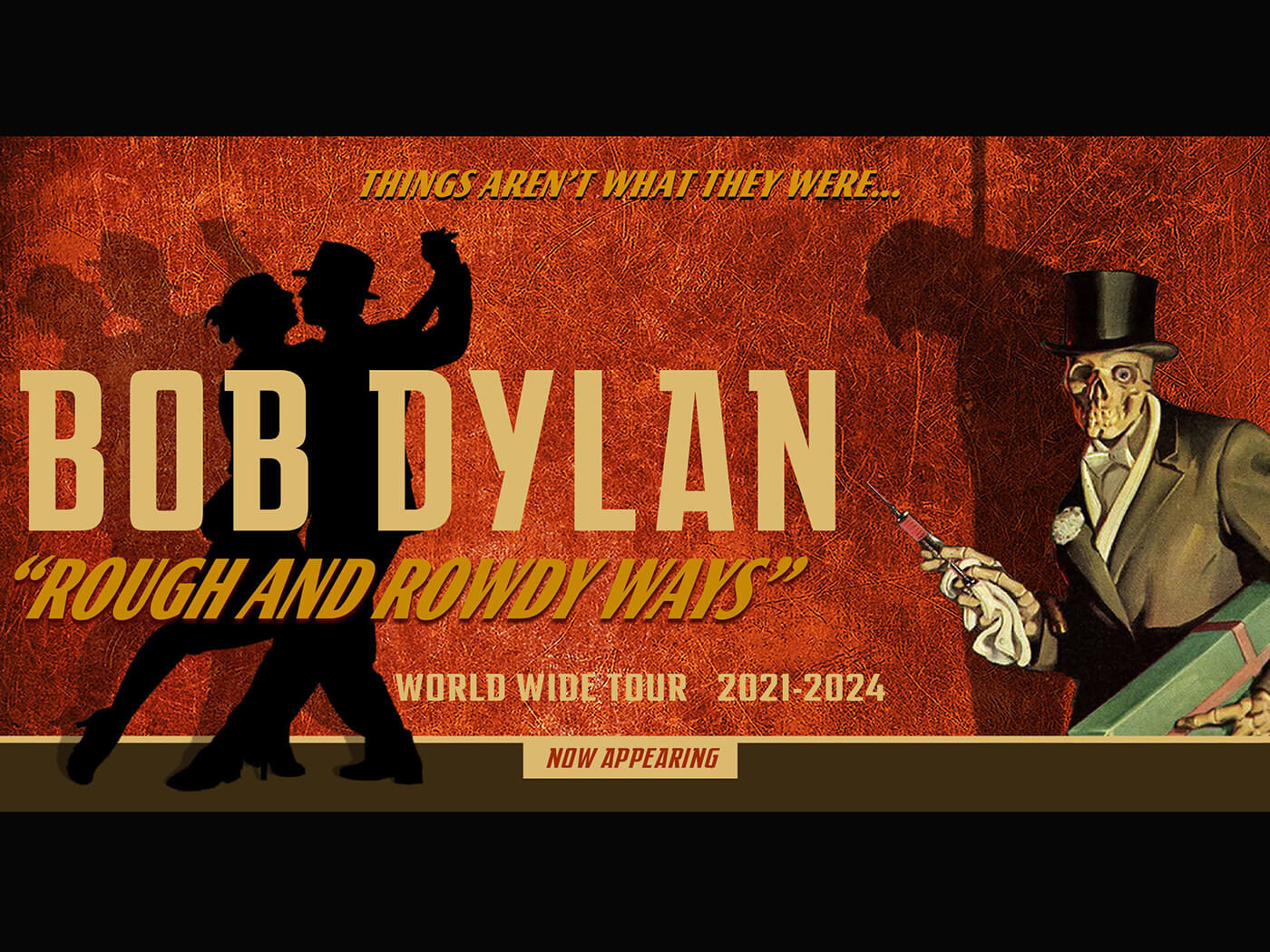

It’s Hallowe’en night in the city. A well-dressed skeleton offers you a syringe. The floor starts to glow. It’s shadow hour dream time, with your host, Bob Dylan.

On the second night of the Rough And Rowdy Ways tour’s spooked and spiritual mini-residency in Glasgow, as the rainy streets fill with costumed figures and flicker with the light of scattered pumpkin lanterns, it’s hard not to think about the most famous Hallowe’en concert Dylan has played, back on October 31, 1964, at New York City’s Philharmonic Hall, a landmark performance that became a treasured bootleg, eventually canonised with official release as part of the Bootleg Series.

Stepping out with an acoustic guitar and harmonica, Dylan, twenty-three years old, and moving fast, proceeded to stun his audience with a concert that included a fistful of fresh-minted songs that travelled in directions no one expected. Long compositions that dealt disturbing visions in complicated patterns of words, hails of imagery both pointed and opaque, stabbing and tender. Songs that existed in their own space, yet seemed uniquely suited to the rising turbulence of the world outside, delivered with a concentration that took the breath away.

After one, “Gates Of Eden”, he reassured the crowd: “Don’t let that scare ya. It’s just Hallowe’en. I have my Bob Dylan mask on. I’m masquerading…”

Flash forward exactly fifty-eight years later, and, well, to quote the lyric from “I’ve Made Up My Mind To Give Myself To You” that serves as strapline on the tour poster, Things Aren’t What They Were. Except, well, maybe some things are.

Dylan, accompanied by his immaculate five-piece band all dressed in black – all the better to become pure shadow when the stage lights drop and the towering Black Lodge curtained backdrop blazes up like a wall of fire behind them – is no longer the solo troubadour, and no longer 23 years-old.

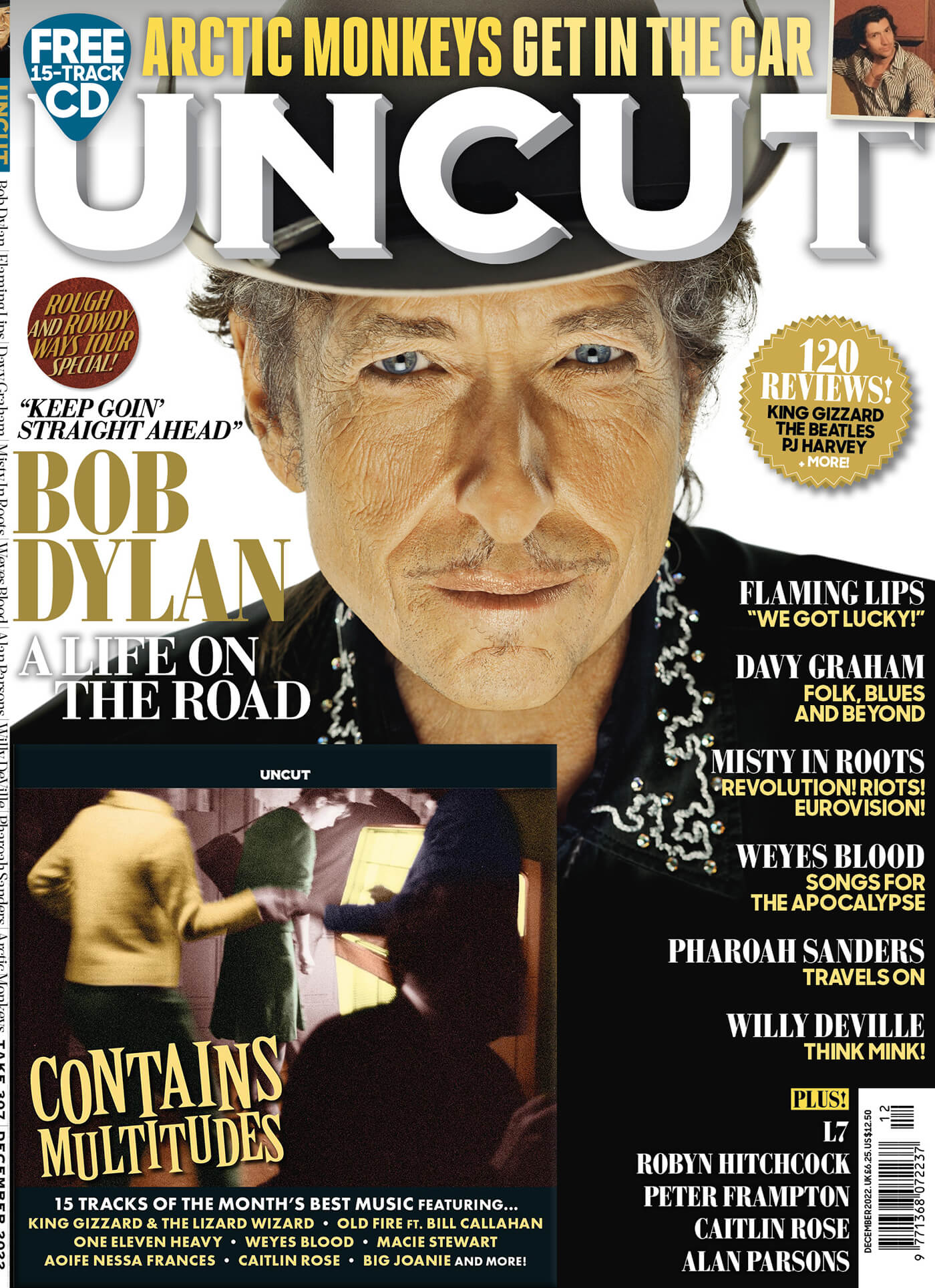

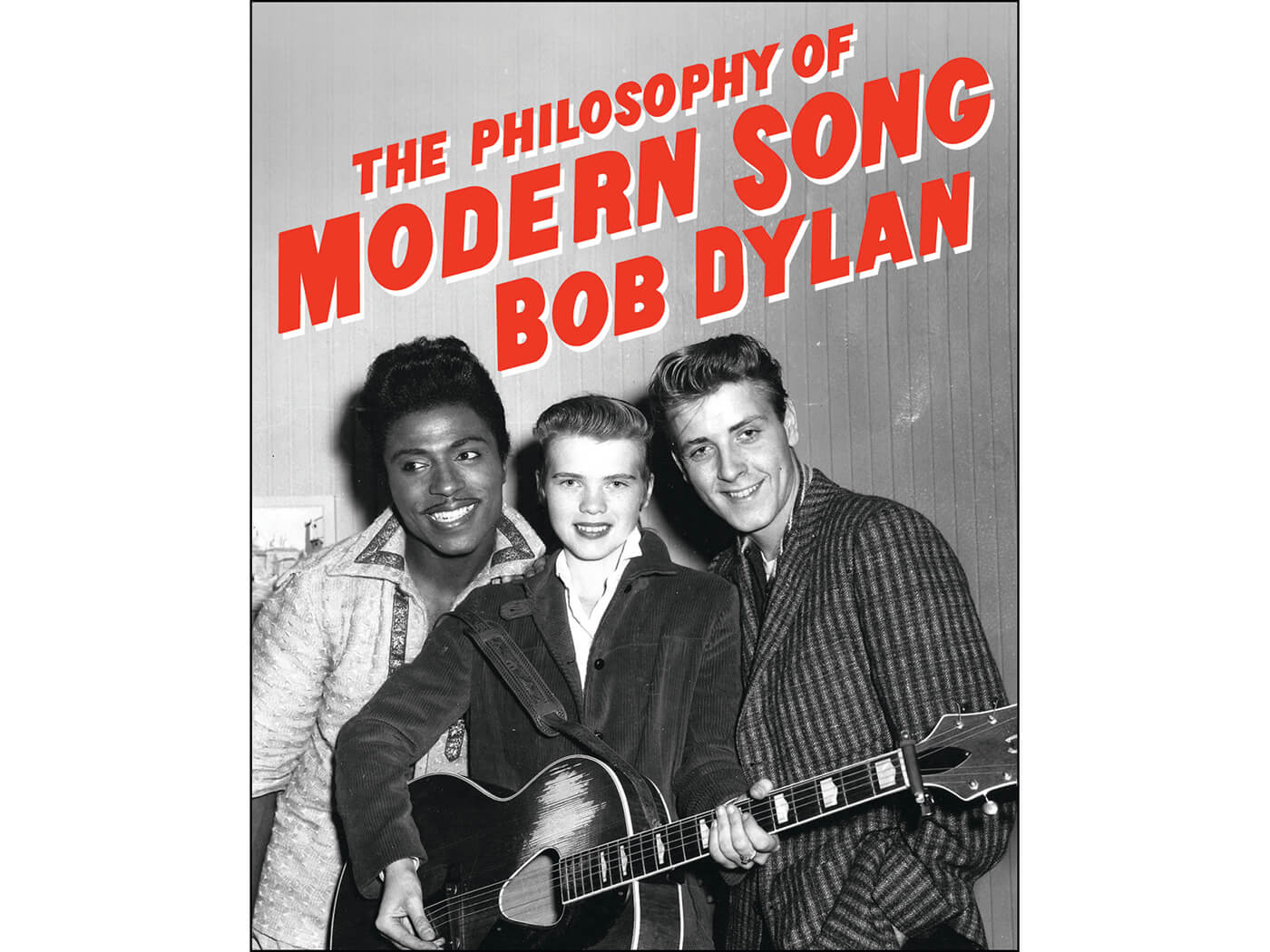

Yet here he comes. Still producing at a prodigious rate (this show comes on the eve of the publication of his new book, The Philosophy Of Modern Song, while the last year has seen the recording of at least an album’s worth of music in the shape of the sessions for the Shadow Kingdom film that saw him reworking chapters of his songbook.) Still energised most by the most recent songs in his repertoire, long, complex compositions that, tonight, build their own world. Still delivering them with a focus that is spellbinding.

Meantime, outside, the sense that the civilisation is still trembling on the edge of an abyss takes care of itself. “Y’know it’s Hallowe’en,” Dylan teases between songs in 2022. “All Saints’ Day. And–I–am–scared.” Then he leads us into a mesmerising version of “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)” that soothes any fear away for as long as it lasts. And it seems to last forever.

As he has been doing almost without variation, Dylan played the same set both nights in Glasgow. The first show, on Sunday, was entirely magical, but – maybe it’s the spirits loose in the air – the second feels like a step up, everything shifting into new focus.

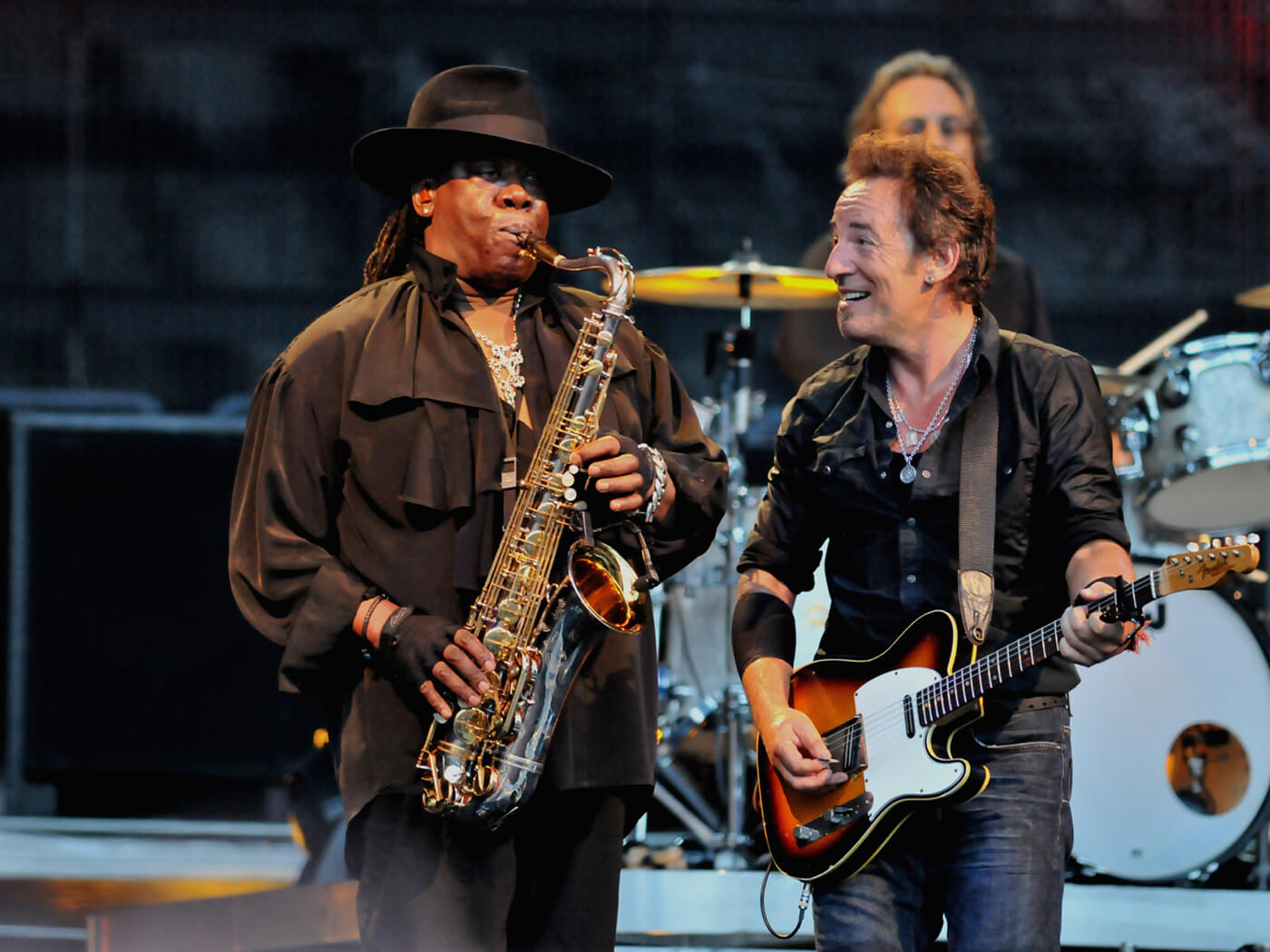

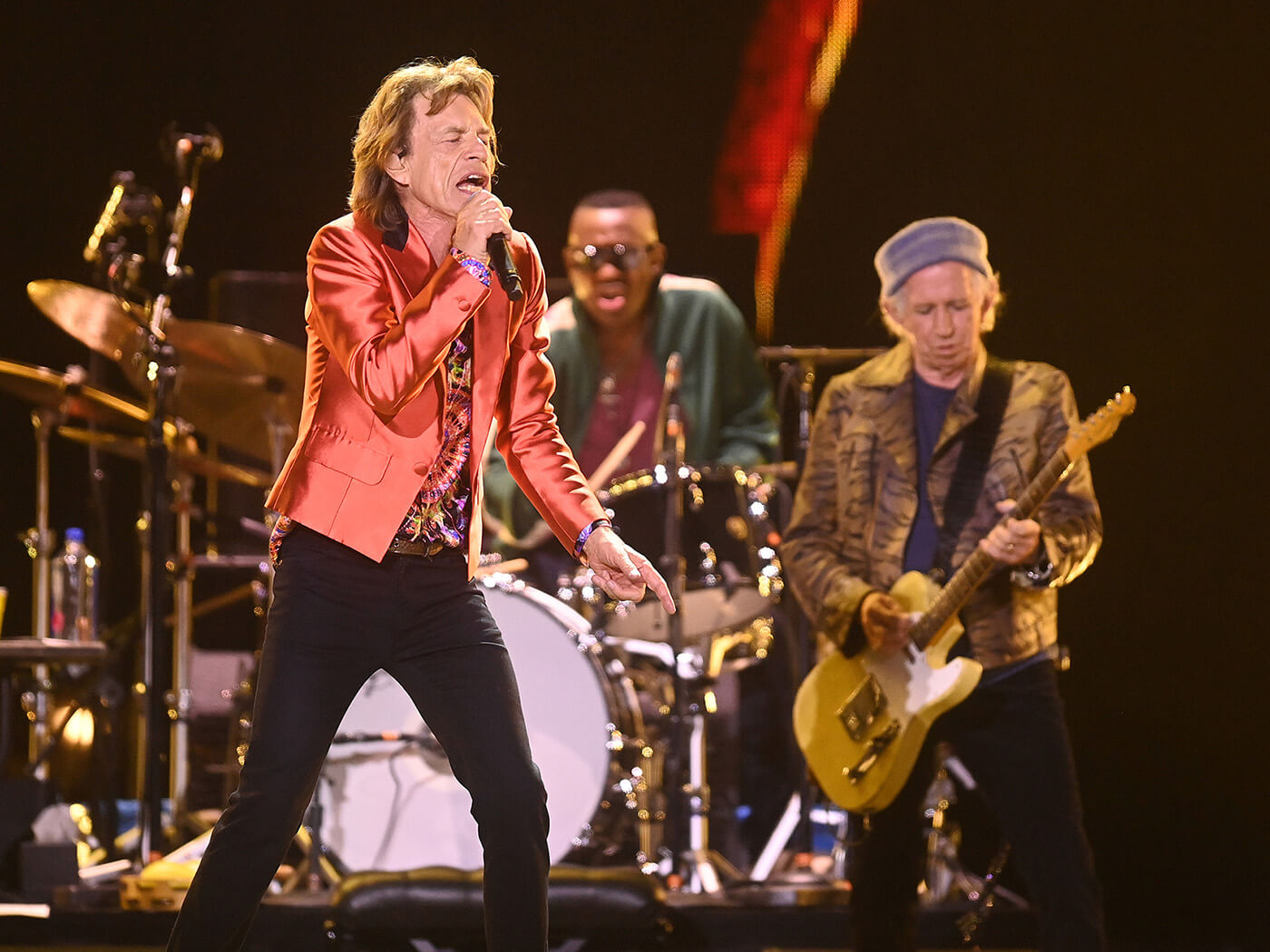

Where peers like The Stones can reproduce sets like a machine, Dylan always pushes songs in performance, handles them hands-on, so that rough edges and rowdy moments of uncertainty, or discovery, are still allowed. On Sunday, leading from behind his battered upright piano, that wilfulness saw the odd moment of discord as his extemporised piano lines sometimes bumped and crashed against the groove the band laid down. At one point, his determination to continually recast songs in different characters, different costumes, saw a freshly rearranged “Gotta Serve Somebody” almost fall apart. As the band took a stumble, Dylan stopped singing on the beginning of a line, stating and re-stating the beat on piano while the group leaned in around him, watching, listening, until everybody jumped back on it. Simultaneously, the stage lights went out off-cue, plunging the performers into disorienting blackness for an apocalyptic second.

On Hallowe’en night, though, they don’t simply nail this new “Gotta Serve Somebody”; they practically nail the audience to the wall with it, as guitarists Bob Britt and Doug Lancio lock into a ferocious twin guitar assault that hits like a thick, fuzzy tornado. Meanwhile, across the night, Dylan’s piano, whether he’s playing big, warm, gospel-soaked chords, baroque little filigrees, or spindly lines that slink like a jazz cartoon, doesn’t collide with the groove, but rubs against it, winds around it, like a cat. The first night he stepped out from behind the piano a few times to acknowledge applause. Tonight, he stays standing behind it throughout, a man at work.

His singing is different the second night, too. On Sunday, Dylan was in incredibly powerful voice – he sounds rejuvenated right now – but on Hallowe’en he switches tack, singing with the same sustained strength, but reining back, wielding it in softer, more tender, often more playful ways. He barks and bites when he needs to, but on “Key West” and “I Contain Multitudes”, he positively purrs. On “I’ve Made Up My Mind To Give Myself To You”, his singing is soft as breath, his piano touches glint like moonlight hitting water, and there’s no need to be ashamed if that’s a tear in your eye.

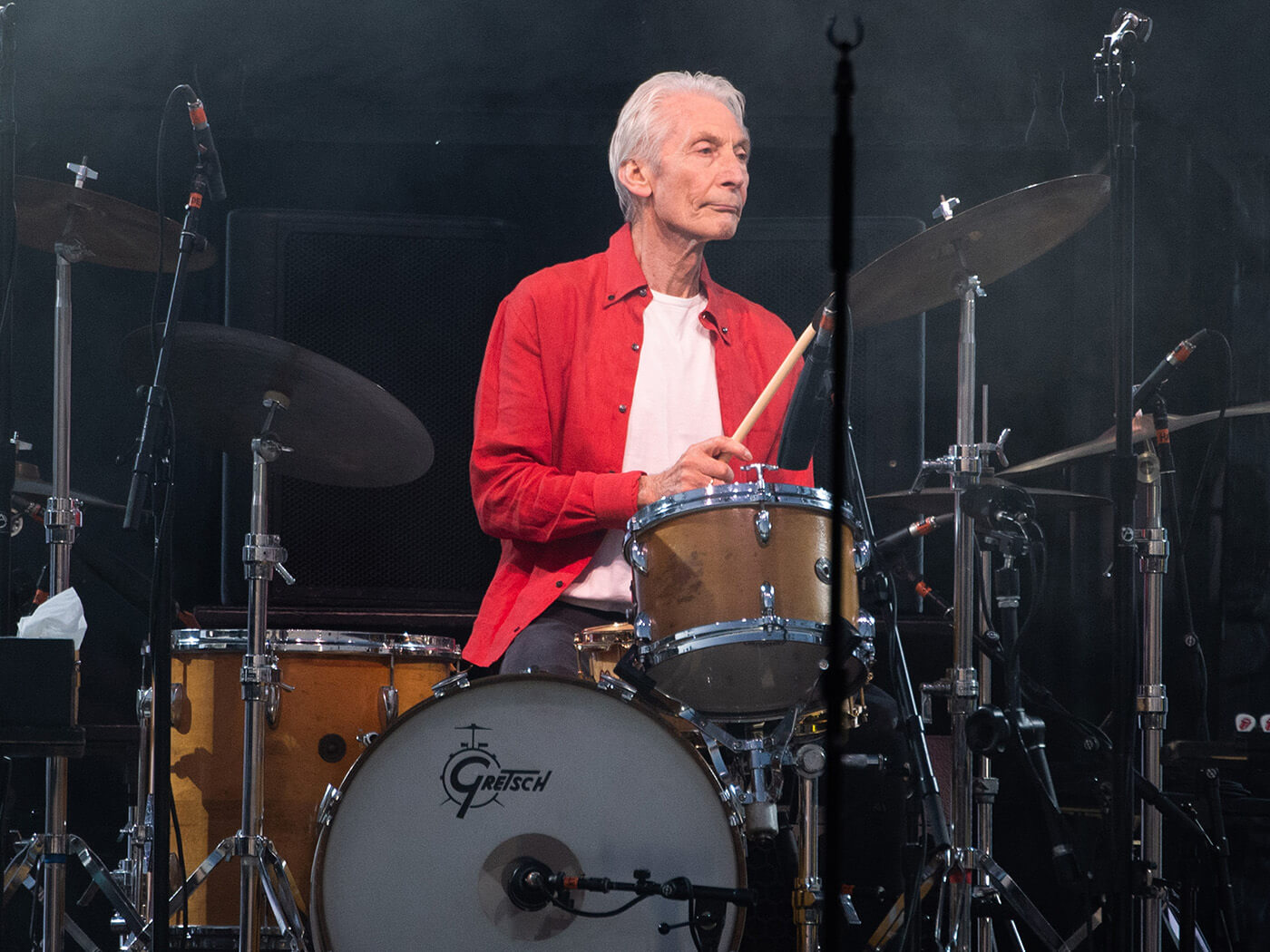

The changes Dylan made to his old songs for Shadow Kingdom influence these shows as much as the Rough And Rowdy Ways album itself, and tonight the curious combination of playfulness and sheer intensity of focus makes the new arrangements shine and glow. A lot of it has to do with the way his new drummer Charley Drayton plays – less pushing songs along than responding, commenting, or, when he rattles his shaker, sending an ominous shiver through them, a sound that creeps and ghosts around the auditorium like the spectre of a snake.

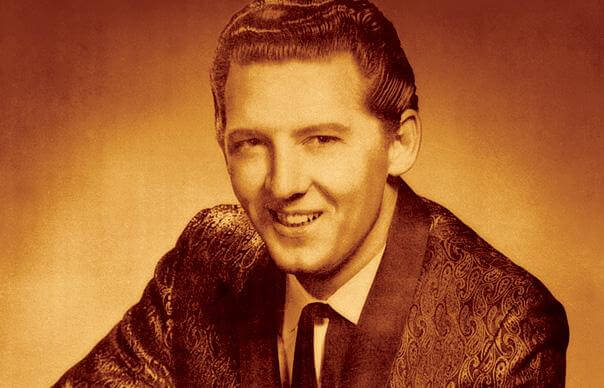

“When I Paint My Masterpiece” rolls out as a kind of Celtic riverboat piece. “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight” shifts through eras, beginning somewhere near 1967, before suddenly switching pitch into the stomping showtime go-go riff of Roy Head’s 1966 hit “Treat Her Right” – a song Dylan last played during a rehearsal for his sharp-sloppy punk appearance on Late Night With David Letterman in 1984. “To Be Alone With You” becomes a spry Appalachian hoe-down in an extended instrumental coda as Dylan’s piano gets into a long trade-off with Donnie Heron’s lilting fiddle.

Most telling, though, is how the newest songs continue to evolve. Some Rough And Rowdy tracks remain much as they were on the album, as with tonight’s perfect Hallowe’en one-two combination punch of the weird tales “Black Rider” (dark, stark, echoing) and “My Own Version Of You” (simply incredible).

But others have already moved on to different places. “False Prophet” has shed its original skin, based on Billy Emerson’s “If Lovin’ Is Believing”, and now comes sashaying out swinging its shoulders to a riff moulded after Little Walter’s “Just A Feeling”, continuing Dylan’s career-long entrancement with Walter. “Let’s go for a walk in the garden…darlin’” he winks, somehow finding room to fit yet another word in there. “Key West”, one of the great tracks on Rough & Rowdy, is perhaps most radically reshaped of all, almost a completely different tune now, and yet still beaming out from the same trancelike paradise zone on the horizon, and drawing you toward it.

As the stage lights burn pumpkin-orange around them, every song seems a highlight in a different way. Most poignantly, perhaps, when Dylan reaches the point where he stands Elvis Presley and Martin Luther King in line in his song of vocation, “Mother of Muses”. History sparks in strange ways as you recall Elvis singing Dylan songs, recall Dylan singing on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in 1963, just before King said, “I have a dream.”

All around these performances hangs the question of whether, after so many years, this is Dylan’s farewell to performing live. Is this the parting glass? The Ending Tour? When he gets to the night’s final song, “Every Grain Of Sand”, it’s hard to push that thought away, especially when, for the only time, he picks up his harmonica and blows out one final, wordless chorus, still sounding like Bob Dylan on harmonica, still a sound like nothing else.

The place just erupts afterward, and erupts again when, after they’ve made their exit, Dylan and the band return from the shadows to take one last bow, Dylan standing nodding as the roars and applause come long and hard, the crowd not wanting to let them go.

But after that, they’re gone. Dylan’s piano chair sits empty. As the lights come up, I overhear a women recall seeing him the first time he played Glasgow, back in the electric mist of 1966, when he was changing things, doing something new, moving fast. I had to wonder whether she had made it here in time for his final show in town, too. And yet, watching him still pushing, still working at it, still keeping his songs restlessly alive, still finding something new, he seems like a man who still reckons he has a lot of work left to do. Meanwhile, it’s just Hallowe’en, and, at the door on the way outside, one of the usherettes is standing smiling with a fake knife pushed through her head.