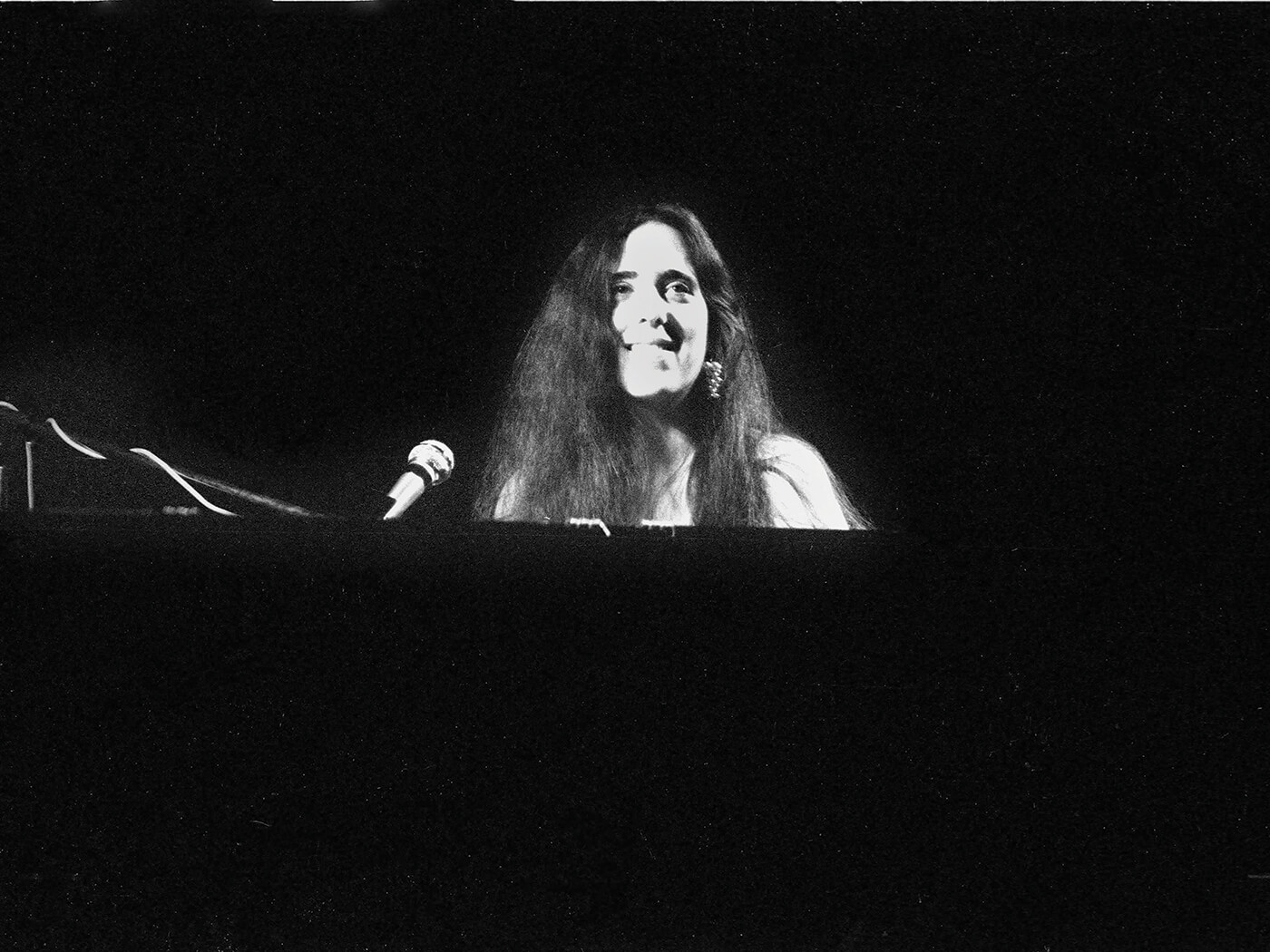

Over the years, Laura Nyro has not been short of admirers. There was David Geffen, of course, who managed her. And Clive Davis, who signed her. Peter, Paul and Mary, Barbra Streisand, and Three Dog Night, who covered her songs. And Bette Midler, who inducted Nyro into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame by noting how “she could make a trip to the grocery store seem like a night at the opera”. But perhaps the definitive compliment came from Alice Cooper, who once described the experience of listening to Nyro’s second album, Eli And The Thirteenth Confession, with awe-struck simplicity: “You sit there and go, ‘That’s songwriting.’”

Nyro was indeed a consummate songwriter. Her extraordinary melding of pop and R&B and jazz and avant-garde piano compositions suggesting a wellspring of musical talent, and a degree of finesse that seemed somehow at odds with her beginnings: the self-taught daughter of a piano-tuner from the Bronx who grew up singing on street corners and subways stations.

Despite her fervent supporters, these days Nyro rarely receives the immediate deference she deserves. Instead, her name bubbles up occasionally – the subject of an anniversary tribute, or as a reference point for other celebrated songwriters (more recent fans have included Kanye West, Jenny Lewis and Tori Amos). In part this is because of the brevity of her life – Nyro died in 1997, aged 49 – and the brevity of her career: signed at 18, by the age of 24, then five albums deep, she had married a carpenter and retreated to rural Massachusetts, far from the grasp of the music industry.

Following her divorce, there were other records – 1976’s Smile and 1978’s Nested, for instance, both included here. Thereafter a gap, motherhood, and a musical re-emergence. But her refusal in later years to promote her music in the customary ways, her tendency to turn down lucrative syncing opportunities, to play predominantly with female musicians, to disseminate animal rights literature at her concerts, meant that in her lifetime she never returned to the mainstream glare.

Still, the music is astonishing. As one early reviewer summed it up: “Laura Nyro is a total experience who explodes on and within you in a way which borders on the mystical”. There was something opulent, perhaps even fragrant, to the way she wrote: the arrangements layered, her voice given to unexpected contortion and richness and texture, so that to listen to her can seem an assault on the senses.

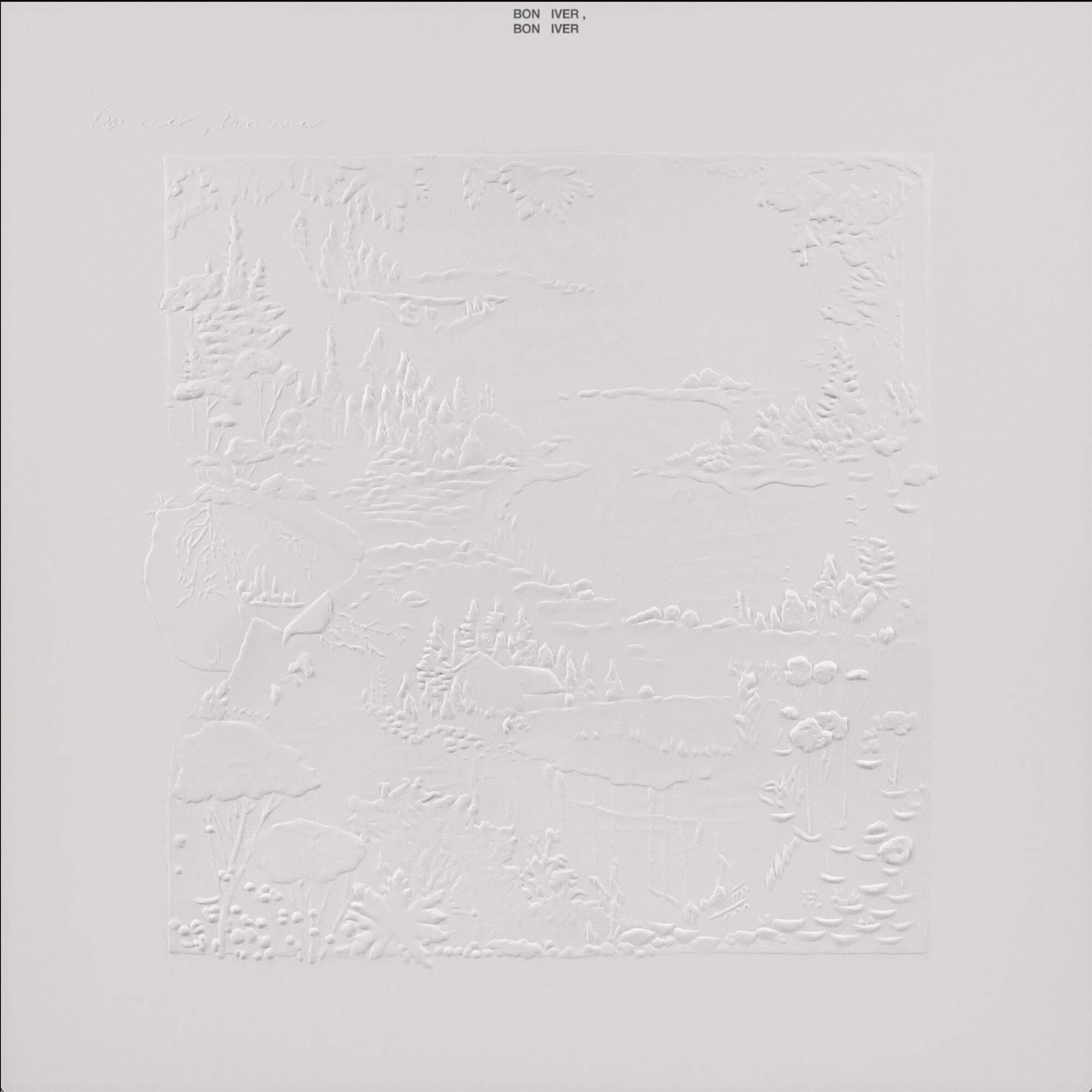

The sheer heft of her talent and her influence is felt in this new boxset: seven studio albums, recorded between 1967 and 1978, all remastered for vinyl, plus a bonus LP of rare demos and live recordings. The accompanying booklet offers interviews, photographs, handwritten lyrics, liner notes by Peter Doggett, and artist testimonials from Elton John to Suzanne Vega, via Graham Nash and Joni Mitchell.

It ranges from the fervent melodies of her debut, More Than A New Discovery, to the mellowed warmth of Nested. Between them lie some of her most-feted records: Cooper’s favourite, Eli And The Thirteenth Confession, released in 1968, is an impassioned and vibrant work, holding some of her most-revered and most-covered songs: Stoned Soul Picnic, Eli’s Comin’ and Sweet Blindness among them.

Gonna Take A Miracle, recorded with the vocal trio Labelle, and produced by Philly soul pioneers Gamble and Huff, offers insight into the music that shaped Nyro’s own songwriting: an album of 1950s and ’60s soul and R&B standards, including Jimmy Mack and Up On The Roof.

New York Tendaberry stands out anew here: striking in its spareness and intimacy, largely pairing just piano with the remarkable smoke and soar of her voice. It’s easy to get distracted by the razzle of single Save The Country (inspired by the assassination of Bobby Kennedy) but it’s in the album’s more muted numbers – the title track,

for instance, and opener You Don’t Love Me When I Cry – that one can see the bones and contours of both her songwriting and her voice. In this she feels like a forerunner to everyone from solo Carole King to James Blake to Alison Moyet.

To listen to this 12-year span of Nyro’s career is to realise how many of her songs are invitations – she is forever encouraging us to ‘go down’ – to picnics, to stoney end, to the grapevine, to the glory river to save the country. To join her. And there is a sadness, somehow, to think of how few responded to that call; for all the accolades and adoration, the highest album spot Nyro would see in her lifetime was No 32 on the Billboard 200.

Posthumous praise, awards and retrospectives might be bittersweet but they bring fresh listeners and new understanding. This boxset – beautiful, thorough, a labour of love, offers an opportunity for many more of us to hear and to reconsider Nyro’s music; to sit there, like Alice Cooper, and go, “That’s songwriting.”