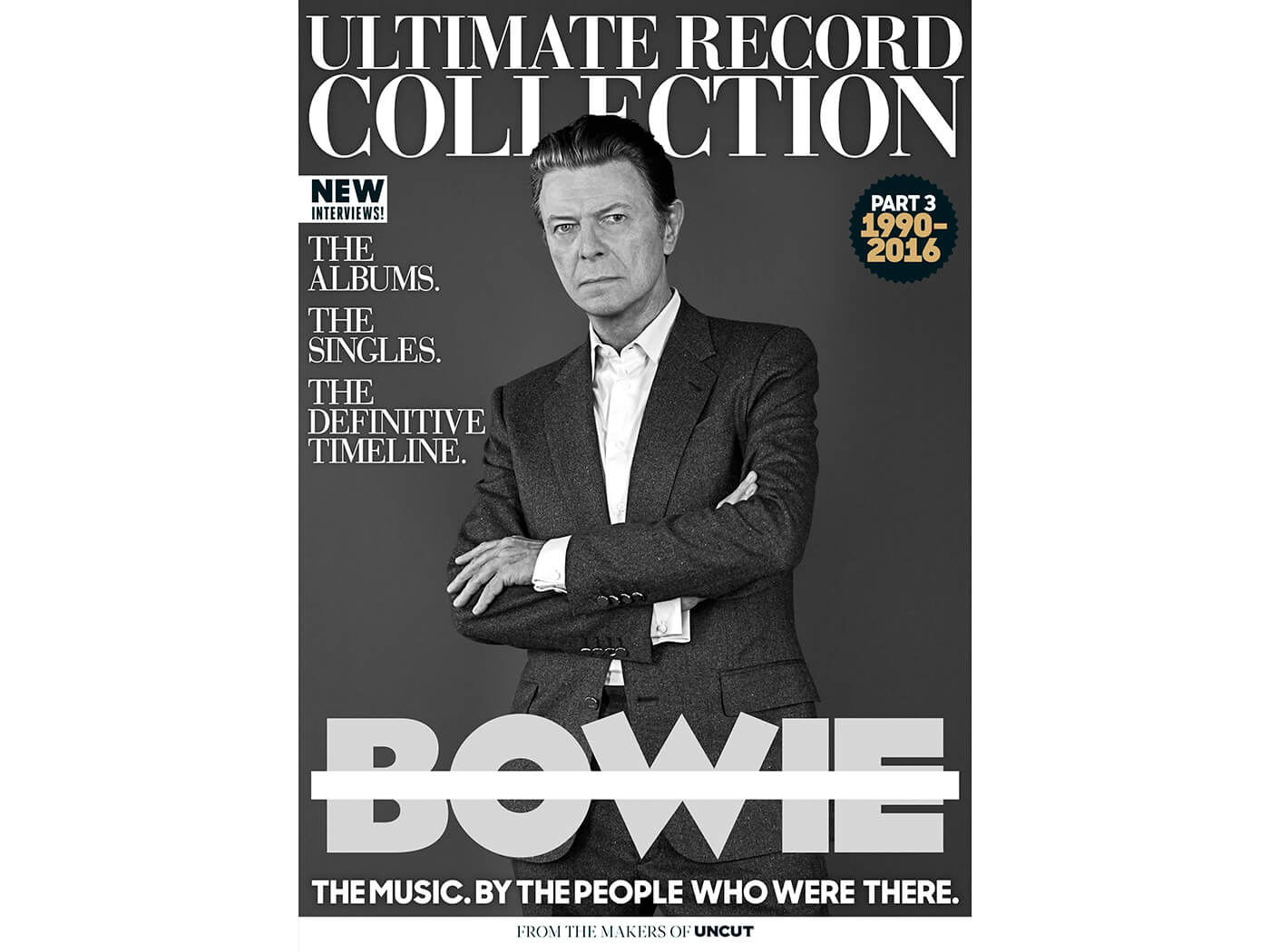

The last part of our Ultimate Record Collection: David Bowie trilogy is here now. Beginning with Bowie’s rediscovery of his past in 1990, and progressing all the way to his final album Blackstar, it’s the definitive timeline of his final decades.

David Bowie – Ultimate Record Collection: Part 3 (1990-2016)

Welcome to Ultimate Record Collection: David Bowie – Part 3 (1990-2016)

BUY THE ULTIMATE RECORD COLLECTION: DAVID BOWIE SERIES HERE

In the two volumes of Ultimate Record Collection: David Bowie so far, we’ve had the pleasure of conducting you through a chronology of the artist’s work – seen through the eyes of the musicians who were there with him making the music.

Through new interviews with early collaborators like Phil Lancaster, Woolf Byrne and Mike Vernon in Part 1, we built an unrivalled oral history of Bowie’s early adventures, and his breakthrough to mature creativity and superstardom. In Part 2 (1977-1989), we uncovered new stories and first-hand accounts about the “Berlin trilogy” and beyond.

Now, as we move to the last decades of Bowie’s lifetime, we find that while some of the personnel remain the same – Mike Garson, one of our most generous interviewees, is often there; Eno returns, as does Tony Visconti, who joins us for some new recollections on Bowie’s later work – Bowie continued to thirst after fresh experience and new directions in his music. We’re particularly privileged to hear from Reeves Gabrels, who can be credited for reminding Bowie that above all, his fans wanted to hear him do exactly what he wanted.

As this volume of Ultimate Record Collection proceeds, it becomes obvious how Bowie’s new music also enjoyed a knowing relationship with his past. This might be obvious on the likes of the VH1 Storytellers album, where Bowie reaches back as far as “Can’t Help Thinking About Me”. Elsewhere though, there’s grounds for thinking that the knowing glances to his earlier self (on the “Buddha Of Suburbia” single, say) ultimately build towards a wonderful circularity.

Designer Jonathan Barnbrook helped develop this self-reference in the brace of sleeve art from The Next Day, an album in which Bowie explicitly referenced his past work. Musically, Bowie’s last works, Blackstar and the Lazarus musical referenced his earliest. He left us much as he found us as an emerging talent in the late 1960s: a musician with a deep affinity for jazz and with an interest in developing some strong ideas for musical theatre. As the artwork of his latest lifetime compilation had it, clearly everything had changed – but at the same time, in the fundamentals of the man’s enthusiasms and passion, nothing had changed at all.

As musical director Henry Hey tells us of Bowie’s work on Lazarus: “I was aware it might be his last project, but I never thought of it like that. Just like he didn’t want his fame to define him when he was working with people, he didn’t want his illness to define him. He was only about positive energy and excitement for the creative process. He would bring this beautiful energy to it.”

Buy a copy of the magazine here. Missed one in the series? Bundles are available at the same location…

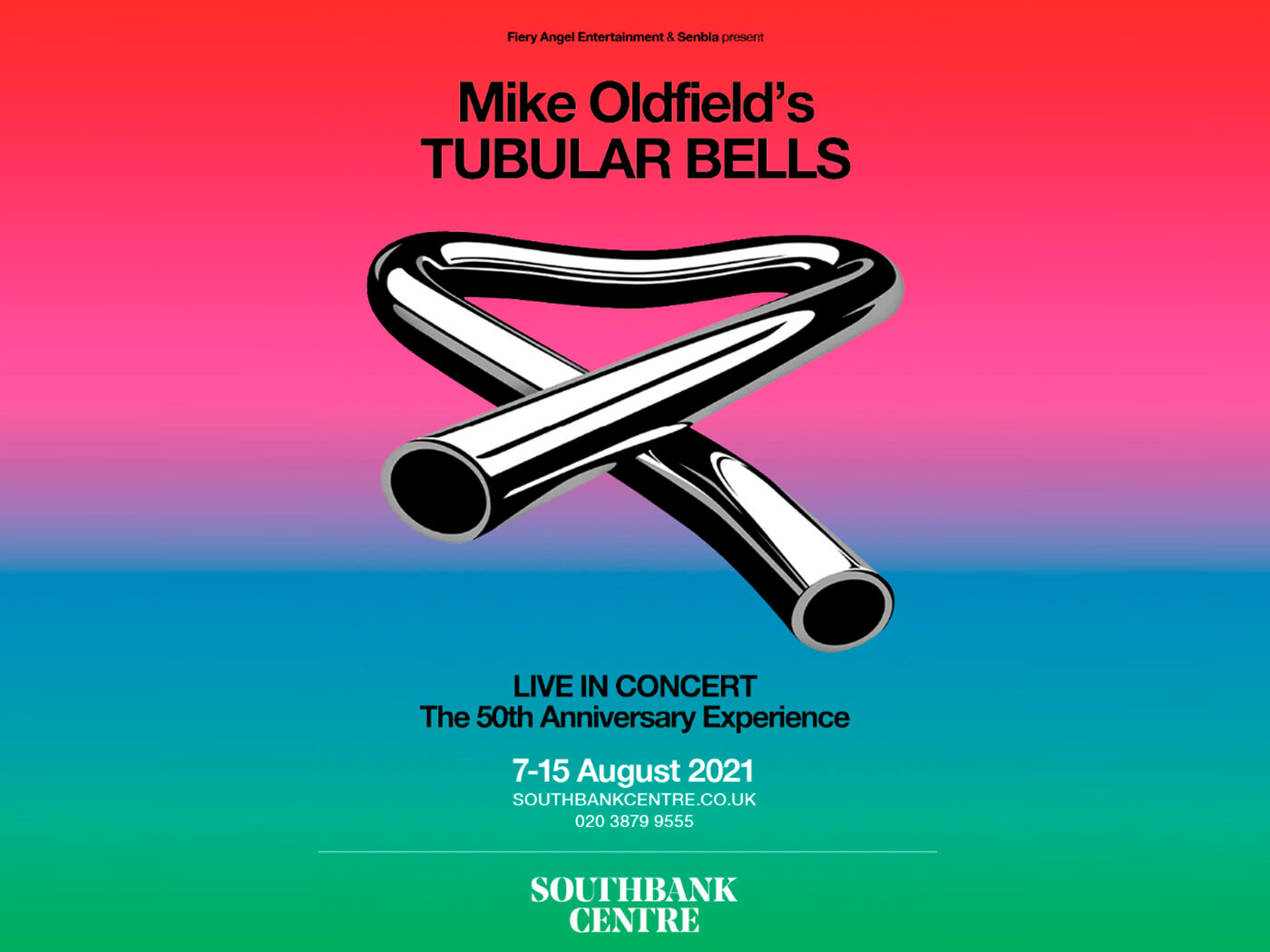

Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells revived for summer concert series

Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells album turns 50 in 2023. Starting the 50th anniversary celebrations early, the album will be performed in an “expansive” live show for nine dates at London’s Royal Festival Hall this August.

Tubular Bells – Live In Concert will feature musical direction from Oldfield’s long-time collaborator Robin A Smith, alongside a visual interpretation by Circa Contemporary Circus led by Artistic Director Yaron Lifschitz, and a new scenic design by William Reynolds.

“It’s amazing to think that it’s 50 years since I started writing Tubular Bells, and I am touched that my music has reached so many people, all over the world, during that time,” says Mike Oldfield. “I have worked with Robin A Smith for almost 30 years, since we presented Tubular Bells together at Edinburgh Castle, through lots of different performances and recordings culminating in the London Olympics in 2012. When I started thinking about reinventing Tubular Bells for live performance with dancers and acrobats—and of course live music, it was Robin who I knew could realise this vision. I am thrilled that this is finally coming to the stage and I trust no-one more to reimagine my work in this way.”

After the Southbank run, the performance will then tour the world until 2023.

Tickets for Tubular Bells – Live In Concert go on general sale here on Friday (January 29) with a pre-sale from Wednesday (January 27). Prices range from £29.50 to £99.50 (plus booking fee).

The Clash in New York: “De Niro took us out clubbing”

The new issue of Uncut – in shops now or available to buy online by clicking here, with no delivery charges for the UK – features an astonishing oral history of The Clash’s 17-date residency at Bond International Casino in New York, during which they caused riots in Times Square, went clubbing with Robert De Niro and kicked off a “punky hip-hop thing” with the city’s newest underground scene. Here’s a little taster:

DON LETTS (DJ/filmmaker): They were like four sticks of dynamite on stage. It was a beautiful thing to see these guys in sync. Off stage there was some friction here and there – a clash of identities, because they were very different people – but on stage it was like the whole Magnificent Seven thing. You do the fucking job. You draw fast, shoot straight and don’t hit the bystanders.

CHRIS SALEWICZ (NME journalist): I hadn’t seen The Clash for some time and I was stunned by their energy on stage. They were really firing, I’d never seen them as good or as powerful. I was there for about nine shows and the whole thing was just steaming. It was all part of how they just took New York. You’d turn on the TV and there’d be Joe and Paul, like some kind of royalty.

JOE ELY (singer-songwriter and guest artist): The sheer power of those shows blew everybody away. Of course the songs were good, but they were showing no mercy. That got around town, which only made the mayhem bigger and louder than it already was. Then there was the social scene that always goes with music events like that. Afterwards everyone would hang out at the Gramercy Park Hotel or another one down on 8th Street. Or the Chelsea Hotel, which was Joe’s favourite because it had so much history.

CHRIS SALEWICZ: There was a bar across the road from Bond’s called Tin Pan Alley, which had been used for one of the scenes in Raging Bull. That became Clash Central for three weeks. Joe and Kosmo [Vinyl, The Clash’s right-hand man] would hang out there. It was run by a lesbian bankrobber, which all added to the weirdness. At one point I remember meeting Robert De Niro and Martin Scorsese, who both thought the whole Bond’s thing was fantastic. That’s how The Clash’s appearance in The King Of Comedy came about. One night, Mick threw a birthday party for [girlfriend] Ellen Foley at Interferon. I remember looking over at Joe and Mick and they just seemed like blood brothers, really tight. They were really enjoying themselves in New York.

DON LETTS: There was a club called Negril that we all used to go to, where Kosmo used to DJ. That’s where we met Rick Rubin, The Beastie Boys, Russell Simmons and Afrika Bambaataa.

PEARL HARBOUR (DJ/singer): The Beastie Boys would be drinking backstage and smoking. They were so young then, just funny guys who were all bowled over by The Clash. John Lydon was a good friend of Paul’s at that time, so he was with us a lot. We’d go to lots of different bars, drinking cocktails we’d never heard of, like Brandy Alexanders – chocolate milkshake with brandy.

PENNIE SMITH (photographer): Everybody popped in all the time, it was mayhem being around The Clash. I remember Scorsese having an oxygen cylinder sitting on the settee. I think he was asthmatic. I took a picture of De Niro talking to Strummer. He was just as much a fan of Joe’s as the other way round. It was a sort of parallel universe.

PEARL HARBOUR: De Niro and Scorsese came out with us a couple of times. Scorsese took us to a really posh Indian restaurant with [then-wife] Isabella Rossellini. When we were all sitting down for dinner, Joe said to Isabella: “Does everybody tell you that you look just like Ingrid Berman?” She said, “Yeah, that’s my mother.” Joe got so embarrassed, because he didn’t know. That was sweet. She and Scorsese thought it was cute. De Niro took us out clubbing one night and also gave us free tickets for a boxing match. He had these fancy $100 seats. I think he just wanted to show us a good time. He became a friend after that. He and Christopher Walken came to visit us in London not long after. We took them out with Joe and Kosmo and all got drunk at Gaz’s Rockin’ Blues. That all happened because of New York.

You can the full story of The Clash’s 1981 Bond Casino shows in the March 2021 issue of Uncut, out now with Leonard Cohen on the cover – buy a copy here!

Genesis reschedule The Last Domino? tour to Autumn 2021

Genesis have been forced to reschedule their upcoming UK and Ireland tour for September and October 2021.

The Last Domino? tour – their first in 14 years – was originally due to take place in 2020 before being postponed to April 2021. Given the ongoing uncertainty surrounding Covid restrictions, it’s now been moved back again. The new dates are as follows:

Wednesday 15th September Dublin 3 Arena

Thursday 16th September Dublin 3 Arena

Saturday 18th September Belfast SSE Arena

Monday 20th September Birmingham Utilita Arena

Tuesday 21st September Birmingham Utilita Arena

Wednesday 22nd September Birmingham Utilita Arena

Friday 24th September Manchester AO Arena

Saturday 25th September Manchester AO Arena

Monday 27th September Leeds First Direct Arena

Tuesday 28th September Leeds First Direct Arena

Thursday 30th September Newcastle Utilita Arena

Friday 1st October Newcastle Utilita Arena

Sunday 3rd October Liverpool M & S Bank Arena

Monday 4th October Liverpool M & S Bank Arena

Thursday 7th October Glasgow The SSE Hydro

Friday 8th October Glasgow The SSE Hydro

Monday 11th October London O2

Tuesday 12th October London O2

Wednesday 13th October London O2

Existing tickets remain valid, and ticket holders will be contacted by their ticket agent. New tickets are available here.

In a joint statement, Tony Banks, Phil Collins and Mike Rutherford said: “Well let’s just forget about that last year and focus on 2021 shall we! We can’t wait to finally get this show on the road, but we feel the decision to move the tour is the best one for those planning on attending and for us as a band and crew. We hope now we can all relax a little more and focus on the music and having a good night.”

Watch a new clip of Genesis rehearsing for the tour below:

“We’re ready, but the world isn’t… yet!”

Genesis are rescheduling their April UK and Irish tour dates for autumn 2021 in light of the ongoing pandemic. ‘The Last Domino?’ Tour 2021 will now start in Dublin on 15th September.https://t.co/PwtNfBhTOE pic.twitter.com/tWA6NE4cmc

— Genesis (@genesis_band) January 22, 2021

Cat Stevens – Mona Bone Jakon/Tea For The Tillerman 50th Anniversary boxsets

By 1970, Cat Stevens had been absent from the charts for three years. Rendered hors de combat by a life-threatening bout of tuberculosis, the time out also offered an opportunity for a major reset. The likes of Leonard Cohen, Joni Mitchell and James Taylor were ushering in the age of the sensitive acoustic troubadour, and to Stevens their songs sounded so much more profound and poetic than the overblown, melodramatic orchestral pop of “I’m Gonna Get Me A Gun” and “Matthew And Son”. As he slowly recovered, a stream of songs in a more reflective folk-rock vein poured out of him.

Released from his old recording contract, Stevens auditioned his new material for Chris Blackwell, who had just signed John Martyn and Nick Drake. The result was Mona Bone Jakon. On its release in April 1970 the album flopped. Yet although five platinum LPs would follow over the next four years, MBJ remains the most compellingly human statement of his career.

Half a century on, the naked intimacy of the songs still sounds fresh and alluring, from the spiritual awakening and self-discovery of “I Think I See The Light” and “Katmandu” via the sardonic denunciation of his old life on “Pop Star”, to the confessional soul-searching of “Trouble” and “Maybe You’re Right”.

The original, glorious album on which dandified pop star was reborn as bedsit poet is augmented in this expanded 50th-anniversary “super deluxe” edition with a new 2020 mix, a disc of stripped-down demos that sound even more introspective than the fully worked album versions, and a further disc of contemporaneous live performances.

When Stevens auditioned for Island he allegedly had a cache of 40 new songs, 11 of which appeared on MBJ. Others were recycled on later albums and there are early concert versions here of several tracks that would make it onto Tea For The Tillerman, plus “Changes IV”, which would surface on 1971’s Teaser And The Firecat. Yet somewhat disappointingly amid the wealth of unreleased demos, there’s only one song – “I Want Some Sun” – that we haven’t heard before. It’s fine enough in its way, an upbeat, countryish romp on which Stevens has never sounded so American. But you can hear why it didn’t fit on the album.

Within a month of the release of Mona Bone Jakon, Stevens was back in the studio recording Tea For The Tillerman. Several of its more pensive songs such as “Father And Son” and “On The Road To Find Out” fitted readily into the MBJ template. But at the same time, his writing was developing in other directions. Songs such as “Wild World”, the title track and “Where Do The Children Play” boasted a greater urgency that reflected his growing certainty in his new-found singer-songwriter persona, like a man who has tried on a new coat, wasn’t sure that it would fit but feels increasingly comfortable in its warm embrace.

Again, we get the original album as heard at the time and in a new remix, plus the recent Yusuf-sings-Cat 2020 updates on the songs recently released as Tea For The Tillerman 2. Then there’s a swathe of live recordings and another disc of demos, this time with two previously unreleased songs, the heartfelt “Can This Be Love?” (which could have been a contender) and the throwaway “It’s So Good” (which has no such pretensions).

There are also half-a-dozen other semi-rarities, all of which were previously released on the 2008 boxset On The Road To Find Out. “If You Want To Sing Out, Sing Out” and “Don’t Be Shy” were written for Hal Ashby’s 1971 coming-of-age movie Harold & Maude after Elton John had dropped out and recommended Stevens as his replacement. “Honey Man” is a sprightly duet with Elton from around the same time. “The Joke” is a surprisingly soulful electric blues with a hippie-friendly lyric about “too many schemers and not enough dreamers”, while the whimsical “I’ve Got A Thing About Seeing My Grandson Grow Old” sounds improbably like something The Incredible String Band might have recorded.

Inevitably, there’s a lot of duplication as two crisp vinyl albums that originally clocked in at around 35 minutes apiece

are expanded over nine audio discs and two Blu-rays, so that we end up with 10 versions of “Lady D’Arbanville”, and 16 of “Wild World”. But maybe you can’t have too much of a good thing. 1970 was Stevens’ annus mirabilis and Mona Bone Jakon and Tea For The Tillerman represent the high tide of his troubadour triumph. As he became a pop star for the second time round, he never sounded so real and true again.

Farmer Dave & The Wizards Of The West – Farmer Dave & The Wizards Of The West

You could get a contact high off “Cave Walls”, the first proper song on the self-titled debut by Farmer Dave & The Wizards Of The West. It opens in a cloud of rumbling guitars, hallucinatory synths and drums mixed to sound thick and gummy. The band flirt with the beat, coming down on either side of it, creating a sense of subtle weightlessness, as though they’re all hovering an inch or two off the ground. “May I be your forever freak”, Farmer Dave sings, projecting a sleepy-stoned charisma as he rambles about kid-sister empresses and sneaks in an Easter-egg shout-out to Led Zeppelin. That’s not a guitar solo, but two players trying to untangle their strings before the song ends in a galaxy of distortion.

It’s a fitting introduction to this oddball group, whose buzzed vibe conceals some truly sharp chops and deep smarts. Farmer Dave Scher has spent most of his career on the side of the stage, his guitars (electric, lap steel, pedal steel) set up well out of the way of whoever he’s supporting. A member of All Night Radio and Beachwood Sparks – two turn-of-the-millennium LA bands that found new ways to play old California music – he revealed his frontman ambitions with his genial 2009 solo debut, Flash Forward To The Good Times, then spent the 2010s touring and recording with Jenny Lewis, Kurt Vile & The Violators, Cass McCombs and Chris Robinson, among others. At some point he even found the time to make good on his nickname by moving to a working farm outside Ojai and studying sacred plant medicine in the Amazon.

Both the Wizards Of The West and their self-titled debut grew out of a recent summer residency at Club Pacific in Venice Beach, where they worked up a solid set of songs before workshopping them on small stages up and down the Golden State. Fortunately, they never got the songs too perfect, and the record has the excitement and spontaneity of a live album, albeit without crowd noise or stage banter. The road-hardened quartet bounce off each other with a chummy jocularity, improvising their way towards some form of enlightenment. It’s a modest, affable, occasionally goofy affair, and therein lie its charms.

The music is, of course, steeped in California rock: the cosmic crunch of the Grateful Dead, the spacey twang of The International Submarine Band, the psychedelic spirituality of Ya Ho Wha 13. But their touchstones are so specific, so left-of-centre, that nothing sounds derivative; the Wizards play in present tense, never past. In fact, California – its landscape, its history, its culture and counterculture – becomes the overarching subject of the album. “Ocean Eyes” sounds like a bittersweet love song to the state, as Scher tenderly trips on the romance of the place and turns in some of his loosey-goosiest vocals. “My, how the canyon glo-o-o-ows”, he sings, supplying his own echo. “We’ll always have Big Sur, baby”, he declares and somehow that farewell sounds heartfelt rather than corny.

Instead of apeing their heroes, the Wizards build on those foundations and put their own spin on West Coast sounds. They experiment with space blues on “Mutant Pill” and campfire singalongs on “Stand & Deliver”. On “Bohannon” they eulogise the late Detroit dance auteur Hamilton Bohannon, best known for the 1976 club hit “Let’s Start The Dance”. He’s an unlikely hero, especially since he refused to follow Motown out to California, but the Wizards sound sincere when they chant “Bohannon forever” over a slow-motion disco beat and what sounds like a very long bong hit. It’s a showcase for drummer Jud Birza, whose subtly complex beats rein in the guitars and allow the band to move fleetly. He drives their closing cover of “Wipe Out”, the 1963 hit by The Surfaris. Birza pushes the song along at a gnarly pace, as though he’s trying to jostle the other band members off their boards. They add zombie vocals and toppling waves of organ, and change the key to make it sound like a modded-out version of the Twilight Zone theme, finally bringing it to an end with a noisy crash.

An unlikely climax to an unpredictable and ingenious album, “Wipe Out” might sound like an afterthought, but the band are obviously having a blast reimagining the familiar surf-rock tune, especially in such close proximity to disco, canyon folk and psych rock. They thrive on such far-flung musical juxtapositions and make their excitement contagious. As the forever freak sings on “Stand & Deliver”, “All the Earth is a-where I run”.

Matthew E White and Lonnie Holley team up for new album

Spacebomb supremo Matthew E White has joined forces with Lonnie Holley for a new “avant-garde southern folk record” entitled Broken Mirror: A Selfie Reflection, due out April 9 on Spacebomb/Jagjaguwar.

Hear a track from it, “This Here Jungle of Moderness/Composition 14”, below:

White recorded the music for Broken Mirror: A Selfie Reflection with a septet of musicians in 2018, as an experiment in “loose, gestural composition” akin to Miles Davis’ On The Corner. After backing Holley at a gig in Richmond, Virginia the following year, White played him some edits from those recordings. Holley quickly pulled out his notebooks and sung complete first takes to music he’d never heard.

Pre-order Broken Mirror: A Selfie Reflection here and check out the full tracklisting below:

1. This Here Jungle of Moderness/Composition 14

2. Broken Mirror (A Selfie Reflection)/Composition 9

3. I Cried Space Dust/Composition 12

4. I’m Not Tripping/Composition 8

5. Get Up! Come Walk with Me/Composition 7

My Life In Music: Courtney Marie Andrews

BOB DYLAN

TELL TALE SIGNS

COLUMBIA, 2008

When I was on tour about four or five years ago, I decided to go deeper into Dylan’s catalogue. There’s so much to uncover. I was working with this producer, Mark Howard; he had a lot of sessions that were outtakes for this record, and I became obsessed. I really like the reflective element of it – these are his nostalgic years where he’s kinda an old wise man reflecting on his life. There was a time when I listened to nothing but this record, and it’s become my favourite Dylan record. I feel like I learn more when an old man or woman is singing a song because you really believe the stories behind their years.

CURTIS MAYFIELD

CURTIS

CURTOM, 1970

This is a recent favourite that the producer for my new record sent me when we were talking about our favourite productions. I fell into the well on this one. The production, the social stances that he takes on the record during that time are still important, the cultural relativism – it’s just so good. And his voice is insane; as a singer it’s probably one of my favourite voices. Also, there’s harp on this record, which is so cool that that happened in 1970. Harp on a funk record, yeah!

LUCINDA WILLIAMS

WORLD WITHOUT TEARS

LOST HIGHWAY, 2003

I’ve listened to Lucinda Williams’ music since I was a kid – she’s a deep, deep inspiration for my own music. I first became attached to Car Wheels On A Gravel Road, which is an all-time favourite as well, but I think in recent years I’ve gravitated to World Without Tears, because of the pain in her voice – it has a mark of this very particular moment in time, it feels like all of these songs were written in a month or something. It evokes a very certain feeling that I just love. I think “Fruits Of My Labor” is one of the best songs ever written by anyone – as a songwriter, it’s a world masterclass in songwriting.

JONI MITCHELL

BLUE

REPRISE, 1971

It almost feels not fair to put this on a list – it should just be on everyone’s. It was the first Joni record I heard, and now that I’m older there are certainly records of hers that resonate more, but honestly, for me this one just beats all. It’s the perfect record song-wise; it has so many classics embedded in there. The vulnerability in her voice… It sounds like she’s about to cry on a lot of these songs. It all sounds so full, but there’s hardly anything happening, just a hand drum under some of these songs. It just goes to show that if it’s a good song it’ll carry the weight.

ARETHA FRANKLIN

I NEVER LOVED A MAN THE WAY I LOVE YOU

ATLANTIC, 1967

I got into this record when I was about seven.

I would sing it in my bedroom and knew every word. I learned to sing by listening to this – first I sang obnoxiously loud to try and match her power, then realised that’s not actually the technique. She’s the greatest singer of all time, and it’s incredible to me that these are one-take cuts in the studio – these are her having a go in one take. Also, her empowerment and the way she chose songs that really fit her is inspiring to me too. I’m forever a fan. I loved those gospel recordings that came out a couple of years back – just so good. She’s on another level.

TOM WAITS

MULE VARIATIONS

ANTI-, 1999

Oh man, I was a Tom Waits naysayer in my early twenties. I just couldn’t get past his voice, even though I usually gravitate to strange voices. Then I heard the song “Take It With Me” from this album, my entire world flipped and I became the biggest Tom Waits fan you could ever meet! This is the perfect balance between his weird experimental stuff and his beautiful ballads, such a cool record. I’ve gone back through all his stuff now and I love his early work, but I’m still a sucker for his later records. I’m a big fan of artists’ demos, so I love [2006 boxset] Orphans especially. There are some gems on there. Poetically, he’s probably my favourite writer.

LINDA RONSTADT

CANCIONES DE MI PADRE

ELEKTRA/ASYLUM, 1987

I didn’t grow up listening to Linda Ronstadt even though we’re both from the same state, Arizona. But people kept drawing comparisons between us a bit, so I started getting into her catalogue. I knew the hits, but I went deeper and came across this record. I love the sound of mariachi music; it makes me feel at home, because growing up in Phoenix people are always blasting mariachi everywhere, down the highway and in backyards. When I hear the sound of it I feel at home, and when I get tired of understanding lyrics and words, I put this on and her voice is so soothing to me. It’s like my zen record!

NEIL YOUNG

HARVEST MOON

REPRISE, 1992

It always surprises me that this record came out in the ’90s – it sounds like it could have been a follow-up to Harvest – but I love the songs, the harmonies are amazing, and just the feeling that this record evokes is really special. My dad is a huge Neil Young fan – he does a mean impersonation, so I grew up hearing Neil a lot. But if your parents like something, you want to buy a punk record instead, so I bought a lot of them before I bought a Neil record and realised he’s just as punk. He’s such a simple writer that it can be hard for it to resonate as a teenager – but once it does, man, there’s no-one else like Neil.

Courtney Marie Andrews appears at AmericanaFest UK, taking place virtually from Jan 26–28. Buy a ticket here!

Beverly Glenn-Copeland announces reissue of Keyboard Fantasies

Beverly Glenn-Copeland has announced the reissue of his cult 1986 album Keyboard Fantasies via Transgressive on April 13.

Originally released on cassette, it was rediscovered in the 2010s by Japanese collector Ryota Masuko, leading to a late-career renaissance for Glenn-Copeland. His career-spanning compilation Transmissions: The Music Of Beverly Glenn-Copeland was one of Uncut’s top archive releases of 2020.

This reissue of Keyboard Fantasies will feature new artwork and liner notes by pop singer Robyn, and marks the first time the album has ever been released on CD; an LP version will also be available. You can pre-order both here – early orders will receive a bonus flexidisc featuring an unreleased live recording of “Old Melody” from 1975.

Watch a new live performance video of “Let Us Dance”, directed by Posy Dixon, below:

Watch a video for Tindersticks’ epic new single

Following their cover of the Television Personalities’ “You’ll Have To Scream Louder”, Tindersticks have released a second single from their upcoming album Distractions, due February 19 on City Slang.

Watch a video for the 11-minute “Man Alone (Can’t Stop The Fadin’)” below:

“This song was always a journey but I wasn’t expecting it to be such a long one,” says Tindersticks’ Stuart Staples. “We made a 6 minute version but it felt like it pulled off and stopped half way to its destination. This was the beginning of a long journey in itself, to find the route needed to complete it – probably the biggest challenge a song or piece of music has given us. It was delicate and slippery right up to the final mix, which lasted a week! For me the song has a strange connection to the drum machine, bass guitar and voice combination of Indignant Desert Birds – mine and Neil’s first band when I was 17. It was important to me that the words of the song were not a coherent narrative, but passing thoughts along the way.”

“Man Alone (Can’t Stop The Fadin’)” can also be found on the excellent CD that comes free with the new issue of Uncut. Inside the magazine you can read a two-page review of Distractions, along with more insight from Stuart Staples – click here for more details on the mag and how to buy it.

Neil Young sets release date for Way Down In The Rust Bucket

Neil Young has confirmed that his live album and film Way Down In The Rust Bucket will be released by Reprise on February 26.

It’s the document of a Crazy Horse live show captured at The Catalyst in Santa Cruz on November 13, 1990, just after the recording of Ragged Glory.

The three-hour set features the live debuts of many songs from that album, as well as “Danger Bird” from 1975’s Zuma. Hear “Country Home” below:

Way Down In the Rust Bucket will be released in numerous formats, including a deluxe edition boxset containing a DVD of the concert, alongside four LPs and two CDs. The DVD contains an additional 13-minute performance of “Cowgirl In The Sand” that doesn’t appear on the vinyl or CD editions. There will also be 4xLP vinyl box set and a 2xCD set. Pre-order here.

Watch a trailer for Way Down In The Rust Bucket and check out the tracklisting below:

1. ‘Country Home’

2. ‘Surfer Joe and Moe the Sleaze’

3. ‘Love to Burn’

4. ‘Days That Used to Be’

5. ‘Bite the Bullet’

6. ‘Cinnamon Girl’

7. ‘Farmer John’

#. ‘Cowgirl In The Sand’ (exclusive to the DVD only)

8. ‘Over and Over’

9. ‘Danger Bird’

10. ‘Don’t Cry No Tears’

11. ‘Sedan Delivery’

12. ‘Roll Another Number (For the Road)’

13. ‘Fuckin’ Up’

14. ‘T-Bone’

15. ‘Homegrown’

16. ‘Mansion on the Hill’

17. ‘Like a Hurricane’

18. ‘Love and Only Love’

19. ‘Cortez the Killer’

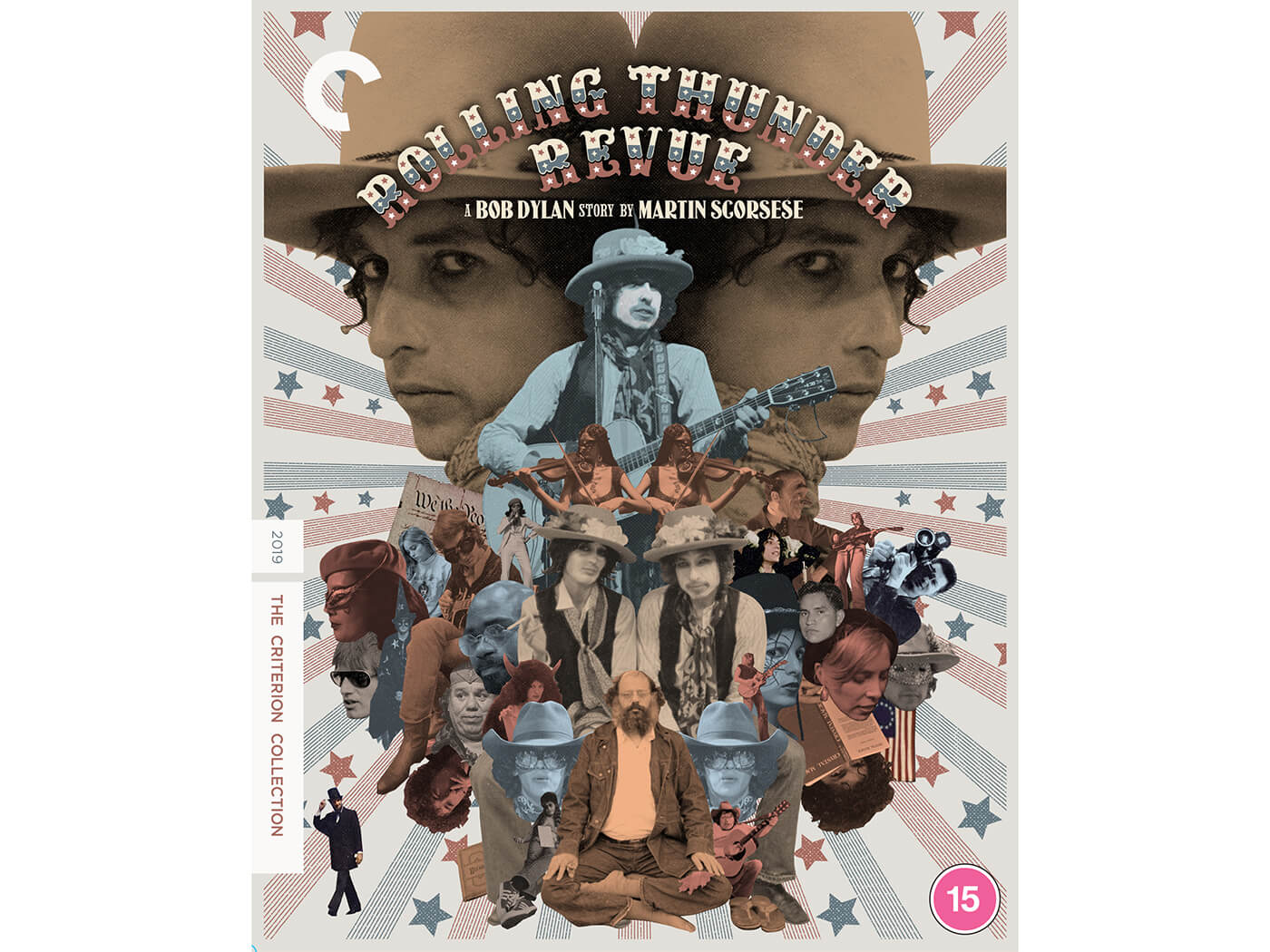

Win a copy of Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story

Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story By Martin Scorsese – the “freewheeling and mischievous” document of Dylan’s legendary 1975/6 tour – is out on DVD and Blu-Ray via Criterion Collection on January 25.

We’ve got 3 copies of the Blu-Ray to give away. All you have do is answer the following question:

Which British guitarist joined Bob Dylan on the Rolling Thunder Revue?

a) Mick Ronson

b) Mick Taylor

c) Mick Jones

Email your answer – along with your name and address – to competitions@www.uncut.co.uk by Monday, January 25. A winner will be chosen by the Uncut team from the correct entries. The editor’s decision is final.

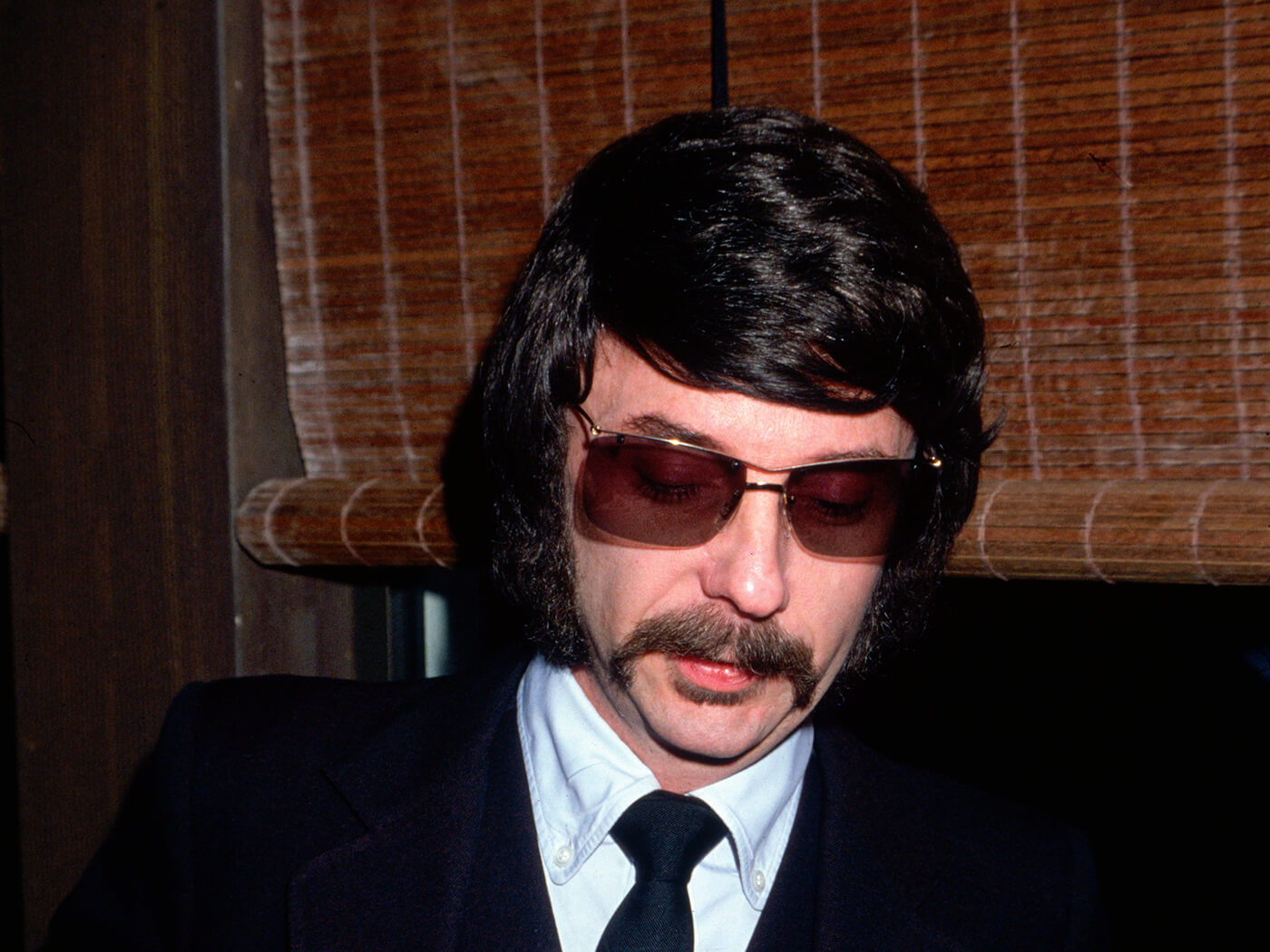

Phil Spector has died, aged 81

Pioneering pop producer Phil Spector has died aged 81, while serving a prison sentence for murder.

The news was confirmed by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, who stated he had died “of natural causes at 6.35pm on Saturday, January 16, 2021, at an outside hospital”. Spector was sentenced to 19 years to life for the murder of Lana Clarkson in 2003.

Spector was still a teenager when his band The Teddy Bears scored a No. 1 hit in 1958 with the self-penned “To Know Him Is to Love Him”. He then restyled himself as a pop svengali, writing and producing a string of hits for the likes of The Crystals, The Ronettes and Ike & Tina Turner, employing his influential ‘wall of sound’ techniques.

After a few years away from the music industry, Spector was hired – controversially – to complete The Beatles’ Let It Be, before working on John Lennon and George Harrison’s subsequent solo albums.

Spector went on to produce sporadically for artists including Leonard Cohen and Ramones, but they took exception to his unpredictable and controlling methods, reportedly bringing guns to the studio to threaten musicians. In 1990, ex-wife Ronnie Spector published a memoir detailing a litany of abusive behaviour towards her.

When Lana Clarkson was found dead of a single gunshot wound at Spector’s California home in 2003, he claimed her death was “accidental suicide”. But Spector was convicted of second degree murder six years later after a retrial.

“It’s a sad day for music and a sad day for me,” wrote Ronnie Spector on Instagram. “The magical music we were able to make together, was inspired by our love. I loved him madly, and gave my heart and soul to him.

“As I said many times while he was alive, he was a brilliant producer, but a lousy husband. Unfortunately Phil was not able to live and function outside of the recording studio. Darkness set in, many lives were damaged.

“I still smile whenever I hear the music we made together, and always will. The music will be forever.”

The Avalanches – We Will Always Love You

If, after suffering hardship, you’ve become particularly attuned to the everyday miracles of earth and sky, awed by the wonder of existence, then you’re already intimate with the hopeful air of We Will Always Love You.

Drenched in mechanised shimmer and kinetic beats, The Avalanches’ third studio effort is at its core a beatific vision born of life’s darker turns, that neither weaponises nor romanticises pain. Instead, We Will Always Love You recognises the arc of pain as one of humanity’s strongest connective tissues, an acknowledgement that doubles as an exorcism, a non-verbal expression that intones, “I feel you, pain, and now I am setting you free.”

Fitting neatly at the junction between curiosity and maturity, the record may disappoint those fans with a particular long-simmering and perhaps unfair desire; it is not the anarchic and astonishing Frankenstein’s monster that was 2000’s Since I Left You or, to a lesser extent, 2016’s Wildflower, not an infinitely layered statement with WhoSampled pages that unravel like Kerouac’s On The Road scroll. It is more pop-oriented and far less mysterious. It is the sound of a group who want more from life than the fetishisation of dusty discs.

Though it retains the same deconstructionist form that made The Avalanches a household name, it does so through a reliance on original collaborations with guest vocalists that are then chopped, refracted and stitched with samples of cult records, obscure historical recordings, warbled YouTube clips and alien frequencies. It’s a less intensive template than Since I Left You, one that fulfils a few practical purposes: less time spent digging and chasing sample clearance, and core members Robbie Chater and Tony Di Blasi’s desire to work in a more standard album-tour cycle, one that doesn’t prompt a 16-year absence between records. In keeping with their liking for concept albums, they’ve crafted a record loosely based on the relationship between ‘science communicators’ Carl Sagan and Ann Druyan, and their ‘love note’ on Voyager’s Golden Record.

Druyan’s face appears on the cover, and she was originally planned to appear on the album; though it didn’t happen, the record is certainly not short of other contributors. While it’s fair to see names like Perry Farrell and Rivers Cuomo and be suspicious, the beauty of We Will Always Love You lies beneath the elder statesmen on the shiny hype sticker. It is here that Karen O whispers some of the last and most profound words written by David Berman, over the crackle of static and a light twinkle of piano (“Pink Champagne”). It is here that pop luminary Dev Hynes meets folk luminaries The Roches and soul legend Smokey Robinson in an elegiac symphony built for headphones (“We Will Always Love You”). It is here that Johnny Marr’s guitar again shimmers with a Smiths-era glimmer (“The Divine Chord”), and a crack modern soul upstart, Cola Boyy, is bolstered by none other than OG sampler Mick Jones (“We Go On”). It is here that a sample of Vashti Bunyan, taken from 1970’s “Glow Worms”, flutters on a wave of psychedelic soul (“Reflecting Light”).

Though sonically We Will Always Love You is unlike the group’s first two albums, its spirit of discovery, and subtle championing of the oblique, forgotten and underrepresented, is familiar territory. The album is neither stuck in the past nor barrelling recklessly towards the future, and, in this sense, it’s a lavish genre-agnostic mixtape. On paper it lacks focus, but in practice it is representative of the aural quilts crafted by modern, omnivorous listeners. Anti-pop sentiment has largely fallen out of vogue among serious music heads, and The Avalanches have long advocated for such progress.

Through its adventuresome twists and well-considered combinations, this record acts as a necessary treat amid a turbulent and uncertain climate; it embraces the promise of love, the wonder of outer realms and the connective quality of music across genres and understanding. A reminder of the energy of bodies at one with a beat, and the soothing quality of a quiet hour alone with one’s thoughts, it’s a hopeful guide to a world where everyone is welcome.

Leonard Cohen: “He charmed the beast”

The new issue of Uncut – in shops now and available to buy online by clicking here – tells the incredible story of Leonard Cohen’s 1970s, as Songs Of Love And Hate ushered in a strange and compelling new era for rock’s pre-eminent poet. There were turbulent tours, intellectual crises, incursions into warzones, lost albums and firearms incidents. Yet as Stephen Troussé discovers, Cohen’s towering genius and remarkable good humour endured. Here’s an extract…

It’s the last weekend of the summer of 1970 and Leonard Cohen arrives in England leading an army. On the face of it, he’s at an all-time high. Songs From A Room, his austere second album, released in April 1969, spent over a month in the higher reaches of the UK Top 10 – only held off the top spot by The Seekers and The Moody Blues. His songs have become unlikely modern standards, covered by everyone from Nina Simone to Fairport Convention. He’s finally making money, too. After a decade scuffling around Europe, living on publishing advances and cadging from friends, he’s now picking up tabs and worrying about real estate.

“I was singing in folk clubs at the time, and I already had two or three of Leonard’s songs in my repertoire,” remembers Jennifer Warnes, an early adopter of Cohen. “‘Dress Rehearsal Rag’ was certainly in there, ‘One of Us Cannot Be Wrong’. His songs had layers of meaning. I was a fan of Brel and Charles Aznavour and Kurt Weill, European art songs, and Leonard seemed to fit right in. It had a little more teeth than the American folk music.”

Finally cajoled into touring by Columbia Records, Cohen had called on the producer of Songs From A Room, the irrepressible Texan maverick Bob Johnston, to play keyboards and round up a band, including Ron Cornelius on guitar and Charlie Daniels on fiddle, to tour the great capitals of Europe.

Johnston saw the tour as a chance to get out of the studio and let his Lone Star spirit out for a canter. Quite literally. Booked to appear in Aix-en-Provence, but finding the road to the festival blocked by a convoy of French hippies, Johnston commandeered a stable of horses for the band to ride through the Provençal fields. Astride a white stallion, dressed in a khaki safari suit and brandishing a whip, Cohen took to the stage and proceeded to lecture the audience, in French, about the competing claims of art and revolution. That night Cohen was the 1970 counterculture world spirit on horseback, fulfilling every Napoleonic dream that the small, studious, ambitious Jewish boy from Westmount, Montreal, had ever had.

But at what cost? On the evening of Friday, August 28, the Army – as Johnston had named the band after the triumph in France – pulled up outside a psychiatric institution in the heart of English commuterland. Henderson Hospital had been founded in 1947 as a trauma unit for shellshocked soldiers struggling to reintegrate back into civilian life after the end of World War II. By 1970, it had become a “democratic therapeutic community”, fostering a communal approach to helping

“outsiders and misfits” who had been failed by conventional approaches to mental distress. A member of the community’s writers group, known only as John, took it upon himself to invite Leonard Cohen to play at the hospital, and seeing an opportunity to warm up for the Isle Of Wight Festival, Cohen graciously accepted.

Cohen felt right at home in Henderson. Playing for over an hour in an attic room in the tower of the hospital, before 50 or so residents and staff, he sounded positively happy. “I really wanted to say that this is the audience we have been looking for,’ he enthused at the end of this set. “I never felt so good before playing before people.”

The show was taped by charge nurse Ian Milne, and the recording now survives in the Planned Environment Therapy Archive in Cheltenham. It finds Cohen in remarkably good humour, drolly detailing the romantic despair and pharmacological derangement that was driving his art. After “You Know Who I Am” he comments, “I don’t know why, but this song seems to have something to do with some 300 acid trips I took.” Meanwhile, he explains, “One Of Us Cannot Be Wrong” was “written in the Chelsea Hotel in New York City. This was written coming off amphetamine. I was also pursuing a woman at the time, an incredibly beautiful singer in a small cafe in the Village and I was completely taken.”

It may not have seemed an obvious preparation for following Jimi Hendrix at the Isle Of Wight Festival, in front of over half a million truculent hippies in a “psychedelic concentration camp”, yet somehow it worked. Still dressed in his safari suit, unshaven and dishevelled, with the Army now referring to him as “Captain Mandrax”, Cohen took to the festival stage at 4am. Kris Kristofferson, who had been booed off a few days previously, was in awe: “He did the damnedest thing you ever saw: he charmed the beast. A lone sorrowful voice did what some of the best rockers in the world had tried for three days and failed.”

He had come and seen and conquered… But now he was “tired of the war/I want the kind of work I had before”, as he wrote in “Joan of Arc”. He very much wanted to go back. Maybe to a cabin in Tennessee or to a whitewashed room by the Aegean Sea, a Zen temple in the San Gabriel Mountains, or just to an attic room in a psychiatric institution in Sutton.

But Cohen’s seven-year tour of duty, his own long season in Hell, was only just beginning. It led him from the devastation of the Isle Of Wight, through the concert halls of Europe and North America, via strange journeys through Israel and Ethiopia, to end up as a “broken-down nightingale”, captive in a holding cell in the Tower Of Song along with Phil Spector.

“Was it a spiritual crisis?” wonders Tony Palmer, another early fan, who watched Cohen at the Isle Of Wight, and later filmed him on the intense 1972 tour of Europe. “It was an intellectual crisis and therefore to an extent an emotional crisis. ‘Why am I doing this?’ he would ask me. I think he was becoming aware, probably for the first time, of the impact both his songs and his performance was having on an audience.”

You can read the full story of Leonard Cohen’s 1970s in the March 2021 issue of Uncut, in shops now or available online here!

The 1st Uncut Playlist Of 2021

I hope you’ve had a chance to pick up our first issue of 2021 – Leonard Cohen, The Clash, Kraftwerk, Black Keys, Jane Weaver, an astonishing interview with Sonny Rollins among many other highlights. Critically, we have a very busy reviews section, which I hope is a strong indicator of the wealth of new music we can expect this coming year. Here, too, are a ton of new releases for your delectation. Some of these – like Sunburned Hand Of The Man, Cory Hanson, Jane Weaver, Chuck Johnson and Julien Baker – you can also read about in our new issue.

Follow me on Twitter @MichaelBonner

1.

SUNBURNED HAND OF THE MAN

“Flex”

(Three Lobed Recordings)

2.

THE ANTLERS

“Solstice”

(Transgressive)

3.

JAMES YORKSTON & THE SECOND HAND ORCHESTRA

“There Is No Upside”

(Domino)

4.

CORY HANSON

“Angeles”

(Drag City)

5.

JULIEN BAKER

“Hardline”

(Matador)

6.

LNZDRF

“Brace Yourself”

(self-released)

7.

JANE WEAVER

“Heartlow”

(Fire)

8.

MENAHAN STREET BAND

Make The Road By Walking

(Daptone)

9.

CHUCK JOHNSON

“Raz-de-Marée”

(VDSQ)

10.

ALTIN GÜN

“Yüce Dağ Başında”

(Glitterbeat Records)

11.

BILL CALLAHAN & BONNIE “PRINCE” BILLY

“Lost Love” [feat. Emmett Kelly]

(Drag City)

12.

MOUSE ON MARS

“Artificial Authentic”

(Thrill Jockey)

13.

HISS GOLDEN MESSENGER

“Sanctuary”

(Merge)

14.

JOHN GRANT

“The Only Baby”

(Bella Union)

15.

CARM

“Song Of Trouble” [feat. Sufjan Stevens]

(37d03d)

16.

BOBBY LEE

“Fire Medicine Man”

(Bandcamp)

Hear Tom Jones’ Radiohead-esque new single, “Talking Reality Television Blues”

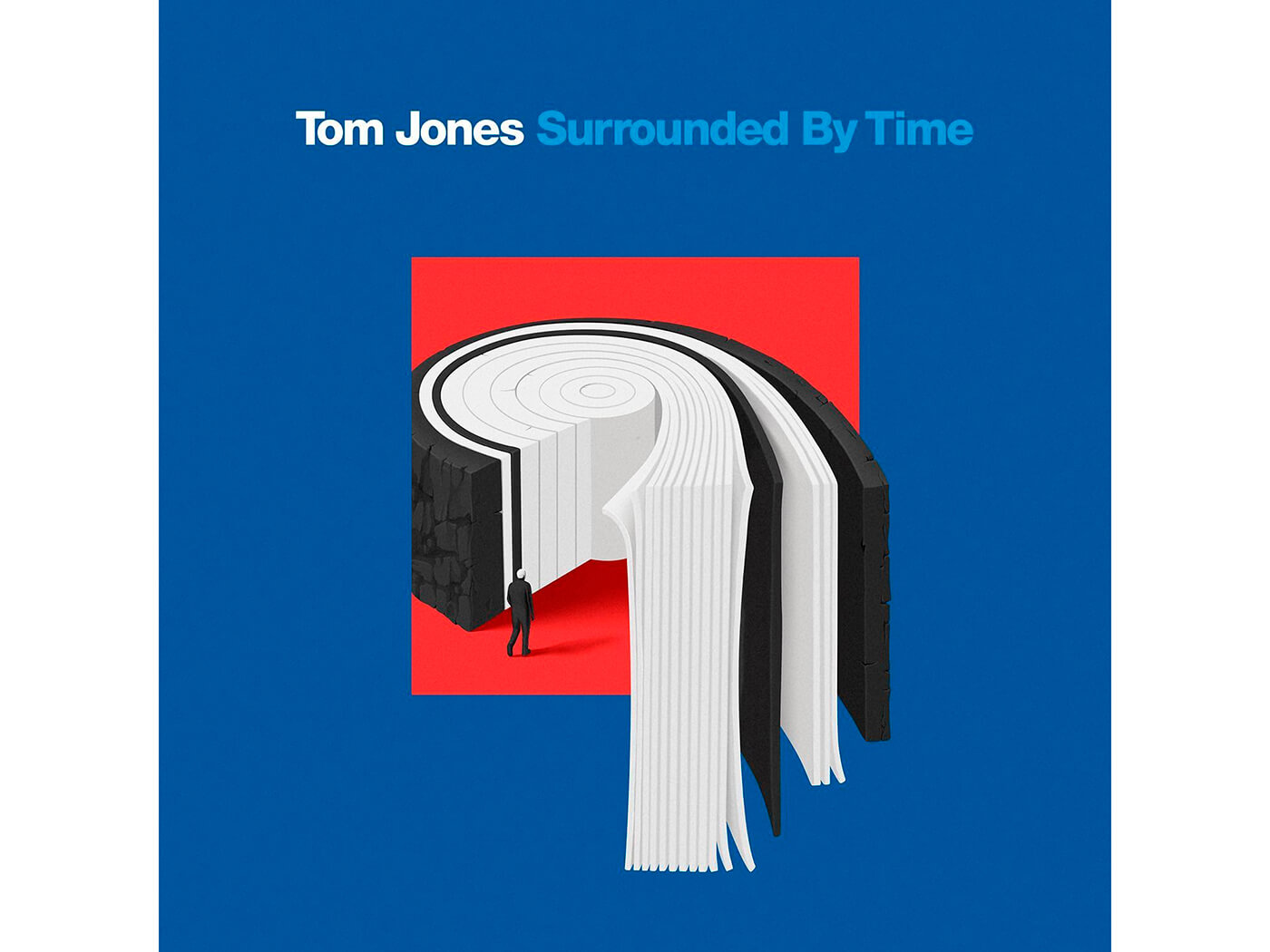

Tom Jones has announced that his new album Surrounded By Time will be released by EMI on April 23.

Produced by Ethan Johns and Mark Woodward, it features cover versions of songs by Bob Dylan, Cat Stevens, Terry Callier, Michael Kiwanuka, Tony Joe White and The Waterboys.

The first single is officially a cover of “Talking Reality Television Blues” by American country-folk singer Todd Snider, although the music bears an uncanny resemblance to Radiohead’s “I Might Be Wrong” (or perhaps Thom Yorke’s “Black Swan”). Either way, it’s a fascinating new direction for the 80-year-old crooner. Listen below:

“I was there when TV started,” says Tom Jones, of the song’s lyrics. “Didn’t know I’d become a part of it – but it could be that its power is to remind us how wonderful, crazy and inventive we are, but also how scary the reality it reflects can be.”

Peruse the full tracklisting for Surrounded By Time below and pre-order here.

Won’t Crumble With You If You Fall (Bernice Johnson Reagon)

The Windmills Of Your Mind (Michel Legrand/Alan & Marilyn Bergman)

Popstar (Cat Stevens/Yusuf Islam)

No Hole In My Head (Malvina Reynolds)

Talking Reality Television Blues (Todd Snider)

I Won’t Lie (Michael Kiwanuka & Paul Butler)

This is the Sea (Michael Scott)

One More Cup Of Coffee (Bob Dylan)

Samson And Delilah (Tom Jones, Ethan Johns, Mark Woodward)

Mother Earth (Tony Joe White)

I’m Growing Old (Bobby Cole)

Lazarus Man (Terry Callier)

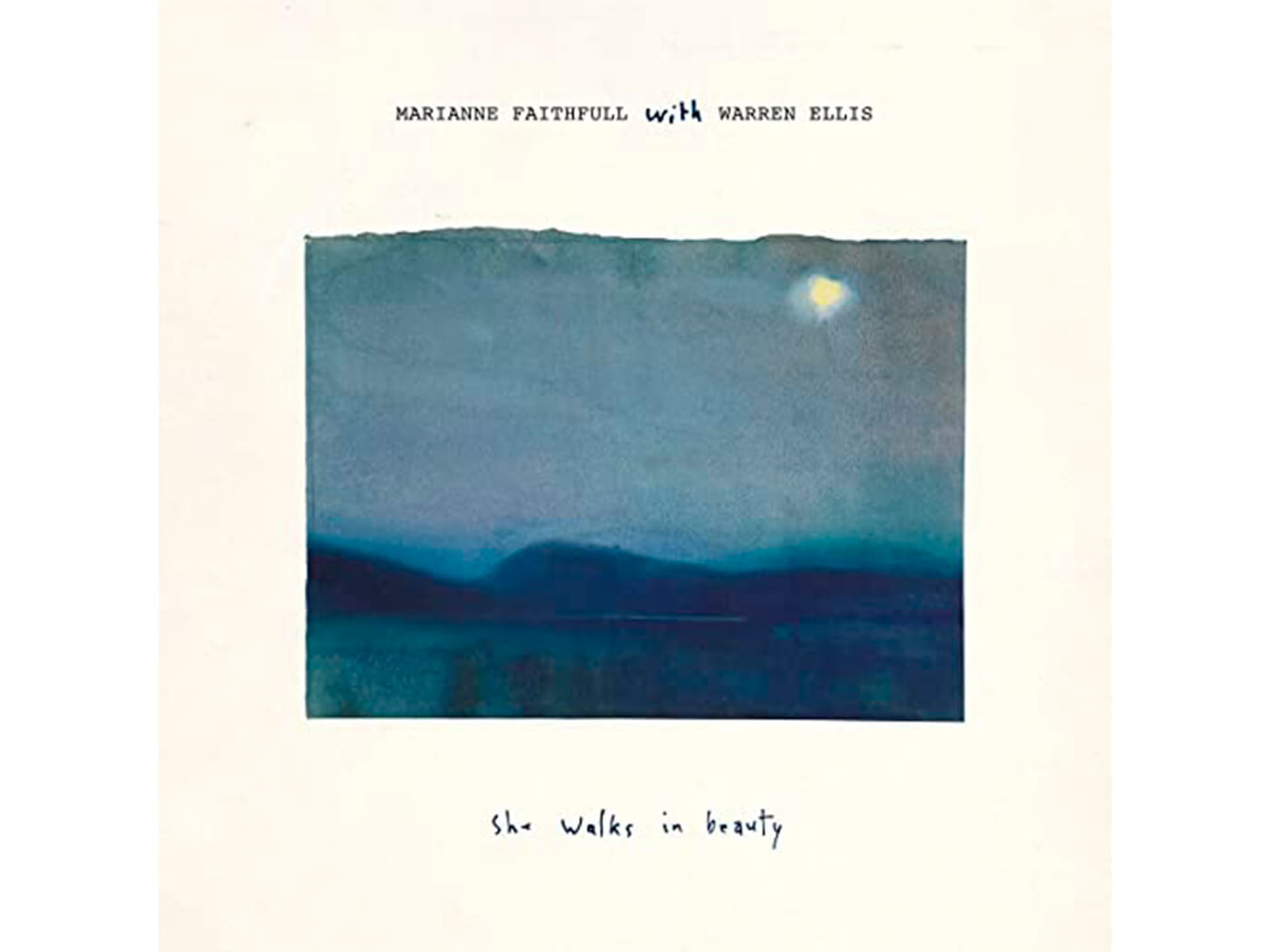

Marianne Faithfull and Warren Ellis confirm release of new album

As previewed in Uncut last month, Marianne Faithfull and Warren Ellis’s collaborative album She Walks In Beauty will be released by BMG on April 30.

Described as a “unique new album of poetry and music”, it also features Nick Cave, Brian Eno and cellist Vincent Ségal.

She Walks In Beauty was recorded just before and during the first Covid-19 lockdown, during which Faithfull herself became infected and almost died of the disease.

“This project has been in my head since I was in my teens, when I was studying English for A-Level and got into the 19th-century English Romantics: Keats, Shelley, Wordsworth and Byron,” Faithfull told Uncut. “I started by recording six or seven of the poems in my flat with [PJ Harvey producer] Head, who mixed them, then we sent them over to Warren. The music he came back with was just brilliant. I’ve never heard anything like it. The first lot of recording was done before Covid. And then post-Covid, I didn’t know if I could even do it any more. It was very sad, because I really wanted to sing the Lord Byron poem ‘So We’ll Go No More A Roving’. But I can’t sing at the moment, because it’s really damaged my lungs. When I had Covid, I was nearly dead. And I’m still recovering. So that poem turned out to be one of the most beautiful, because it’s so vulnerable.

Said Warren Ellis: “Marianne just has one of those voices that’s totally authoritative and full of such colour and such wisdom. It found it very moving and inspiring.”

Pre-order She Walks In Beauty here and see the cover art below.