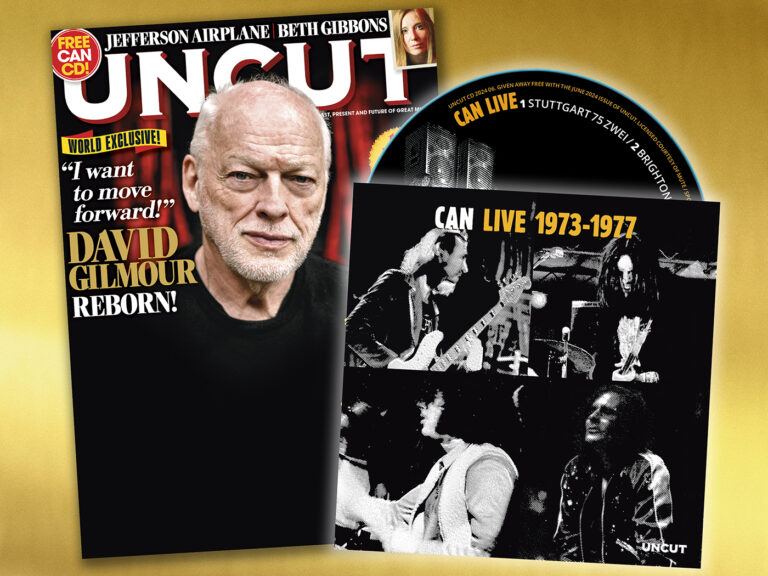

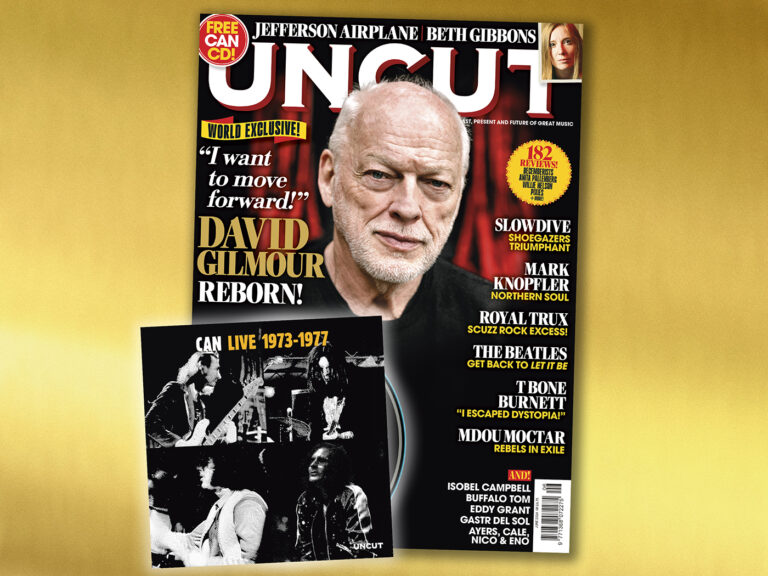

All copies of the June 2024 issue of Uncut come with a free CD – Can Live 1973 - 1977 – that brings together music from Can’s indispensable live series. On these five tracks – don’t feel short-changed: the shortest one is over eight minutes long – you’ll find rock’s most forward-thinking band at their most uninhibited...

All copies of the June 2024 issue of Uncut come with a free CD – Can Live 1973 – 1977 – that brings together music from Can’s indispensable live series. On these five tracks – don’t feel short-changed: the shortest one is over eight minutes long – you’ll find rock’s most forward-thinking band at their most uninhibited…

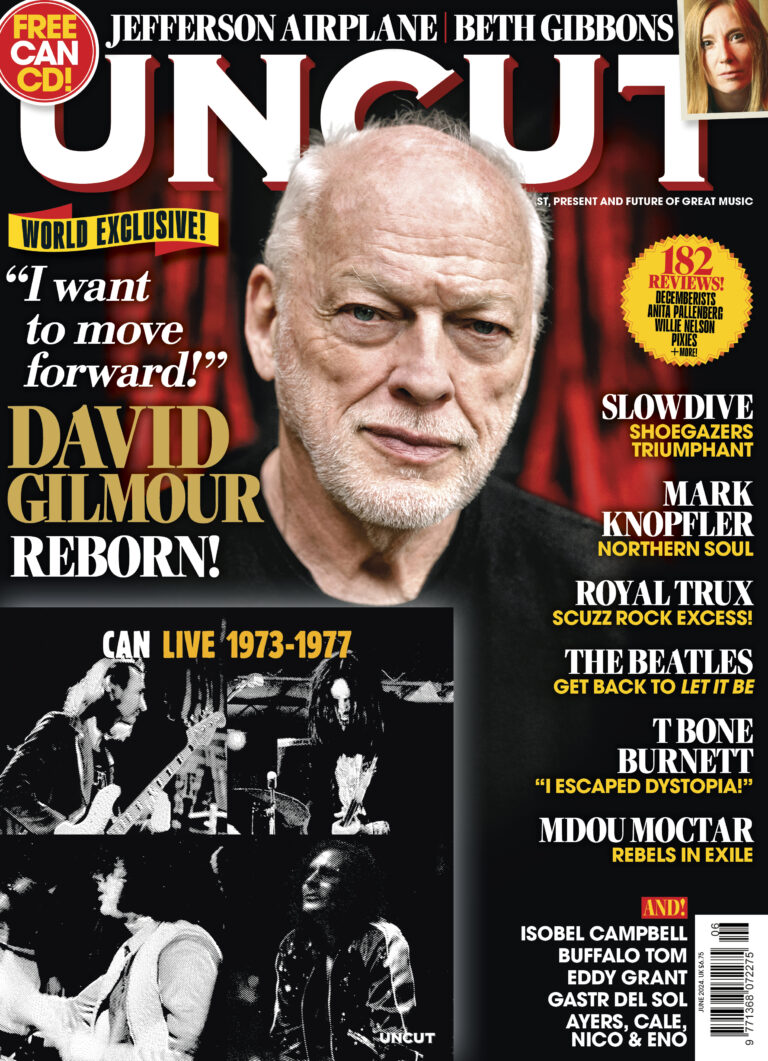

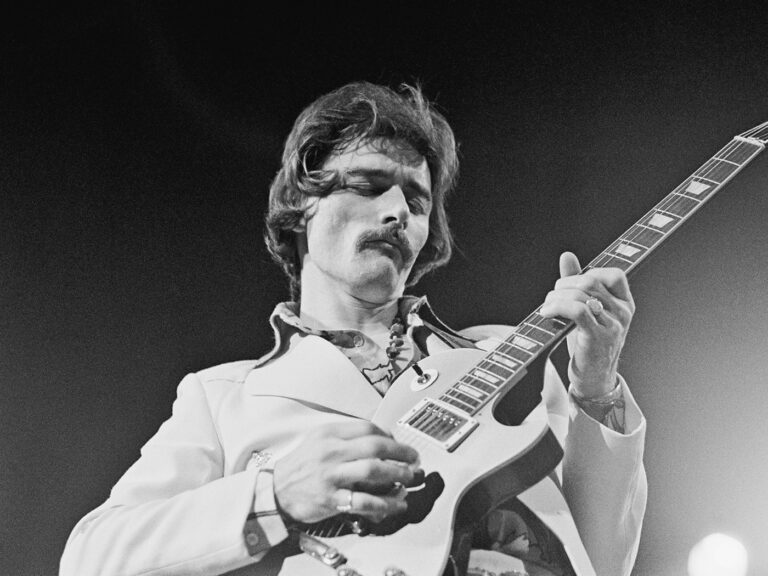

ORDER YOUR COPY OF THE NEW UNCUT, FEATURING AN EXCLUSIVE DAVID GILMOUR INTERVIEW AND A FREE CAN CD!

Technology has brought its fair share of good and bad, but one achievement we can certainly chalk up as a positive is the appearance of Can’s series of live albums. Keyboardist Irmin Schmidt has long been in possession of audience recordings from the ’70s, when the Cologne group were operating at their peak, but the quality was always too poor for commercial release.

“There are now possibilities to improve it in the mastering,” he gleefully told Uncut in 2020. “Documentation of our live appearances is missing from our releases, so I’m quite happy that this gap will be filled.”

Indeed, we’re positively delighted to present to you this incredible sampler of the band’s live series so far. The five epic tracks are drawn from 2021’s Live In Stuttgart 1975 and Live In Brighton 1975, as well as 2022’s Live In Cuxhaven 1976 and this year’s Live In Paris 1973, the first to feature their totemic vocalist Damo Suzuki. The final piece here is a sneak preview of the upcoming release in the series, Live In Aston 1977.

A thrilling 71 minutes of synapse-frazzling head music, Live 1973 – 1977 was compiled in collaboration with Schmidt, now the classic lineup’s only surviving member. Demonstrating his pride in the group’s work – and his, you might say, imperfectionist nature – he had some strict rules: the tracks were to appear in chronological order of release, and no cross-fading or trickery was allowed. We hope you’ll agree that the results, in all their Stockhausen-esque jump-cut glory, are stunning: direct inspiration, illicitly captured on magnetic tape and now brought back to life, its magic intact.

1 Stuttgart 75 Zwei

This 14-minute odyssey shares DNA with Future Days’ “Bel Air”, but keeps mutating into something new. Once Michael Karoli’s guitar takes flight, Jaki Liebezeit doubles the intensity of his attack before Schmidt’s spaceship synths eventually navigate a soft landing.

Irmin Schmidt: “Our live appearances were very different to the records. If there is a similarity to a piece which was on record, it was more a quotation. Even if we did start playing it like on the record, it developed most of the time into something totally different. Sometimes it happened that Holger played ‘Bel Air’ and I played another piece and Jaki drummed something which maybe had a certain similarity to another piece. We used the material but we never really reproduced it.”

2 Brighton 75 Sieben

On which Can take the haunting organ motif from Ege Bamyasi’s “Vitamin C” and use it as the basis for an entirely new piece, resembling the soundtrack to a psychological horror flick with a planet-annihilating climax.

Schmidt: “Live, a guitar riff from one piece could become [the start of] a totally different piece. In this case, I quoted the melody of ‘Vitamin C’. You don’t make it for being kept, it was created in the moment. And don’t ask me what my idea was in that moment, it’s 50 years ago! Every surrounding influenced us: the public, the hall, the atmosphere. When we played in Brighton it was on the pier, and we all agreed the feeling of having water under the floor influenced the music.”

3 Cuxhaven 76 Drei

Evidently invigorated by the sea air of this resort town near Hamburg, Can launch into Soon Over Babaluma’s “Dizzy Dizzy” at breakneck speed. But Karoli soon sets off a series of controlled guitar explosions, as Liebezeit keeps the beat going relentlessly.

Schmidt: “In this moment, it seemed we all agreed, ‘Yeah, let’s play it like that and then see what happens.’ And of course, it developed into something totally different. Even if we improvised onstage, we always went in the same direction in a way that it became a music that was not just bullshit. It was not some kind of jamming and everything falls apart. It was always something which was very connected. It was, in a way, creating forms onstage and really composing, not only deconstructing.”

4 Paris 73 Fünf

For all their improvisatory urges, Can weren’t averse to playing ‘the hit’ if the feeling was right. From the only album of their live series to feature the incantations of Damo Suzuki, this is a rollicking version of “Vitamin C”, which eventually blasts off into other galaxies.

Schmidt: “The whole concept of the live records was that we don’t put single pieces, but to have a whole set of one concert, so you can experience the kind of structure we created over an hour and a half of music. Because we collected these from fans and tapes they recorded illegally, sometimes they end abruptly. It’s not like we ended like this, it’s just the guy got bored having his hand up with a recorder!”

5 Aston 77 Drei

As yet unreleased, the next instalment of Can’s live series – captured in early 1977 at Birmingham’s Aston University – features the band’s reconfigured lineup, with Rosko Gee on bass and Holger Czukay moving to electronics and radio manipulation. The result is a lighter, more agile sound.

Schmidt: “It worked very well, but something in the spirit changed. Holger’s bass playing didn’t have this professional preciseness Rosko had, which of course Jaki liked very much. But Holger’s unusual and sometimes very dramatic way of using the bass had a very special uniqueness. Nevertheless, the next live record we will release is Keele [also from 1977], and that’s great. It shows a totally different feeling between Jaki and the bass, which is also wonderful.”