A rare and remarkable interview with the elusive folk singer

NEIL YOUNG IS ON THE COVER OF THE NEW UNCUT – HAVE A COPY SENT STRAIGHT TO YOUR HOME

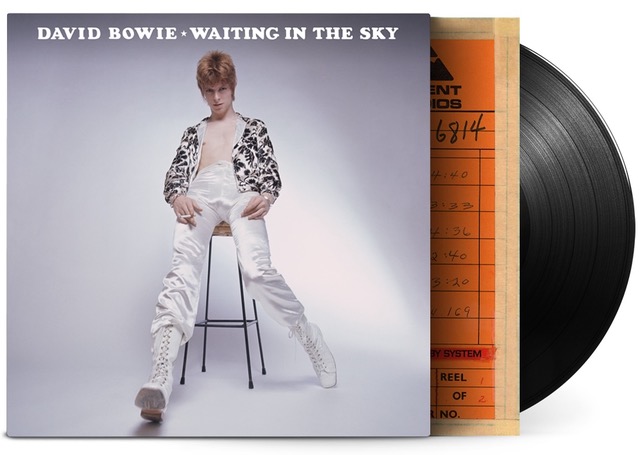

To coincide with the Topic CD given away free with the February 2024 issue of Uncut – which includes an exclusive, previously-unreleased Anne Briggs song – here’s our interview with the elusive folk singer that originally appeared in Uncut’s April 2019 issue; a deluxe edition of Briggs’ self-titled 1971 album will be reissued later this year by Topic

One of the wildest talents of her generation, ANNE BRIGGS retired from music in 1973, leaving only a handful of recordings behind her. Now, in a rare and remarkable interview, this most elusive of folk singers talks frankly with Jim Wirth about her extraordinary life, her brief but indelible career – and why it had to end so soon.

Anne Briggs is reading the labels attached to the trees in Kew Gardens. Slight but steely, she veers off the path at every turn, silently trampling across lawns and occasionally clambering up raised beds. If she could drown out the noise of the aeroplanes coming in to land at Heathrow, she might almost be in her element. The most mythologised singer of the 1960s folk revival has lived in rural Argyll for the past few decades, and her animal instincts have been frazzled by a rare visit to London to attend Topic Records’ 80th-birthday celebrations at Cecil Sharp House. Dressed today in jeans, a red zip-up jumper and hiking shoes, she reluctantly comes out of the greenery and folds herself into a seat in Kew’s café. “I find being in the city totally devastating,” she tells Uncut, hands in constant motion. “Bad. I lose my sense of direction. I get lost. All the time, I get lost.”

Briggs was no less disoriented when she first moved to the capital aged 17, drawn south from nottinghamshire by the prospect of independence more than recognition. An instinctively brilliant interpreter of traditional song, Briggs became a subtle, elliptical writer on a par with her on-off boyfriend Bert Jansch, with a dangerous reputation to match. In a 1971 edition of Sounds, folk critic Jerry Gilbert summed the footloose Briggs up as “a female Kerouac”. However, the 74-year-old is adamant that her rambling role model was never On The Road’s Dean Moriarty, but instead the feral child of Rudyard Kipling’s Jungle Book. “I learned to read when I was about five years old and all I wanted to be was Mowgli,” she says. “Mowgli could do all of the things I wasn’t allowed to do.”

Briggs effectively retired from music in 1973, after deciding that a lone foray into folk rock – released decades later as Sing A Song For You – was not good enough to be released. Pregnant with the second of her two children, she abandoned what was left of her singing career to work in some of Britain’s remotest places with her partner, forester Pat Delap.

“I’ve always been an outside kind of person,” she says, struggling to be heard above the sound of the air conditioning. “I’ve been a professional gardener in one form and another. I’ve spent the past 20 years outdoors; I had a contract with the Forestry Commission and then with the Crown Prosecution Service, helping the guys who are doing community service – keeping their clients occupied.”

In 11 years as a singer, Briggs released an EP and two full-length albums, as well as recording tracks for two Topic Records compilation albums – 1963’s The Iron Muse and 1966’s saucy The Bird In The Bush – and 1963 and 1964’s Edinburgh Folk Festival LPs. Even factoring in Sing A Song For You and “Four Songs” – a more recent EP of pieces scavenged from old radio sessions and a live tape – her entire recorded output amounts to barely three hours of music. However, the extraordinary power of her voice, supernaturally clear and eternally distant, has given Briggs an abiding appeal like few of her contemporaries. “I love the almost dispassionate delivery of Annie, and the starkness,” modern folk polymath Eliza Carthy tells Uncut. “The directness of the delivery and the purity of her voice – it’s like a dagger. It cuts right through you.”

“It’s all there on the albums,” adds Steve Ashley, Briggs’ long-term friend and one-time collaborator. “You can still hear that magic. She was also completely unpredictable.”

On bad nights, Briggs dissolved on stage, forgetting lyrics and abandoning songs as she battled with her profoundly ambivalent attitude to performing. She always sang with her eyes tight shut, making no attempt to reach out to the crowd; her transcendent nights might be the ones when she managed to blank the audience out entirely. “I was always singing to myself,” she says, momentarily cheery. “I hated being in front of an audience. I was nervous. I was just so fucking nervous. I’m so fucking nervous being here with you. I didn’t like being watched. I didn’t like having my photograph taken. Perhaps I felt that I was never empowered to be important.”

Anne Briggs was born in Toton, Nottinghamshire, on September 29, 1944. Now one of Nottingham’s western suburbs, Briggs says it was “a little rural pocket” during her childhood. Her upbringing was no bucolic idyll, though. World War II cost Briggs both her parents; her father – a sapper – contracted tuberculosis while on active duty, and her mother – a nurse – was diagnosed with the same condition at the time that her only daughter was born, dying when Briggs was five.

“She never left hospital,” Briggs says. “I only have one memory of her, which is looking up at this lady who’d been painted. It was a big day for her and the nurses: her daughter’s coming to visit her, and they made her up, bright red. It frightened me. She was like a puppet.”

Briggs’ paternal Aunt Hilda and her husband raised her as their own, but never really explained who the woman in the sanatorium was. “I had no idea at all,” she says, pushing the voice recorder further away. “I think that did influence the way I developed as a human being. I don’t know who I am, I don’t know what I am, but I am.”

If the human world brought fear and confusion, nature was Briggs’ salvation; another uncle, a conservationist, helping to spark her lifelong interest in flora and fauna. However, the would-be Mowgli found manmade forces conspiring against her again once she started to explore on her own.

“I resented hugely, from the age of about 11, the way that girls were treated,” she says. “I wasn’t allowed to wear trousers! I was a real outdoor girl, out in the woods all the time, and if you haven’t got trousers you just end up with scratched legs.”

She questioned the world around her more as she got older, insistently pushing the boundaries. “In the village I came from I was known as ‘the Bohemian’,” she says, rolling her eyes. “I was quite hard work for my uncle and aunt, because we were in this little village community and I wasn’t behaving in the right way. I didn’t see it that way. I just saw there was an inevitability that I had to pursue all possibilities, and I was particularly pissed off with the role in life for working-class girls. So pissed off. It was awful.” She twists her fingers. “That I would be a hairdresser. I was a clever girl! A hairdresser! That was the aspiration: your own little salon.”

Defying those limited expectations, Briggs made it to sixth form, where she studied Art, French and English. Her aunt and uncle felt she might be the first person in her family to make it to university, but the arrival of the Centre 42 festival in Nottingham in the summer of 1962 was to change everyone’s plans.

A trade union-sponsored travelling event aimed at decentralising art from London, it hinged on the discovery of local talent. Having learned folk songs off the radio, and the records of Isla Cameron and Mary O’Hara, the 17-year-old Briggs auditioned to appear, and was invited to sing on stage the following night, a one-off engagement gradually morphing into a longer tour, and then a decision to quit school and run away with the circus.

“My family were so angry with me,” Briggs remembers with a tinge of sadness. “They were prepared to subsidise my way through university. But after a year of doing A-levels, I realised what a drain I was on my substitute parents; I was a terrible drain on a working-class income and would continue to be so, and I thought, ‘I can’t go there; I can’t do this.’”

Briggs moved down to London, initially taking refuge at the Bloomsbury flat owned by Gill Cook – who worked at folk record shop Collet’s, and was the benign house mother to the folk revival’s waifs and strays. The singer’s family tried to get a court injunction to haul her back to Toton, but – since she was only weeks away from her 18th birthday – gave up. All of a sudden, Briggs felt she might have the freedom she wanted.

“I’d always sung, but it had never occurred to me that I could make an income from it,” she explains. “Gill Cook’s flat was next door to Sidney Carter, who wrote ‘Lord Of The Dance’, and I’d occasionally babysit for him and his wife. Centre 42 said they’d give me five quid a week as a go-fer. And I thought, ‘Yes – I’ve got a living.’ I was independent!”

She was also a unique talent; untutored but certain of herself, she bewitched the young vanguard of the folk revival with her natural style of singing traditional songs. Frankie Armstrong – later Briggs’ co-star on The Bird And The Bush – witnessed one of her first London engagements. “This quite small figure just stood up and sang like a bird, with that sense of freedom and purity,” she tells Uncut. “I was just absolutely mind-boggled. In terms of singing the kinds of songs she was singing at the time, I didn’t think there was anyone to match her.”

However, while she bonded with Jansch and the Watersons – all children, as Briggs points out, with family backgrounds as complicated as her own – she never found a comfortable niche in the factional London folk world. Topic doyen AL Lloyd kept her supplied with superb songs (not least “The Recruited Collier”; her version on The Iron Muse remains the definitive one) but she was more comfortable doing ad-hoc spots in north London’s Irish pubs.

“There was a bunch of Irish labourers who’d tell me where they were going to be drinking, and I’d go along,” she says, smiling. “They’d play the fiddle and the flute, and I’d sing unaccompanied – and they’d say, ‘All right, you’re one of us.’ That was so important to me. I had no awareness of the class thing; I just knew we were all at the bottom of it, but the Irish guys just seemed to adopt me and look after me.”

Topic released Briggs’ solo EP “The Hazards Of Love” in 1964, the captivating sleeve shot – taken by Brian Shuel during the recording of The Iron Muse – trapping the camera-shy singer looking like a French Nouvelle Vague heroine, grainy and unknowable. It largely featured pieces Lloyd had picked out for her – not least her rewiring of sea shanty “Lowlands” as a mournful love song. Warwick siren June Tabor, for one, felt it was a magical record, telling Uncut: “It’s completely unselfconscious. It had the decoration of an Irish style of singing, but there was a lot of her and her Midlands self as well. It was a music that gave me memories of things I never could have known.”

However, Briggs’ interests moved beyond unaccompanied folk as the decade wore on. Having worked together with Jansch during their off-days from touring, Briggs began to amass a small kernel of songs of her own, the mournful “The Time Has Come” being recorded somewhat perversely by The Alan Price Set in 1967, long before she committed her own version to tape in the early 1970s. She also began to quietly absent herself from Britain, spending more time in Ireland with Johnny Moynihan, from Dublin imps Sweeney’s Men, the couple busking and adventuring together for several years. Future Wings guitarist Henry McCullough saw them at close quarters and reckoned they were “the first hippies” – in Ireland at least – with Briggs subsidising their lifestyle with occasional trips back across the sea. “I’d come over to England, do a few gigs to get money then leg it back to Ireland and just live,” she says.

Such was her unworldliness that she spent part of the summer of 1967 living alone on a beach in the west of Ireland, an experience she recounted on her stark signature tune “Living By The Water” – key line: “Because I need no company, I make no enemies.”

“I did live on a beach,” she says. “Alone. For several weeks. I was totally happy with that. I didn’t want to be tied down; anybody putting pressure on me, I didn’t want it.”

Freedom had its pitfalls, though, especially for women, as she was reminded once she moved back to England. “I actually got a lift from Fred West,” Briggs says. “He had his daughter Charmaine in the car and his brother as well. I was hitchhiking with my lurcher, Clea. They stopped and picked me up not far out of London, because I was going back to Nottingham to spend time with my family, who had eventually decided that they would speak to me again.” It’s not a story she cares to elaborate on. “let’s not go there.”

Lloyd eventually persuaded Briggs to record a debut LP for Topic in 1970, by which time she and Moynihan were living in a caravan in little Bealings, Suffolk, scuffing by on seasonal work. In a letter to Topic label manager Gerry Sharp, she begs for a £5 advance explaining, slightly over dramatically, “I broke my back strawberry picking last week.”

Released in early 1971, with Briggs and Clea depicted in silhouette on the cover, Anne Briggs opens with her stunning take of “Blackwater Side”, the traditional favourite slowed to crawling pace like some Pre-Raphaelite version of The Velvet Underground’s “Pale Blue Eyes”. More revelations follow, unaccompanied performances interleaved with a couple of Briggs’ songs and a spellbinding “Willie o’Winsbury”, with Moynihan on bouzouki. The Scottish ballad catches the king preparing to have hanged the man who had made his daughter Janet pregnant, only to be bewitched by his beauty: “If I was a woman as I am a man,” sings Briggs. “My bedfellow you would be.”

Briggs’ rapturous rendition acknowledges its power for a more sexually liberated age. “It was phenomenal and I knew it,” she says. “The whole thing of ‘Willie o’Winsbury’ is that it’s potentially homosexual, and I thought that was absolutely perfect and right.”

That Anne Briggs contained self-penned songs was something of a departure from Topic’s staunchly traditional MO. Briggs herself had doubts that self-expression fitted the Topic brand.

“I’ve never told anybody this, but I felt guilty for having written things,” she says, nudging the voice recorder a little further toward the edge of the table. “like, am I betraying something? I really felt I was sort of impure.”

Anne Briggs is a beautiful record, but – as with her entire output – not a piece that inspires fond memories. “I had a bad cold at the time,” she says. “I really found it difficult to sing at all.”

Singing, though, remained a less back-breaking way of making a living than fruit picking, and it was perhaps in the hope of a less hand-to-mouth existence that Briggs signed up with manager Jo Lustig, the New Yorker hustler who made mainstream acts of Pentangle and Steeleye Span. Her legend enhanced after Sandy Denny included her tribute to Briggs, “The Pond And The Stream”, on 1970’s Fotheringay LP, Briggs had a second album in the racks by the end of 1971, Lustig having persuaded CBS to chance their arm on the beeswing-fragile The Time Has Come. A collection that draws together more of Briggs’ songs and works by her peers – Steve Ashley’s “Fire And Wine”, Lal Waterson’s “Fine Horseman” and “Step Right Up” by Henry McCullough – the badly out-of focus sleeve reflects the hazy music within, Briggs demonstrating her inimitable ability to sing a song like she’s not in the room on “Ride, Ride” and the Nick Drake-y “Tangled Man”. However, if it’s deceptively strong, Briggs feels her intentions in recording it were not entirely honourable. “I got pregnant and I had no idea of how I was going to survive, how I was going to provide for my child,” she says. “And CBS offered me 500 quid to produce an lP a year for five years.” She smiles ruefully. “And I fucking blew it.” Her aversion to paying her musical dues was underlined when Lustig booked her to support Jansch at the Royal Festival Hall on June 30, 1971. Wearing a borrowed pink maternity outfit, Briggs felt utterly out of place, and was further unnerved when her manager had a bunch of flowers delivered to her on stage. “Jo Lustig was trying to make me into something I didn’t want to be,” Briggs says, extending her arms out wide. “He wanted me to be an arm-flinger.”

Like the Shirley Bassey of folk?

“Yeah.” She pauses. “No way.”

Briggs was weary of the fight long before her final musical act, when she invited Ashley’s newformed folk-rock ensemble Ragged Robin to back her on a putative second CBS record. The group were given barely a day to rehearse with Briggs – who had never performed with a backing band – before being whisked off to the studio.

“Anne hadn’t heard the band and I also knew she disliked recording,” Ashley tells Uncut.

“However, when she arrived and met everyone she was in good form and the rehearsals went well. Unfortunately, the wild spirit of the rehearsal became more subdued in the studio. But still, with so little time available to us – we only had a couple of days – I think it turned out pretty well.”

The traditional “Hills of Greenmore” and Briggs’ own “Summer’s In” and “Travelling’s Easy” are wistful and luminous, while there is a little more Liege & Lief thunder in “Sing A Song For You” and “Sullivan’s John”, but Briggs remains profoundly ambivalent about the recordings: “I was pregnant again. I did it purely for money. I thought: ‘I’ve got to provide for the babies.’ I’d got two of them, one in there,” she says pointing at her waist “and one being carted around.” Briggs disliked her singing on the record so much that she forewent the £500 to block its release, and abandoned any plans to sing again.

“I had no options,” she says, hackles rising as she bats away questions about why she stopped. “I had no options.”

Because of money? Because of the responsibility of having children?

“Don’t push it. No. I was saying to you: I had no options.” And that’s all she is prepared to say.

The light is fading at Kew Gardens; in a few minutes the staff will be ushering us out. Briggs needs a rest. “I find talking for any length of time really difficult,” she explains. She has managed to cut her tongue while lighting a cigarette; the filter is stained with blood as she tells Uncut about her children’s taste for endurance sport. For her part, Briggs reckons that she could still comfortably survive a night or two in the wilderness. “I’ve had a hard life,” she says, seeking no sympathy. “I’ve had a really hard life.”

A return to performing may be more than she can handle, though. She has been lured back on stage a handful of times in the past 46 years, but hideous stage fright ruined every performance. She has never stopped writing and still owns her bouzouki, but any talk of more music is off the table as she packs up her grey rucksack. “That’s not a good place to go,” says Mowgli, slinging her bag over her shoulder. If the manner of her departure from music was not of her choosing, she is taking a dark satisfaction in controlling the narrative now. “We’ve had a good chat,” she says with an air of finality as she heads for the exit. She is leaving on her own terms; going her own way.