys, who are portrayed as conservative oafs in comparison to the sophisticated circle of Van Dyke Parks, Anderle and co. Drugs didn’t contribute to Brian’s breakdown and the dumping of ‘Smile’, his old friends assert, it was the scepticism and meddling of The Beach Boys. When Wilson lists the reasons he abandoned the record, his first is, “Mike [Love] didn’t like it.”

The second half of the movie is substantially less interesting, with Leaf following Wilson and his band as they prepare the live version of ‘Smile’. There are occasional insights into Wilson’s volatile nature: he spends one vocal rehearsal anxious and silent, and it’s commendable that Leaf and Melinda Wilson haven’t sought to portray their subject’s depression as entirely cured. But too many of the set-ups feel contrived, and the endless eulogies from his current bandmates are better suited to a concert programme than a documentary. Yes, Brian Wilson is a genius. But after nearly two hours of ‘Beautiful Dreamer’, you long for one dissenter – Mike Love, say – to call him a pretentious fraud, just for the hell of it.

John Mulvey