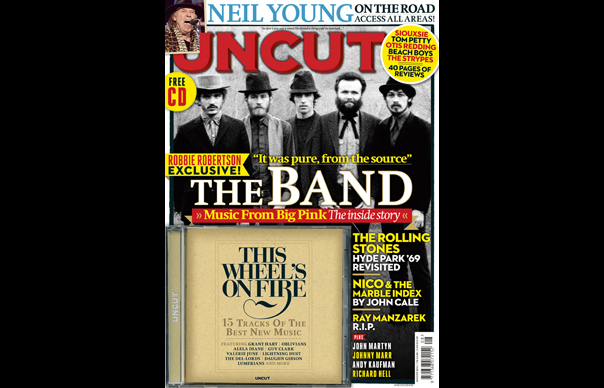

We pay tribute to the late Ray Manzarek in the new issue of Uncut (dated August 2013, and out now) – in this archive piece from Uncut’s September 2011 issue (Take 172), Manzarek, Robby Krieger, John Densmore – the latter pair now reunited in the wake of Manzarek’s death – Jac Holzman and more look back on the making of LA Woman, and the final days of Jim Morrison. “The damn thing,” says Ray Manzarek, “just rolls and rolls…” Words: David Cavanagh

_____________________

Nobody can remember the precise reason why The Doors flew 1,500 miles east from Los Angeles in mid-December 1970 to play two shows in Texas and Louisiana. It might have been because their manager, Bill Siddons, was best friends with a promoter in Dallas. Or perhaps The Doors wanted to discreetly try out a new setlist, and Jim Morrison suggested New Orleans, adding Dallas as an afterthought. Who knows? But whatever the reason for the gigs being booked, everyone remembers the outcome. They were Morrison’s tipping point.

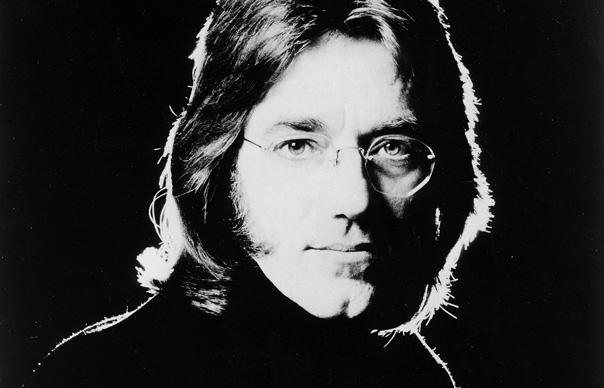

“Dallas was actually pretty good,” relates drummer John Densmore. “We played ‘Riders On The Storm’, which we’d never done before, and it went down really well.” But in New Orleans the following night (December 12), the vibrations were very different. The venue was a ballroom on the banks of the Mississippi, described by keyboardist Ray Manzarek as “a dark, strange, voodoo-filled place… an ancient building possessed by the spirits of dead slaves”. Morrison, depressed by his Miami trial in September (and its guilty verdict in October), was in a dark, strange place himself. An overweight, heavily bearded alcoholic, he faced six months in a Florida prison – with hard labour – for indecent exposure and profanity at the infamous Miami concert in 1969. He was currently free on licence, waiting to learn if his appeal would succeed. His 27th birthday (December 8) hadn’t been much of a celebration.

Onstage in New Orleans, during the obligatory “Light My Fire”, it became clear that Morrison had a problem. He sat dejectedly on Densmore’s drum riser, repeatedly missing vocal cues, before rising to his feet and angrily smashing the microphone stand against the stage until it broke. Finally he stormed off as the audience watched in silence. He never performed live again. Today’s equivalent might be Amy Winehouse, a singer who seems equally trapped in a fame bubble and an addiction vortex. Winehouse, of course, hasn’t delivered an album in five years. Morrison, by contrast, began making LA Woman – that most feline of she-creatures that stalk rock’n’roll’s midnight alleys and freeways – within days of his New Orleans meltdown. The Doors completed the LP in a whirlwind fortnight, and by February Morrison was gone from their lives forever.

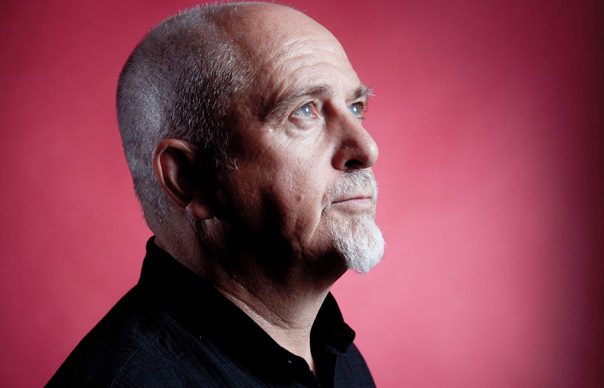

On July 3 this year, Ray Manzarek and Robby Krieger lit candles at Morrison’s grave in Père Lachaise, the ‘poets’ cemetery’ in Paris where Wilde and Balzac are buried. Krieger, guitarist and songwriter in The Doors, joined Manzarek onstage that night at the Bataclan theatre, performing “LA Woman”, “The Changeling”, “Hyacinth House” and other tracks from the classic album they recorded 40 years ago. Ray and Robby’s band has had various names since its 2002 inception, including D21C, Riders On The Storm and Manzarek-Krieger. The one name they’d love to use – but legally cannot – is The Doors. If they do, they’ll face a lawsuit from their former friend and drummer, John Densmore.

“I call us The Doors,” Manzarek, 72, tells me. “‘Minus Densmore’, of course, we must always say ‘minus Densmore’. He’ll play with some other band, but not with Ray and Robby. The dynamic has shifted! The power structure has shifted!” This is how Manzarek speaks: emphatic, sarcastic, convinced of his own (sometimes disputed) version of events. Manzarek not only curates the legend of Morrison as leather-trousered oedipal deity; he’s also a philosopher for whom music is “a Zen-like ecstatic state where you become the New Man of the Future, the Nietzschean merger of Apollo and Dionysus”. But Manzarek’s also a realist. He believes the three surviving Doors should accept lucrative offers to use their songs in TV commercials. He imagines these having a spectacular effect on “born-again Christian households in Iowa, who’ll think the devil has entered their living-room”.

John Densmore, 66, is nothing like Manzarek. He’s calm, patient, implacably opposed to Doors songs being used in adverts (he vetoed a $15 million bid from Cadillac to use “Break On Through” a decade ago) and intriguingly pro-altruism. Densmore gives 15 per cent of his income to charity and thinks other musicians should do the same. Here’s Densmore on the likelihood of a Doors reunion: “Listen, if Jim comes back, I’m there. But don’t call it The Doors without him. Unless we can find a way to play for some cause, some benefit, and maybe ask Eddie Vedder. That’s something I would be interested in.” But Densmore’s been talking about a Doors benefit with Vedder since 2007, and it’s yet to happen.

Somewhere between Densmore and Manzarek sits Robby Krieger, 65, the epitome of laidback, so grizzly and inscrutable that he sounds like he’s chewing on a cigarillo in a scene from A Fistful Of Dollars. “For a long time I didn’t play The Doors’ music,” Krieger says slowly. “I was doing my own albums, my fusion music, my jazz stuff. But then I would sit in with Wild Child, and I’d forgotten how much fun it was to play those songs.” Wild Child are an LA-based Doors tribute band. Their singer, a longtime Morrison impersonator named David Brock, officially joined Manzarek-Krieger last year. “He’s spent his whole life trying to be Jim Morrison,” Krieger confides, and pauses, as if wondering why someone would do that.

And Morrison himself? The admiral’s son, the poet, the Lizard King, the cinema buff whose life became a Hollywood movie – a concept he would have found “hysterical”, according to his manager Bill Siddons – is still, in 2011, the subject of heated deliberation (he’s a genius; he’s a fraud), morbid speculation (he’s not in the coffin), exaggeration, confabulation and guesswork. Even the finest minds in Tinseltown couldn’t get him right. “The thing about the Oliver Stone movie, apart from the fact that a lot of incidents were out of synch,” says Siddons, “was that it only showed Jim the Asshole. It didn’t show Jim the Intellectual, or Jim the Funny, or Jim the Generous. This was a guy who could hang out with [LAPD chief] Tom Reddin and [actor] Laurence Harvey at the same time. He was an amazing person.”

The 40th anniversary of Morrison’s death followed on the heels of that of LA Woman. Due for a two-disc deluxe release later this year (see panel, p45), the famous album – loaded with FM rock staples dragged from the gut and the swamp – sees the three ex-Doors, for once, in agreement. They all treasure it. Manzarek defines it as “the root-core Doors”, and asks rhetorically, “How can you not love an album that has ‘Riders On The Storm’ and ‘LA Woman’?” It’s a reasonable question.

For Densmore, LA Woman “got us back to our roots. We’d started out in a garage in Venice, California and we finished up in a rehearsal studio – making LA Woman quickly, spontaneously, going for the feel.” Krieger: “We were all in the mood to play some blues. Jim was really into the blues at that point. The blues pretty much set the tone for the whole album.”

Morrison’s approach to LA Woman, as we’ll see, was different to other Doors recordings. Photographer and filmmaker Frank Lisciandro, a close friend of Morrison, is tempted to place LA Woman in a valedictory context rather than a musical one. “If you look at the 10 songs,” Lisciandro argues, “eight of them were written by Jim. Five of them have a strong ‘Goodbye, I’m getting out of here, things are about to change’ feel to them. There’s a thematic flow to the album. There’s no doubt that Morrison is saying goodbye to a city, to a culture and to the people who’d embraced him and thrust him into stardom.”

While The Doors made LA Woman downstairs in their rehearsal room, Bill Siddons worked in his office upstairs, dealing with the day-to-day dramas of America’s most controversial band, its singer’s drink dependency (Morrison could sink 36 cans of beer in a day), his unwillingness to tour, his imminent prison sentence, his fluctuating moods and his helter-skelter, unpredictable lifestyle. Siddons had managed The Doors since he was 18, and was still only 22. He describes the experience as “being like a kid trying to control a moving, pulsating blob in which anything can happen or change at any moment, and you never have any idea what’s coming next”.

Such was the context, the subtext, the reality of LA Woman.

_____________________

Jac Holzman, 39-year-old founder of Elektra Records, had signed The Doors in 1966 after being tipped to their potential by Arthur Lee. Holzman saw them four nights in succession at the Whisky A Go Go before he realised Lee might be right. Not the sort of man to interfere in The Doors’ private lives, Holzman did, however, sometimes make a tactful intervention in their music; he’d once forbidden Krieger to use a wah-wah pedal on a song. The band called him ‘El Supremo’.

Earlier in 1970, Elektra had teamed up with two larger companies, Warner Bros and Atlantic, in a move that radically improved its distribution in America and overseas. Elektra wasn’t a sales-driven, commercially calculating label, but, as it happened, The Doors were a group whose success could be relied on. “They were gigantic,” says Holzman, now almost 80. “Remember, this was a time when DJs were playing whole albums. They would play all The Doors’ albums. The buzz and recognition of the band was continuous. A new Doors album was going to be a huge event no matter what.”

For all that, Holzman hadn’t been a particularly big admirer of their 1970 album, Morrison Hotel, feeling they’d “gone back into their comfort zone… I was hoping for something more adventurous.” Early rehearsals for LA Woman at Sunset Sound Recorders did nothing to raise his expectations. Indeed, they presented him with a major setback. Paul Rothchild, the producer of the band’s records since 1966, who’d recently been working with Janis Joplin [Pearl] just prior to her death in October, seemed exhausted and disillusioned. When The Doors played him their new epic, “Riders On The Storm”, Rothchild put his head in his hands and said, “I can’t do this any more.” He left the rehearsal with an ungracious comment about “Riders…” and cocktail jazz.

Rock’s history books portray Rothchild as something of a chump for failing to spot the magnificence of “Riders…”, yet it was more complicated, more emotional, than that. After five Doors studio albums in four years (and a live one), Rothchild sensed he’d become an impediment, not a facilitator. He was a perfectionist, a “30 takes” man, and this was one time when The Doors needed imperfection desperately. If Rothchild had produced LA Woman, remarks his engineer Bruce Botnick, “it probably would have killed him sooner than the cancer that got him [in 1995]”.

Later that night, an emergency meeting was held in a nearby Chinese restaurant. The Doors returned, telling Botnick they wanted to co-produce the album with him. Instead of using a top-dollar recording studio, they intended to record in the rehearsal room of their office building, The Doors’ Workshop (on the corner of La Cienega and Santa Monica Boulevards), where a clubhouse atmosphere prevailed and there was a pinball machine. “It was a place where they could come and go with zero pressure,” notes Siddons.

Botnick, 25, immediately made a suggestion. He’d been engineering an album by Marc Benno, a singer who’d had a duo with Leon Russell in the ’60s (The Asylum Choir) and was now making solo records for A&M. The bassist on Benno’s LP was Jerry Scheff, from Elvis Presley’s renowned TCB Band. Botnick: “As soon as I said that, Morrison’s ears pricked up. ‘Oh, I’d like that! Elvis’ bass player!’” Besides hiring Scheff to add muscle to the rhythm section (The Doors, of course, had no bassist), Botnick brought in Benno as a rhythm guitarist, giving Krieger the freedom to concentrate on his idiosyncratic lead lines. The Doors, that angular foursome with the unorthodox Spanish-rock sound, were now a reinforced, souped-up sextet.

Botnick liked the new tracks he was hearing, but Holzman hadn’t been privy to any of them. For Holzman, LA Woman was a step into the unknown, and a risk he was happy to take. “I trusted the band,” he says, “and I trusted Botnick, who I knew had done a lot of the important production work on Love’s Forever Changes. I thought The Doors would be in good hands. But that doesn’t mean I wouldn’t have rubbed a rabbit’s foot if I’d had one.”

The Doors made one demand of Holzman. They insisted that he stay away from the recording sessions. Physically, this was not easy; Elektra’s offices were directly across the street from The Doors’ Workshop. Holzman stuck to the bargain and didn’t cross the road once.

_____________________

One might be excused for supposing that Morrison wouldn’t have been ready, wouldn’t have been in a proper psychological condition, to undertake the exacting, often stressful processes of making an album of new Doors music. In photographs onstage in Dallas (December 11, 1970), he looks obese, apathetic and dog-tired. “He got a pot belly and went from 150lbs to 180lbs,” says Siddons. “He lost the ‘cat’ body that he’d had. We all thought it was intentional. He never wanted to be a sex symbol; it just happened. All of a sudden he was answering to a monster that he’d created, and he went, ‘Fuck this.’” In the months since the Miami trial, John Densmore recalls, Morrison had “seemed more serious and quiet”. Holzman, today, while brushing away the arrest and trial as “a set-up”, also admits that he expected LA Woman to be The Doors’ last album. “I sensed a finality about it. Growing his beard and getting [fat] was a pretty obvious statement.”

Fewer than 10 people witnessed the recording of LA Woman, including the musicians who made it. Among the most persuasive – and surprising – testimonies are those of Frank Lisciandro (who attended the sessions as a photographer) and Bruce Botnick, the co-producer. Lisciandro assures us that Morrison, far from reluctantly going through the motions or struggling to stay focused, had a wonderful time and was the principal cheerleader for the music they were making. Lisciandro: “He was the most relaxed I’d ever seen him in a studio. He was in an optimistic mood. I think the absence of Paul Rothchild gave him an opportunity to step forward as a bandleader.” Botnick found Morrison a “prince” to work with. “There were no drugs, no women, no sycophants,” he says. “Jim still liked to drink, and there was plenty of beer around, but he wasn’t drunk. He was extremely creative and he really led the sessions. And since he was staying at the Alta Cienega Motel right across the street, he was usually at [the Workshop] before we were.”

Morrison was in a long-term relationship with 24-year-old Pamela Courson, the girlfriend who would accompany him to Paris. Because Morrison had a tendency not to talk about women behind their backs, it was difficult to gauge how the relationship was going. “She was a constant force in his life, but they were completely volatile,” explains Siddons. “You never quite knew whether they were together or not. They’d taken a house on Verbena Drive and were attempting to live a domesticated life, but that only lasted a few months. That’s why Jim was living at the Alta Cienega Motel.” If nothing else, Morrison’s life in early 1971 was a perfect triangle. The Doors’ Workshop here. Elektra Records there. The motel there. And if you wanted to make it a quadrilateral, you could add the topless bar that he liked to drink in, right here. Morrison seems to have found the geography conducive to writing; motels and topless bars both feature in LA Woman’s title track.

The three surviving Doors, too, can confirm that Morrison was the driving force, as well as being a lot of fun, during the LA Woman sessions.

Densmore: “You ask how we handled him. He didn’t need handling. He sang most of his vocals in one or two takes. He really rose to the occasion.”

Manzarek: “This was a man who was beginning to wear down, but you can’t tell that from his singing.”

Krieger: “He would sing in the bathroom. We had a bathroom in the studio, where Jim was isolated, so we could take his vocals out later and redo them if we had to.” (Actually, as Botnick points out, they couldn’t. “He was leaking into the other microphones.”) The bathroom had no door, so Morrison was visible and actively involved in each take. The room itself was not large – Botnick estimates it at 20 feet by 12 – and had to accommodate five musicians, Densmore’s drums, two guitars and their amplifiers, a piano, a Hammond B3 organ, a Fender Rhodes, a Wurlitzer, a Farfisa and a pinball machine. “It was tight,” says Botnick. “It was like sardines.” No wonder the songs sound like sweat is dripping down their backs.

LA Woman took little more than a week to record. That included ‘Blues Day’ – the day when they tackled “Cars Hiss By My Window”, “Been Down So Long”, “Crawling King Snake” and other blues songs that didn’t appear on the finished album. Morrison, almost free now, was close to reaching the formal end of his Elektra contract with The Doors, which he’d signed at the age of 22. There was something he wanted to tell the others – the cause, no doubt, of the “optimistic mood” that Lisciandro mentioned earlier – but in the meantime, he made his final contribution to LA Woman; his last act as a rock star.

“There’s a whisper voice on ‘Riders On The Storm’, if you listen closely,” says Manzarek, “a whispered overdub that Jim adds beneath his vocal. That’s the last thing he ever did. An ephemeral, whispered overdub.”

_____________________

Paris. City of culture, city of exile. City where Hemingway had his heroic adventures in A Movable Feast. Where TS Eliot and Ezra Pound edited The Waste Land. Where James Joyce published the first edition of Ulysses. Where Gertrude Stein met Alice B Toklas on the latter’s first day on French soil, and quickly whisked her round to Picasso’s studio nearby. Paris: city where poets are put on pedestals, not on trial.

When Morrison broke the news in February that he and Pamela were moving to Paris, it was not the first seismic event to happen to The Doors that month. Nerves were still a little frayed from a 6.6 earthquake on the first day of mixing (February 9), which originated in the San Fernando Valley and caused the 30-foot wall of glass in the studio to sway alarmingly with every aftershock. Morrison’s thunderbolt was less destructive than an earthquake, but each of The Doors had his own view of what it portended. Densmore: “He said, ‘I’m going to get away.’ We said, ‘All right, we’ll see you in a few months.’” Krieger assumed that Morrison would return to make further albums with the band. (“We even started rehearsing new songs while he was away, for him to put lyrics to.”) Manzarek reasons: “The important thing is, he was going to Paris to ‘regain’ himself – to find the poet again. In Paris he could walk down the street unmolested. He was going to continue the line of American writers in Paris – Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Henry Miller – and I thought it was a terrific idea.”

But Bill Siddons is adamant that Morrison, whether he resurfaced in Los Angeles or not, would never have been a member of The Doors again. “He was done with music. He now wanted to pursue more formalised styles of writing – his poetry, obviously, and also to work on a couple of screenplays. He resigned from the band.” Morrison’s optimistic outlook suggests Siddons may be correct. Presumably, he was looking forward to leaving certain people, and certain habits, behind.

“Jim Morrison was going off on an adventure,” says Frank Lisciandro. “The fact that he’d honoured his contract with Elektra meant a lot to him. Remember, this was a guy with a lot of self-confidence. He’d recorded six albums. He’d self-published two books of poetry. He’d completed work on two films. He’d accomplished a lot in a very short time. He was going to Paris with his confidence soaring.”

From what we can surmise, no attempt at Los Angeles International Airport was made to detain him. Either he was not regarded as a fugitive from justice, or they neglected to notice him leaving. He probably didn’t bear much resemblance to his passport photograph anyway.

_____________________

Jac Holzman finally heard LA Woman when Botnick and Siddons invited him across the street for a playback. He brought a notepad with him, as usual, to write down critiques. “Everybody was there except Jim,” Botnick recalls. “We played it upstairs in Bill’s office. When it was over, Jac looked at his notepad and it was empty. He closed his eyes, took a deep breath and said, ‘I’d change nothing.’” Holzman recalls being “absolutely amazed… overjoyed… probably a little relieved, too, but mainly overjoyed and amazed”.

Siddons: “Jac gave the ultimate analysis of the record. He said, ‘Well, “Riders On The Storm” will be one of the biggest progressive radio tracks of the year, and “LA Woman” will become a standard, but the hit is “Love Her Madly”. El Supremo predicted everything that would happen with the record.” Indeed, “Love Her Madly” charted at No 11 in America, with tons of airplay coast-to-coast, giving The Doors their biggest hit since “Touch Me” in early 1969. LA Woman followed “Love Her Madly” up the charts, selling 500,000 in six months. It was all the more remarkable since there was no Doors tour – and no Morrison interviews – to promote it. “If it was going to be the last Doors album with Jim,” says Holzman, “it was a hell of a good one to end on.” Morrison phoned from Paris several times to check on its chart position. He sounded excited. But he warned Siddons and Densmore that he wasn’t planning a return to LA for the foreseeable future.

Morrison shaved off his beard in Paris, and, according to some accounts, lost weight. He also, Manzarek believes, became addicted to cognac. There is speculation that he and Courson snorted heroin together. He wrote poems and even recorded some sloppy music at an inebriated session in June (bootlegged as The Lost Paris Tapes). A couple of weeks later, Siddons received a troubling phonecall asking if it was true that Morrison was dead. Siddons phoned Courson at their apartment. She didn’t answer. Siddons: “I called her every hour until noon, when finally I spoke to her. She tried to say that Jim was OK and couldn’t come to the phone, but I said, ‘No, I’ve heard that there’s a serious problem, and if there is, I can get on a plane and be there for you.’ She broke down and agreed. I went straight to the airport and caught the next flight to Paris.”

Siddons arrived at the apartment at about 8.30am. “The casket was in the house. That was unsettling. I have a very clear visual memory of an oak casket that had 12 big one-inch bolts all around it. It was sealed closed. Put it this way, it didn’t invite me to lift it up and see if he was in there. It never occurred to me that I had a professional duty to open it. I knew Pamela well enough to know that Jim was dead. Then they came over and picked up the coffin, and we went to the funeral, and I came home. I remember landing and going straight to [publicist] Bob Gibson’s apartment to write the press release.”

The official cause of death was heart failure, which Siddons has never had a reason to disbelieve. Morrison was 27. Siddons’ business manager had a heart attack the following year, aged 29. But since Courson’s death from a heroin overdose in 1974, and particularly since the publication of Danny Sugerman and Jerry Hopkins’ No One Here Gets Out Alive (1980), it’s become common practice to overrule the medical examiner and attribute Morrison’s death to heroin – and, naturally, to add the lurid detail that he breathed his last in a bath-tub. Unless, of course, you believe that he’s not really dead at all. This, in itself, is virtually an industry in Morrison lore. Over the years Manzarek has alluded coyly, and not so coyly, to a theory that Morrison may have faked his death. “Ray has a creative mind,” says Siddons ironically, “and I think there’s a conscious effort on his part to keep the myth alive. I always thought it was completely tasteless.”

Back in LA, stunned, The Doors chose to soldier on as a trio, with Manzarek and Krieger sharing vocals. Holzman, unwilling to abandon the flagship group that had put his company on the map, re-signed them for three albums. The first was Other Voices (1971), released – incredibly – while “Riders On The Storm” was still in the charts. The trio had recorded some of it before Morrison’s death. “It was even a similar experience to making LA Woman,” says Botnick, who co-produced. “We made it in the same place, in exactly the same way. We figured if it worked once, it would work twice.” Reviews were encouragingly non-hostile; the trio played Carnegie Hall to some acclaim; and Holzman remembers Other Voices selling 400,000 copies. Manzarek feels the songs had merit (and many Doors fans agree) but the package somehow couldn’t withstand the glaring absence of Morrison from the picture. “The image of the three Doors wasn’t appropriate,” Manzarek admits. “It needed four.”

Other Voices was followed by Full Circle (1972), whereupon The Doors moved to England and began a search for a singer. Howard Werth from the progressive-rock band Audience was among those approached. “I did some rehearsing with them in a summer house down by the river. Jim Morrison’s name wasn’t mentioned at all. All I could get out of Ray Manzarek was that Morrison had died of a drug overdose.” Elektra gently pulled the plug. The three Doors weren’t getting along. Manzarek yearned to play jazz; Krieger and Densmore wanted to persevere with rock. Manzarek flew home. Krieger and Densmore added a Jamaican bassist (Phil Chen) and a soul-rock singer from the Midlands (Jess Roden), renaming themselves The Butts Band. They played no Doors songs in their setlist. “Robby was the main songwriter,” Phil Chen remembers. “I don’t think we were living in the shadow of The Doors. That time had already passed.”

This was true. Even with two ex-Doors in the lineup, The Butts Band rarely rose above club-sized venues. In London they were booked at the Fulham Greyhound on the pub-rock circuit. In New York, where Krieger and Densmore had headlined Carnegie Hall two years earlier, The Butts Band graced the fading days of Max’s Kansas City.

By 1974, The Doors were history.

_____________________

Uninvolved with the ex-Doors’ careers since the early ’70s, Bill Siddons was brought back in 1978 to oversee an LP called An American Prayer, which consisted of Morrison poems set to music by Manzarek, Krieger and Densmore. Siddons was unprepared for the reaction that followed. Not only did his daughter start asking for photos of Morrison to distribute among her schoolfriends, but the voice of Morrison and the music of The Doors thrilled journalists and radio presenters at playback parties in 22 American cities. “We gave them a glass of wine, cranked up the album and they all walked out of there saying, ‘Oh my God, this was the greatest band ever.’ The next day, they started playing Doors records on the radio again.”

Though the LP cover shows him bearded and rugged, Morrison was introduced to a new generation of fans as a lithe, panther-like poster boy with his chest bare and his gaze steady. Candle-lit teenage bedrooms resounded once again to “The Crystal Ship” and “The End”. Then came the biography, No One Here Gets Out Alive, authorised by the band, with input from Manzarek. Extraordinarily popular, with a riotous anecdote on virtually every page, it captured Morrison as an obnoxious, defiant, foul-smelling force of nature with voracious alcohol and drug appetites. Frank Lisciandro, appalled by the sensationalist tone, calls it ‘Nothing Here But Lots Of Lies’. However, the book undoubtedly boosted the revival of interest in Morrison and The Doors. By mid-1980, when Siddons left again, he estimates their business had “sextupled” since the mid-’70s. He adds, “And it’s never abated.”

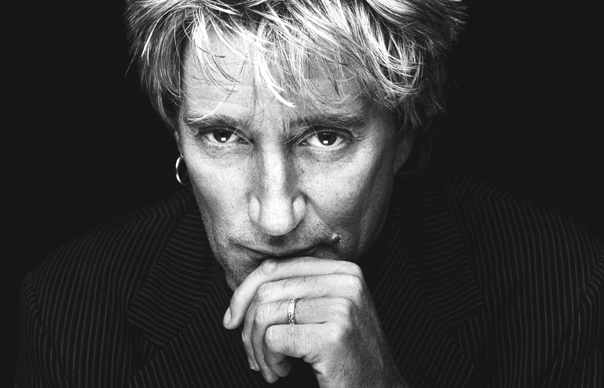

Phil Chen, ex-Butts Band, is now the bassist in Manzarek-Krieger. They perform, he tells us, to audiences of all ages, including original Doors fans in their fifties and sixties who don’t seem to mind Morrison (or, for that matter, Densmore) not being there. Chen has a good theory about this. “What happens is, classic rock never dies. If somebody dies in a group, it’s sad, but it almost doesn’t matter. You just find a replacement, ’cos the people go for the music. We played in Mexico and there were 20,000 young kids singing all the lyrics. They’d learned them from their dads. Those Doors songs will last forever. They’re not just the music of yesterday.”

Is it a full-time job being a custodian of The Doors’ legacy, I ask Manzarek? “No, no, no,” he replies. “The stone rolls of its own momentum. The damn thing just rolls and rolls. I have a grand time with it. It was a marvellous band – a literate, jazzy, poetic rock’n’roll band – and it accomplished what it set out to do.”

And still does, lawyers permitting?

Manzarek scoffs: “Look, Densmore has his version of ‘selling out to the man’. We are the man. The Doors are the man. If we have the courage to control the universe, we can! The destiny of America belongs to those who have the courage to seize it!”

As to how Morrison might have interpreted a mind-boggling statement like that, it’s fair to wonder if he’d feel something had been irretrievably lost, not courageously seized. He is, it seems, the ghost in everyone’s thoughts, dissolved but unforgettable, still communicating in ephemeral whispers to those who can hear him.