It’s recently been announced that a rare live recording of Syd Barrett guesting on guitar with The Last Minute Put Together Boogie Band in Cambridge in July 1972 is to be released – so now seems like a perfect time to revisit the extensive tribute we published in Uncut just after Barrett’s death in July 2006 (Take 112, September 2006). As well as a fantastic piece written by David Cavanagh, we hear from Syd’s friends, collaborators and admirers, including David Bowie, David Gilmour, Mick Rock, Peter Jenner, Damon Albarn, Julian Cope and Kevin Ayers. Shine on…

___________________

In the end, after 35 years of declining to countenance the far-reaching impact of his talent on the history of rock’n’roll, Syd Barrett departed his dark globe peacefully, aged 60, in Cambridge on July 7. Early reports indicated that his death was due to complications arising from diabetes/cancer. He left the world as he had lived in it for the past 25 years (and for the first 15): not as the tousle-haired poet/star ‘Syd’, but as Roger Barrett, a lover of painting, a private citizen, a non-musician. He had lived alone in suburban Cambridge since his mother’s death in 1991, and had been diagnosed as a diabetic – following more than three decades of mental illness – in 1998.

What has been lost to us? Barrett, in a former existence, was spectacularly gifted, one of the most original songwriters and true visionaries that England has ever produced. Arguably the key musical personality of 1967 on either side of the Atlantic, he was on a par with The Beatles for most of that year, and might conceivably have outstripped them if his terrible LSD-related problems hadn’t stopped him in his tracks. Which they did straight afterwards.

What has been lost to us? Barrett, singing from a lonely place an awfully long time ago, gave posterity two scruffy, endearing, fragmentary solo albums to remember him by when he took his absence. Which he did straight afterwards.

What has been lost to us? Nothing in real terms, you could unsentimentally argue. There was never any serious question of a comeback after all these years; and by all accounts Syd Barrett ceased to exist as a person a long time ago anyway. What has been lost to us? Only the ridiculous hope that an impossible miracle could have happened. And now there’s only the desperate sadness that poor Syd Barrett is dead.

Barrett – although it’s always been debatable whether he knew it – was a famous man in Britain long after his premature retirement in the early ’70s. Perhaps he did know it, but needed to disbelieve it for the sake of privacy and peace of mind. He did not solicit the public’s respect during the next 30 years; but they gave it to him, unsolicited, all the same. In absentia – and there has never been an absentia quite like Barrett’s – he joined the ranks of the most revered figures that rock has ever known, without apparently hearing one single note of music played by any of the artists he influenced. Was he aware of Julian Cope? Did he check out the Britpop boys? Had he heard the Mary Chain’s version of “Vegetable Man”? You have to say it’s unlikely. The last time Barrett released a record, Ted Heath was prime minister and Britain had not yet gone decimal.

“The past is not something Rog ever discusses,” Ian Barrett, his level-headed-sounding nephew, wrote in a mid-’90s email correspondence with a Pink Floyd fansite. “[He] is so removed now from the glamour and excitement of the showbiz world… I’m sure it confuses him that anyone else would care so much that he sang a few songs and played a bit of guitar in the ’60s.”

By the time his nephew’s words were written, Barrett’s life – and his indefinite absence – had already inspired several books and a plethora of ‘anniversary’ retrospectives in magazines. It was 20 years since he had vanished. It was 25. Bloody hell, it was 30.

In 2001, Barrett was the subject of an Omnibus documentary on the BBC, in which David Gilmour and Roger Waters from his Pink Floyd otherlife spoke warmly of him. Barrett himself didn’t appear: this was not a surprise as the Floyd hadn’t seen him since 1975 (and they hadn’t even recognised him then). It is said that Barrett watched the programme at his sister’s house when it went out, and showed some pleasure at the old footage of “See Emily Play”. But he deemed the proceedings as a whole to be “a bit noisy”. Perhaps it’s a good job he never heard the Mary Chain.

For the most part, according to his nephew, Ian, the memories of his pop star heyday were so painful that Barrett couldn’t bear to think of them. He was “simply [not] interested in going back over a time in his life that precipitated his breakdown and retreat from society.” So we’ll probably never know whether the reclusive Barrett was having an evening with the TV switched on or off, when the following words were broadcast to the world. “Anyway, we’re doing this for everyone who’s not here,” said Waters at Pink Floyd’s Live8 reunion last summer, “particularly, of course, for Syd.”

Roger Keith Barrett was born in Cambridge on January 6, 1946. The youngest of five children, he grew up in comfortable middle-class surroundings, receiving encouragement from his parents in both music and art. After attending school in Cambridge, where he met the future Pink Floyd musicians David Gilmour and Roger Waters, Barrett won a scholarship to Camberwell Art School in London. By his mid-teens he’d acquired the nickname, Syd, a misspelt reference to a Cambridge drummer, Sid Barrett.

In London, Syd was invited by Waters to join a collection of musicians who had variously been calling themselves Sigma 6, The Tea Set and The Abdabs. Barrett climbed aboard one of the final incarnations – which tellingly included Waters (bass), Rick Wright (keyboards) and Nick Mason (drums) – but renamed them The Pink Floyd Sound, juxtaposing the first names of two bluesmen, Pink Anderson and Floyd Council, whom he’d recently read about on a record sleeve. By 1966, the band had shortened their name to Pink Floyd and were playing around London, where they were soon swapping their repertoire of American R&B covers for newly written, and highly experimental, Barrett material.

Signed to EMI in early 1967 as the leading lights of London’s new psychedelic underground, Pink Floyd released their debut single, “Arnold Layne”, in March. Stunningly original (and much different to the open-ended improvisations of their live show), the Barrett-composed song invited the listener’s compassion for a transvestite who is arrested for stealing women’s clothes from washing lines. When Arnold is imprisoned at the end of the song, the sense of injustice in Barrett’s voice is palpable (“he hates it!”).

The song was brilliant. Barrett, indeed, was now in an exceptionally creative period that would last throughout 1967. As a wordsmith, he was able to map out a long-term blueprint for British psychedelia that took elements from sci-fi and children’s stories to create an utterly rapt lysergic atmosphere of syllables and textures – of futures and histories – of adventures and escapades – alternately taking place in exquisite leafy gardens, in outer space and in a fantasy nursery where the only interruptions come from that great psychedelic Barrett standby: the soothing maternal presence. Aaaah, Mother.

It had been noted by friends that Barrett was taking a lot of acid in the early months of 1967. On stage he’d been exploring the outer limits of the rock avant-garde with Pink Floyd at their increasingly popular acid-soaked rave-ups in the capital. In the studio, meanwhile, Barrett had revealed an unexpected flair for writing thrillingly kaleidoscopic, yet perfectly concise singles – the Top 20 hit, “Arnold Layne”, was followed by “See Emily Play” (which reached No 6) and the breathtaking “Apples And Oranges” (an unaccountable commercial failure).

It’s in the former that we hear Barrett’s middle-class vowels at their most seductively enunciated (dig that crazy meticulous BBC English!), but it’s in the seldom-heard latter that we really appreciate how close Syd Barrett came to being a genius. “Got a flip-top pack of cigarettes in her pocket/Feeling good at the top, shopping in sharp shoes…” The outrageous tongue-tapping syncopation of his opening couplet is matched by his innovative use of guitar, not least his superbly controlled feedback and wah-wah. But outside his music, control was now slipping away disastrously from Barrett. He had lost the attention of the public, and his friends feared he was losing his mind to acid.

Floyd’s co-manager Peter Jenner told Uncut in 2001: “During that summer [’67], Syd was becoming increasingly difficult. At some of the UFO gigs, he’d play one note all night. Even though he was tripping on acid, I thought that was odd behaviour…”

The pressures on Barrett had become considerable, especially if one bears in mind that he may have been required by 1967’s unstoppable chain of events to be simultaneously Pink Floyd’s breadwinner, their de facto pop idol, their creative lynchpin and their most extravagant LSD-taker. Barrett had peaked musically in the summer of ’67 with the release of the Floyd’s debut, The Piper At The Gates Of Dawn, a masterpiece that he’d written almost entirely on his own. It was to be the only album he ever completed with Pink Floyd.

Barrett behaved unpredictably from the autumn into the winter. In Santa Monica on the US tour, he squeezed a tube of Brylcreem (which he then mixed with crushed Mandrax) on to his head prior to a gig, so that his face appeared to be melting horrifically under the lights.

In early 1968, his old Cambridge friend, Dave Gilmour, was asked to join Pink Floyd as a second guitarist – but really as emergency cover for Barrett if the latter’s deterioration continued. It did. After only a handful of shows as a quintet, during which Barrett’s antics infuriated his colleagues once too often, the unstable frontman was asked to leave the Floyd in April 1968. Two months later, “Jugband Blues”, a song he’d recorded before his departure, emerged as a poignant and deeply quizzical valedictory statement on the new Floyd album, A Saucerful Of Secrets. Barrett sounded for all the world as if he knew there was no way back.

As Pink Floyd and Syd Barrett took their respective forks in the road that spring, it was supposed to open up bright new possibilities for Barrett as a solo artist. Free of the pressures of commercial expectation, there was hope that he might flourish – or at least start to recover. At first, though, he seemed incapable of comprehending that he was no longer a member of Pink Floyd. He would turn up to their gigs with his guitar, and have to be told in no uncertain terms that he wasn’t going to be permitted to play. Nor did Barrett’s solo career begin too auspiciously. Peter Jenner organised a series of recording sessions at Abbey Road, but only a smattering of viable material resulted. Syd’s biographer, Tim Willis, later wrote: “Barrett was all over the place – forgetting to bring his guitar to sessions… sometimes, he couldn’t even hold his plectrum. He was in a state.”

But it must be stressed here that Barrett’s uncanny gifts as a songwriter had not deserted him. There are perfectly sentient people in this world who regard the music Barrett released in 1970 as the best stuff he ever did. Syd’s solo debut album The Madcap Laughs and its follow-up, Barrett, released at either end of the year, were, it’s true, somewhat reduced in musical circumstances if one compares them to the hi-tech Abbey Road studio finesse that producer Norman Smith had applied to The Piper At The Gates Of Dawn. Whereas Floyd’s debut had been, in places, an electronic tour de force to rival Sgt Pepper – all systems blazing, all weapons on ‘stun’ – The Madcap Laughs, by contrast, got underway with the most lethargic strumming of an acoustic guitar ever committed to tape – and a voice with sleep in its eyes singing: “I really love you… and I mean you.”

Barrett upped the psychological ante on a song called “Dark Globe” by hitting a gigantic non-chord to drive home the panic and loss in his words. “Won’t you miss me? [claaaang]… Wouldn’t you miss me at all?? [claaaang, claaaang, claaaang].” The psychedelic voyage – at least in musical terms – had crash-landed with no survivors. On side two , you could almost hear his psyche falling to bits.

But here is the proof of the pudding. Even when there was no news on the Barrett horizon for 20 years, neither LP was allowed to go out of print. Now, both command levels of respect and love that are far removed from the shambolic way in which they were created. Partly, this is because the songs are so fragile (whether charmingly or frighteningly so). Each song sounds so hugely important to Barrett; the anxiety is there in his voice. Touched by his dedication and amused by his wonky humour, but at the same time concerned for his welfare, we are drawn back to these intimate performances again and again. When he died, it was probably to our copies of The Madcap Laughs that most of us instinctively raced.

And then there was silence. And as we now know, it was pretty much unbroken. There was an abortive attempt in ’74 to record him again. The following year, he turned up uninvited and shaven-headed at Pink Floyd’s sessions for Wish You Were Here. The band were distressed by his appearance, and mortified when he tried to clean his teeth by holding his toothbrush steady and jumping up and down on the spot. By the early ’80s, it was generally accepted that there would be no further communications of a musical nature from the former Syd Barrett. He’d moved from London to his mother’s house in Cambridge in ’81, re-adopting his Christian name of Roger. After a brief return to London in ’82, he made the same journey back home to his mother in Cambridge – only this time, he walked. We’re fortunate that we have no idea what that walk must have been like.

From what is known of the last 25-30 years of Barrett’s life, he never married or had children. He never had a job that lasted very long. He liked to paint but had a tendency to destroy paintings he didn’t think were perfect. He ballooned in weight, then suffered an ulcer that made him lose it. He spent time in psychiatric hospitals – but was never sectioned. He was not prescribed drugs for his mental health. He seems never to have had any more direct contact with the band who wrote “Shine On You Crazy Diamond” in his honour. The band that he had co-founded, led and named.

Now and again, incongruously, Barrett’s bald pate and middle-aged paunch would appear in a tabloid, photographed by a paparazzo as he trudged to the shops. For an individual so beautiful in his youth, his appearance now took some getting used to. But because so few photos of latter-day Barrett did the rounds – and because the images of him from 1967-’70 were still so potent – it’s no wonder that his fans preferred to think of him prowling around his London apartment with its black and orange floorboards, or looking lugubrious next to his Mini, or obtaining some astounding futuristic noise from a silver guitar with mirrors on it.

In that context, it seems almost irrelevant to point out that Syd never went out of fashion. He survived punk, disco, house and the late-’80s goth threat. He survived every trend in exactly the same way: by not being there. He literally went away and never came back.

Or did he? We could always hypothesise: there’s nothing to stop us. We could suppose that the indefinite absence did not last, in fact, for all time. Perennial interrogation marks hang over his life even in death, encouraging us to pose the rhetorical question. Did Barrett’s mind allow him a flicker of reminiscence at the end? Did he flash back – did he return just once – to ’67? Did he behold his fabulous 21-year-old self at the helm of Pink Floyd? Did a stoned apparition come to him through the fog and the lights, calling itself ‘Syd’ – were the two lives of Roger Keith Barrett finally reconciled?

But it’s probably too inappropriate a conceit, isn’t it, for us to go there. So may he simply rest in peace…whoever he was.

David Cavanagh

___________________

Farewell, crazy diamond… Tributes from Syd’s friends, collaborators and admirers

David Bowie: “I can’t tell you how sad I feel. Syd was a major inspiration for me. The few times I saw him perform in London at UFO and the Marquee clubs during the ’60s will forever be etched in my mind. He was so charismatic and such a startlingly original songwriter. Also, along with Anthony Newley, he was the first guy I’d heard to sing pop or rock with a British accent. His impact on my thinking was enormous. A major regret is that I never got to know him. A diamond indeed.”

Joe Boyd: “The first time I saw Syd was when Pink Floyd played the All Saints Hall, Notting Hill in 1966. I was blown away. They were a great band, and the slide-show was something one had never seen before. They were the soundtrack to the underground, emblematic of its spirit and mood. And by May ’67, they’d put the underground onto their shoulders, and taken it into the mainstream. Syd’s contribution to that was that he wrote the songs, he sang lead, he played lead guitar. In any other band, he would have been the absolute focus. But because the Floyd’s style of presentation was so anonymous, with everybody merging into this red and pink flashing light, he never really took the role of leader.

“His songwriting was very English. It’s ironic that the Floyd was named after two blues singers, as they set out to be a blues band. But because of Syd, their music is almost devoid of blues. His singing style is completely English, and the songs are of the jaunty, witty music hall type. He’s a classic songwriter in the tradition of Ray Davies, Lennon and McCartney, at that crossroads of music hall and pop.

“He shaped the Floyd’s sound, by his songs and playing and the way he sang. But when I went into the studio with them to produce “Arnold Layne”, Syd was diffident. He’d wander off, go outside and disappear. My memory of the control room was of Roger and, to a lesser extent, Rick and Nick, being present and having a lot to say.

“Syd seemed happy-go-lucky. He had impish girl-magnet looks, and was happy to play on it. He had a very attractive, sexy girlfriend, and she wasn’t the only one he was seeing. Then a couple of months went by, when people talked about Syd taking an awful lot of acid. I saw him at the end of that period, sitting in a London street, and he’d lost all that spark. He became vacant-eyed, even when he was with you. I saw him like that when they played The Roundhouse, later in that summer of ’67… the last time I saw him.

“I thought his solo work was a bit sad. It’s partly because I have very painful memories of this tape he gave me in that winter of ’66, of him playing guitar and singing five beautiful songs he’d written that weren’t really right for the Floyd. And that tape went missing a long time ago. Some of it appeared in slightly wackier form on his later records. But I have this memory of it, as a sort of idealised version of Syd. And when I heard The Madcap Laughs and Barrett, it sounded like a man who I’d known in better circumstances.

“The Syd that I knew vanished from this earth that spring of ’67. I never really knew the other Syd. I had a lot of sadness about Syd in 1967. He was a great and very, very talented guy. And that guy went away. A long time ago.”

Peter Jenner: “As time’s gone on and I’ve worked with other musicians, I’ve realised more and more what a genius Syd was. That’s not just some rosy glow for the obituaries. It’s a reflection of how much influence he had and how Pink Floyd remained his band throughout, even after he’d gone and they were doing their own thing. The band revolved around him and his spirit remained central, even after he went.

“The late ’60s were a key time in terms of profound changes in post-war society and opening new doors and breaking down the old order – and Syd was a vital part of that. He was one of the great songwriters of the 20th century, up there with Lennon & McCartney and Nick Drake.

“Some of his best work was in those last songs he wrote for the Floyd, like ‘Jugband Blues’. They were blinding songs, painful and true, like a Van Gogh painting. When the split came there was never any question in my mind that I wouldn’t go with Syd. I wasn’t a very good businessman and that decision tells you a lot about me. But Syd was the genius in the band in terms of the music and I was going to stick with him.

“The last time I saw him was in around 1980. He came into the office to get some piece of paper signed – a passport application or some such. I didn’t even recognise him at first and then the whisper went around that it was Syd. You wanted to help him. But you really couldn’t.”

Andrew King: “It all went off the rails in the autumn ’67 on their first US tour. I flew out ahead of the band and went to see our agent in New York, a guy called Gimpy. He gave me all the contacts for the shows – two in San Francisco with Bill Graham, one at the Cheetah Club in Santa Monica, one more somewhere and TV slots on the Perry Como and Pat Boone shows and on American Bandstand. Then he opened a drawer and offered me a gun, which he said I’d need on tour. I politely declined and flew to ’Frisco unarmed to meet Bill Graham. We missed the first Fillmore West gig, as they had no visas. Bill rang the US ambassador in London at about 4am, got him out of bed and screamed at him to get the visas sorted.

“They came through and the band arrived. But they were totally dysfunctional from the start. Basically, Syd wasn’t playing anything. He had a whistle, which he’d blow from time to time. The tour should have been fantastic. There I was sharing a bottle of Southern Comfort with Janis Joplin. But it was miserable. Nobody was talking to Syd. I had to chaperone him everywhere to prevent anything too dreadful happening to him.

“The split with the Floyd was very complicated, scary and traumatic. I didn’t think that the future lay with Syd rather than the band, partly because I never made the mistake of underestimating Roger Waters and partly because I’d seen Syd’s problems unravel on the US tour. But I did what I did and we went with Syd.

“I went on seeing him for a while after that. My wife, Wendy, had been at art college with him in Cambridge, so he felt safer with her than most people, because he associated her with his youth before it all went wrong.”

David Gilmour: “We are very sad to say that Roger Keith Barrett – Syd – has passed away. Do find time to play some of Syd’s songs and to remember him as the madcap genius who made us all smile with his wonderfully eccentric songs about bikes, gnomes and scarecrows. His career was painfully short, yet he touched more people than he could ever know.”

Damon Albarn: “I’m no acid basket case, but of course I love Syd Barrett’s songs, especially the ones that sound unfinished. He wrote about his own reality in a way that very few people can. A couple of years ago I made a record called Demo Crazy. Not many people got to hear it, because it was just unfinished scraps of would-be songs I’d recorded in hotel rooms. But it was made totally under the influence of Syd Barrett. It simply couldn’t have existed without him.”

Jim Reid: “I never went along with the idea that Syd Barrett was insane. I dare say he did get frazzled with drugs, but I think there was more to it than that. He was too fragile to be a frontman in a rock band, and that comes across in a song like ‘Jug Band Blues’. He seems to be a guy who has completely lost his identity, and it seems like a desperate cry for help.”

Serge Pizzorno: “I imagine he’s more at peace now, and I hope he is. It was a real tragedy because as a songwriter he absolutely fucking blew my mind. Nobody ever got anywhere near that first Pink Floyd album in terms of psychedelia. The great thing about him was there was always a tune. I loved that. He would go off for 25 minutes, but then he’d bring it back to some sort of melody or riff that’d make you go, ‘Fuck me, that’s GENIUS!’ And he got away with singing about fucking bikes! He was a one-off.”

Julian Cope: “It is with great distress and sadness that I learned of Syd’s death. Although only 60, to put an age on someone as timeless and mythical as Syd is like dating the Pyramids or Stonehenge. When I was given my first Barrett album in 1973, Syd was already lamented as a probable casualty of the ’60s. At that point, 36 months since his last release, we’d all hoped for some sort of artistic rebirth. It’s difficult now to explain just how divided were the opposing pro-Barrett and pro-Pink Floyd camps. Syd has quit this planet far too young.”

Kevin Ayers: “I wrote a tribute song for Syd Barrett some 30 years ago called ‘O Wot A Dream’, which says more about my feelings towards him than any eulogy that I might write today. Syd was lost to us a long time ago, but he has left a legacy of haunted and poetic songs which have the urgency and pathos of someone trying to get somewhere but never arriving, because he didn’t know where it was.”

Ray Davies: “‘See Emily Play’ was on the radio the day before I heard that he had died. It made me laugh, but also made me realise the innocence of the time it was made. It was the silliest and most beautiful example of its time. If only he’d put the drug stuff back until he’d made a few more albums.”

___________________

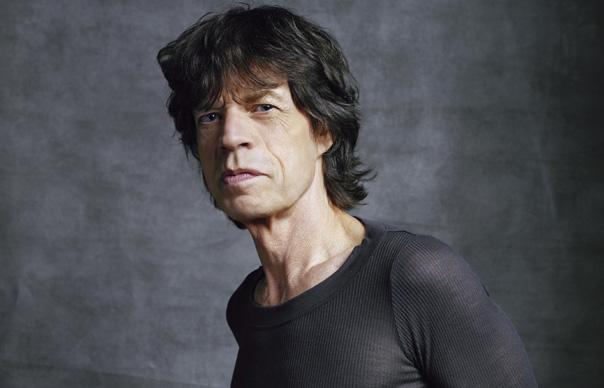

Mick Rock on Syd – the legendary lensman, who took The Madcap Laughs cover shot, looks back at his friendship with “a bizarre and beautiful man”

“I first met Syd back in 1966, when I was studying Modern Languages at King’s College, Cambridge. I knew a few ‘heads’ in the town – a little grouping of guys with names like ‘Fizz’ and ‘Emo’ – those were the sort of names we used to psychedelicise ourselves. We lived in a very narrow world, outside of which we had very little experience, yet our little grouping all had this feeling that we were on the threshold of a new frontier. I certainly felt that when these guys introduced me to Syd and Pink Floyd. It’s hard to convey just what a strange name ‘Pink Floyd’ was in 1966. Every group name was preceded by “The” back then, The Beatles, The Who, The Kinks. What the hell was ‘Pink Floyd’? It turned out Syd had named them after his two cats, who in turn were named after a couple of blues singers.

“I went along to my first Floyd concert in December 1966, just after the end of term. Before I met Syd, I met this very attractive girl, Lindsey, who turned out to be his girlfriend. Right away, I was impressed that he could have a girlfriend like her. As for the gig, ‘unprecedented’ is the only word I can use to describe it. There had not been a sound like this before. And it was definitely the Syd Barrett band. The rest of the band have always been very gracious about acknowledging that. There he was, bobbing up and down amid this bank of flashing lights.

“Anyway, we all went back to Syd’s mother’s house and smoked spliffs. We discussed the Arthur C Clarke science fiction book Childhood’s End, which was quite a cult book among acid heads, especially the bit where the children dance themselves into a state of oblivion. We felt, right then, that we were the children of the future, and Syd was certainly at the tipping end of that. He was bright, beautiful, a visionary… and very friendly. I took a great many moody pictures of him, but really, my abiding memory of Syd is that he laughed a lot. I was still at college when Syd moved to London – but I used to go visit him down there. I’d see him at places like the old UFO Club in Tottenham Court Road – Pink Floyd playing alongside Soft Machine and The Crazy World Of Arthur Brown. I’d sleep over at his various flats, including the one in Richmond Hill. There was a lot of crashing went on back then, amid our small circle of chemical dependents!

“Eventually, after he left the Floyd, Syd moved to a three-room apartment in Earls Court, and that’s where I took the photograph of him which eventually ended up on the cover of The Madcap Laughs, his first solo album. Syd had painted the bare floor of his room in orange and purple. The thing is, he hadn’t actually bothered to clean and sweep up the floor properly prior to doing this, so you could see all these cigarette butts that have just been painted over. I also shot a session outside with Syd, with his friend ‘Iggy The Eskimo’. I wouldn’t say she was his girlfriend, exactly – in those days, relationships just sort of flowed into each other. They were transient. Both Lindsey and Iggy ended up marrying bankers, I think.

“The car in the photo was a big US one which Mickey Finn, of Tyrannosaurus Rex when they weren’t T.Rex yet, had swapped for Syd’s Mini. Those pictures I took were among my very first as a photographer.

“He was always very co-operative. I always think I had an easier relationship with Syd because I was an outsider – the people who freaked him out were actually the ones he’d grown up with in Cambridge.

“As for Syd’s decline, well, I must say, I knew people a lot weirder than Syd, people who went into an acid decline and never came back. The secret, I learned eventually, was to unravel, through yoga, meditation. But Syd never quite did. Syd wasn’t just a straight acid casualty, acid was just what pulled the trigger. There’s a U2 song, ‘Stuck In A Moment You Can’t Get Out Of’, and that always reminds me of Syd.

“I later got to know David Bowie, and I think there are interesting parallels between the two. Both sang like Englishmen in an era awash with phoney transatlantic accents. Bowie worshipped Syd. He always saw him in the same bracket as Iggy Pop and Lou Reed, two other people who made music the like of which you’d simply never heard before. As for Bowie, he was physically as fragile as Syd, but psychologically a lot more resilient, which enabled him to have the sort of career he’s had. Syd could never have done that.

“I guess the fascination with Syd was that he got off the bus and never got back on again. Who else did that? Well, there was Peter Green of Fleetwood Mac, but he wasn’t beautiful like Syd and eventually he had the temerity to make a comeback. Syd made those two albums, plus a bunch of other unreleased stuff which came out on the Opel album and then never did another thing. It’s amazing that such a slender body of work has produced such an enormous influence. I understand there’s going to be a Syd Barrett movie now.

“I actually did the last interview with Syd Barrett in 1971. It was just half a page, plus a photo. Syd talked about how he was ‘full of dust and guitars’. He said all he’d really wanted to do was jump around and play guitar. The whole superstar thing was never part of the plan. He also said, ‘I don’t have a sense of humour. All I do nowadays is interviews and I’ve become good at it.’ Well, I’m not so sure about that…

“I still saw Syd a few times after that when I moved to London. He popped round, about four, maybe five times, just turn up on the doorstep. We’d have a cup of tea and a laugh. He was just trying to make up his mind, really, about getting off the bus.

“I never had any personal contact with Syd after that. But then, in 2002, when I was producing my book, Psychedelic Renegades, Syd agreed to sign a number of copies. He didn’t sign them ‘Syd’, which, of course, wasn’t his real name. He was back to Roger by then. I like to think that the reason he agreed to sign the books was because he liked my pictures and retained a lingering affection for me.

“Funny, really, how Syd never really left Cambridge, never really left England particularly. He returned to the house he grew up in, living like this mad uncle upstairs, occasionally floating down. Eventually, his mother died and it became his house. He would probably have ended up making a few million in those last years. I don’t believe he ever spent any of it. A bizarre, brilliant and beautiful man. And those photos I took of him set me on my way. I looked at them and thought: ‘This is what you’re supposed to be doing.’”