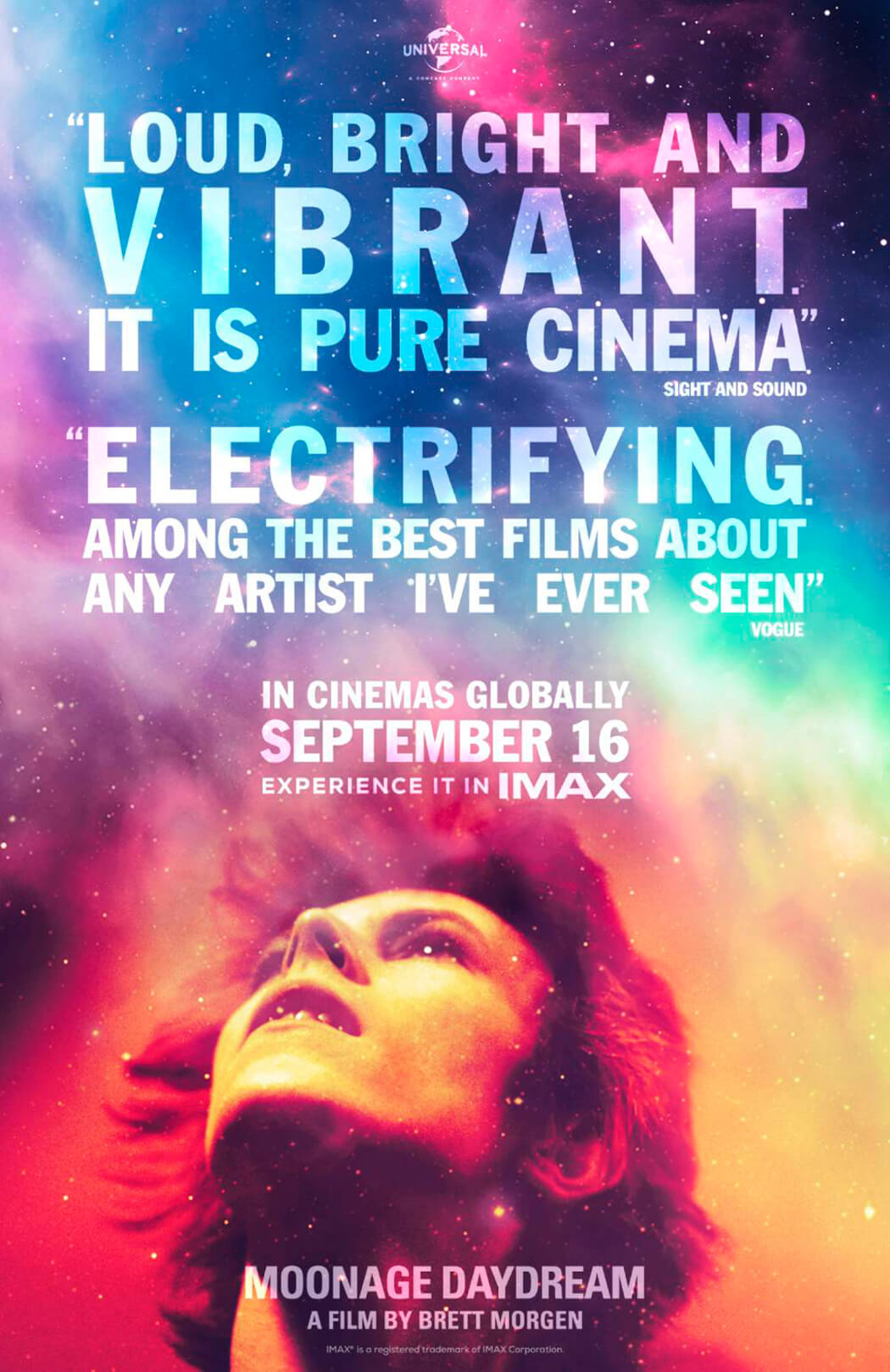

Moonage Daydream, Brett Morgen‘s documentary on David Bowie, is in cinemas now. You can read our review here, but in the meantime here’s Morgen himself on Bowie, revelations from the vaults and why there’s no Tin Machine in the film…

UNCUT: Where did you start with this?

BRETT MORGEN: I began with an idea for a type of film before I knew it was going to be on Bowie. But coming out of [the 2015 Kurt Cobain documentary] Montage Of Heck, I had been making biographical nonfiction films for 15 years. I had arrived at a point where I realised that what I really enjoy is this: sound, colour-correcting and editing. I have never really believed that movie theatres are great places for facts and information. I think movie theatres are a place to experience. I decided I wanted to try to create a kind of hybrid genre that I was calling, as working title, The IMAX Music Experience. The idea was that if I was to do something on The Beatles … Well, we all know they’re from Liverpool, we all know that they came to American and did Ed Sullivan, we know they went to India – why would I waste the real estate to try to explain that? You either know it or you don’t, and what difference does it make? But I would love to go sit in an IMAX theatre for two hours and be immersed in Beatles imagery and sounds in 12.0 audio like I’ve never heard it. So that was the sort of premise, and I was going down that road with several bands.

What happened next?

David passed. I had met with David in 2007, to discuss a kind of hybrid nonfiction film. At the time, he was in semi-retirement, so the timing didn’t work out. [After he passed] I called his executive Bill Zysblat and I mentioned the type of movie I wanted to make. Bill remembered me from our meeting nine years earlier. Bill also, I think, worked with The Rolling Stones – he was a fan of Crossfire Hurricane, my Stones film, and he said, “You know, most people don’t know this, but David’s an avid collector. He’s been saving everything, and over the past 25 years he’s gotten more interested in building the archives – but he never wanted to make a traditional documentary.” So right when they were thinking, “What are we going to do with all this stuff?” I came knocking on the door saying, “I want to do anything but a biographical documentary.” The more I got into it, the more apparent it became how David really lends himself to that sort of venture.

Where did all the material come from?

The estate provided me with access and digital copies of everything in the vault, so we brought in five million assets. We had an archivist who was working around the world collecting whatever the estate didn’t have from proper sources, like the BBC or what have you. Generally, when I’m starting a project, I have a process – I read every book there is on the subject. That’s really just so that when I look through the primary source material, I have some frame of reference or context. When I did the Stones film, I think it took … I want to say, like, two and a half months to screen through every piece of media in the Stones vault plus anything that we can find from 1963 to 1981. The Kurt Cobain film must have been like six or seven weeks, if that. I put four months in my schedule for Bowie. We built a production schedule for six, eight weeks around that. It took two years to screen the Bowie material. I essentially ran through the entire budget before we even started picture-cutting. I was planning to be a co-editor on the film but never intended to be the sole editor. While this was all happening, in 2017, I had a massive heart attack and flatlined for three minutes and remained in a coma for five days. It didn’t happen by accident. My life had no balance to it. I was a workaholic, my sense of self and self-worth was entirely wrapped up in my work. It was my first priority and it led me to a coma. The day I had a heart attack was my son’s birthday. I have three children: one was born on January 5, and one on January 8, David’s birthday, I had my heart attack on January 5 and I was in a coma until [January 10], one year to the day from when David died, and on my daughter’s birthday. When I came out of that … You know, you start asking yourself: ‘What is the meaning of my life?’ Because it could have ended right then. My son was only seven or eight, you know? What would he have remembered? What’s the thing that dad always used to say? The example that I had provided them with was: work really hard and you’re gonna die at 47. I had nothing else to really offer. It was at that time that I was ingesting David. So that clearly had, as you can see is evident in the film, a very strong impact on what materials were speaking to me. I knew David was an amazing artist and musician going into the project, but I had no idea what an amazing man he was, and how much wisdom he had. Then, at some point, I realised that, through David, I could create a roadmap for my children for how to live the most fulfilling life in the 21st century. That’s what the film would be.

How did you carve out that course?

As it turns out, as I continued scrolling through the two years of material, only one through-line appeared to me. It wasn’t like I saw several different possibilities. The through-line for David was this: transience and chaos. It’s what he talks about, in ’71. It’s what he talks about throughout his entire career. As you hear in the movie, as we approach the ’90s, he literally states, “My through-line is chaos.” So I took a sort of liberal interpretation of that, and I realised that transience, or chaos – whatever you want to make of it – can be loosely translated to be applicable to several different threads that are essential to understanding David. Like the gender fluidity. The William Burroughs cut-up process. Always being on the move, always searching. The lack of mobility, or searching, in the ’80s is when he actually becomes static. So it seemed like this could be a through line that connected all of the eras, and I then created a playlist, sort of like a jukebox musical. I took, let’s say, three songs from each album that in my mind had some thematic connection to that through-line and weaved together a playlist that would serve as a foundation – not that the audience would understand that all these songs are picked for this reason. It’s like an Easter egg. It’s a bonus, but you’ve got to assume no one’s gonna see it or get it.

What do you mean by that?

Well, first of all, I don’t think anyone even looks for a subtext in nonfiction. I don’t think it’s a thing, because people don’t think of nonfiction filmmakers as controlling the mise en scene. But even in fiction … I mean, I grew up as a massive John Ford fan and wrote essays, endlessly, about the subtext in John Ford’s films. My father, who also loved John Ford’s films, couldn’t write an essay about the subtext because it wasn’t something that he needed to enhance the experience for him. I always look at subtext like this – there’s two things happening: there’s the surface, and there’s what the director is working on underneath. But you cannot demand the audience see what’s underneath, so you always have to have a surface thread that’s more tangible. So – slowly, slowly – the film started to come together, the themes really resonated with what I was going through. There were a set of rules and guidelines that I created for myself to help me navigate the mission. I think that once I had the structure in place, then it started to get going. Having said that, getting to that point was difficult, but then executing it was incredibly challenging.

Why was that?

When the pandemic first started, before there were vaccines, I had a heart condition, so I could not be around anyone. I worked in total isolation. For really, for two years, I had no one to show any footage to. Because of security issues, we couldn’t send links to friends, and I couldn’t have anyone come into the building. I had no producers, I had no network execs or studio execs. So I was kind of like alone with this material. At a certain point, we had no money so I couldn’t hire another editor to help me out.

Why did you decide to start with ‘Hallo Space Boy’?

‘Hallo Space Boy’ was very deliberate. This film is does not fit into a genre. All films are part of a genre. Even if the genre is as broad as documentary-experimental. Genre gives you a compass. I was working in an ill-defined genre. So I had to create a set of covenants with the viewer very early on, so that they could understand this was not going to be a biographical film. It was not gonna be a chronological film. It’s not that type of film, and I had to get them sort of ready for what type of film it might be. So I opened the film with the quote about Nietzsche, which is really one of the core themes of the film. But, more importantly, the idea was that when you open a film that people think is going to be a musical documentary with a quote from Nietzsche, they won’t be expecting to see a scene where the artist hears their song on the radio for the first time. That was the first flagpole. As we travel through the lunar landscape, through the audio presentation, I was trying to send transmissions, little audio things, as we move through the 20th century. So we hear a little bit of Triumph of the Will. And then we hear “Inchworm”. Listen, nobody’s expected to know this, but it’s David’s favourite song when he was a kid. Then the soundtrack becomes very ethereal. You hear a line from Blade Runner. It’s all sort of floating out. Then you hear a little bit of strumming from “Space Oddity”. A few little notes from “Life On Mars”. At that point, I’m trying to kind of create a sense that there’s no backwards or forwards, no top or bottom, and you’re just getting these fragments. I’m preparing them. Starting with “Hallo Space Boy” was a really critical way to kind of announce that we’re not going to be chronological, and that if you only like early David Bowie music then you should leave.

There isn’t too much music from his later career…

I’ll come back to why the film doesn’t go too deep on the post-’95 stuff, for a very good reason. In my mind, at least. But in that sequence – and the use of clips, many of which are from films that David was inspired by – I’m not expecting the audience to know that those are films that David liked. At that point, all they’re really supposed to see is that there was something coming from above, something that is being willed by the people, and people are gathering for some sort of ritual, if you will. That’s the “Hallo Space Boy” sequence. To follow that, David comes out and starts doing “Wild Eyed Boy From Freecloud”. And then I cut to a shot of David at an airport in Southeast Asia wearing a blue suit and yellow fedora. See, I liked this idea that there is no backwards, there’s no forwards, there’s no up or down, and that David could be singing about himself, narrating the story of himself in the future, or in the case of “Rock’n’Roll Suicide”, in reverse function. So I threw those shots of David wandering around the escalators and all that during “Freecloud”, because “Freecloud”, to me, is about alienation and loneliness, and I liked the idea that David Bowie is singing about David Bowie. If you ever see the film again, there’s all sorts of little things in there. Like, David’s at the airport, and I threw a line in into one of the side speakers where someone shouts, “David!” and he turns his head on cue, and it brings you back into the concert scene. When he’s doing “Freecloud”, we added coughs, to make it feel like you’re in church. Obviously, you wouldn’t have been able to hear someone coughing in the in the arena. But the whole idea behind the first section of the film was, by design, to say, “I’m not gonna explain anything.” When you get to the Philip Glass section, which follows “Jean Genie”, that’s when I’m like, ‘OK, here’s the last piece of the puzzle that you’ll need to understand the movie.’

And what’s that?

That you’re not going to understand it. It’s all about the mystery. It’s not supposed to be explained. For example, I really wanted to just thrust the audience into Ziggy so that they could experience Bowie the way the public experienced Bowie when he came on television in 1973 with “Starman” and people were like, “What the hell is that?” So I wanted you to just be thrust into it. The other thing that was really important for me – and this goes back to the footage of him in the blue suit walking through the airport – was that I saw the Ziggy Stardust movie for the first time in ‘83, I think, when it was theatrically released for the first time. My memory of it was that it was rainy, foggy, out of focus and red. It was like kind of disappointing in a weird way, because I guess, in my mind, Ziggy seem so colourful. I did not want to be limited to that oppressive red palette, and so by bringing in blue and yellow into the predominantly red colour scheme, We were able to start to build out a rainbow. We then added purple and yellow hues where they didn’t exist, just making them sort of sparkle a little more. And one of the things that really thrilled me – which has nothing to do with the through-line or anything else – was that I wanted to bring Ziggy to life. I wanted him to be a real cornucopia of colour. So that’s a little walk-through of the opening of the film, which takes you up to the end of “Jean Genie”. Where, again, we take a step back, and we say, “You don’t need to struggle – let it wash over you. You don’t have to understand everything.”

The interview material is fascinating, particularly the British TV clips with Mavis Nicholson and Russell Harty…

What I did find was that some of his best interviews were with women. However you want to interpret that. But my favourite interview that I ever found with Bowie was the outtakes for a movie called Inspiration, directed by Michael Apted. It was a movie from 1997; Apted did profiles of eight different artists, and the interviews are about their creative process. So that’s an hour and a half interview focused not on an album but on: ‘What is your creative process?’ Now, that doesn’t normally happen. David never put aside an hour and a half when he’s promoting a record to talk about not the record, you know? Because it was Michael Apted, he was speaking artist to artist, which was something he greatly enjoyed. So that interview really stands out and was probably the one I leaned the most upon. Mavis and Russell Harty sort of become characters, and then there’s a nice continuity in returning to them, I think. We use the Russell Harty clips from two different sequences, the ‘73 appearance, and then the ‘75 one, which is from Burbank. A nice little anecdote about that it was one of the great finds I discovered in the vault. David was living in LA at the time, so he went to the studio in Burbank. They were doing a live satellite feed, and while they were waiting to connect, someone was running tape on the set. David must have taken that tape home. So here’s this never-before-seen hour of Russell and David bantering back and forth before they went on air. That was one of my favourite discoveries, because it was so odd that it even existed – and that, of all places, I should find it in David’s vault.

Are you worried that not everyone will get the references?

As I mentioned earlier, the film is not about David Jones. And it’s not about David Bowie. It’s about ‘Bowie’ in quotations. The way I approached it was, everything is performance. I don’t mean that means it’s not authentic. If David’s onstage – he’s performing. If David’s in a movie – he’s performing. If David’s doing an interview – it’s a performance. If David’s being captured in a documentary like Cracked Actor – that’s a performance. If David’s being captured in a documentary like Ricochet – that’s a performance. So when you accept that it’s all in quotations, and it’s all performance, then The Man Who Fell To Earth is a documentary, and I’m going to extract and appropriate those images not as if David is shooting a film with Nic Roeg in Albuquerque but to visualise and articulate whatever sentiment that I’m trying to evoke. At the same time, one of the wonderful things about David is the way he transmitted information and introduced his audience to his own cultural heroes. When I first came to David, he turned me on to Burroughs, he turned me onto Bertholt Brecht and German Expressionism. This was at the age of 12 or 13. I had no other reference point. He’d mention something and you’d want to go read about it, like the Marquis de Sade or Oscar Wilde or whatever. So I liked the idea that, as part of the visual vocabulary of the film, I would use his sources of inspiration in a kind of indistinguishable manner to his own creations and constructions – it was all part of this same fabric.

How did that evolve?

You know, there was part of me that was like, ‘This film is really about the 20th century, on a certain level.’ I mean, the quote at the beginning is about Nietzsche, but it is equally could have been about Einstein, or Picasso or James Joyce, or Freud, or any of the other great minds that were deconstructing our belief system at the turn of the century. Y’know, David’s theme of chaos came about because he believed that, when we lost our idea of God, we also lost our sense on what to believe in. As society advanced, past the 16th century, where we went from an agrarian society to an industrialised society to a modern society in 20th century, how did our brains evolve to be able to process all this information? So what David posited was this: we live in a world of chaos – and he was creating the soundtrack for chaos.

What were you going to say about Bowie’s output after ‘95?

I think that period really starts at the end of The Glass Spider Tour [in 1987]. I’m not gonna lie, it was a little difficult for me when I got to The Glass Spider Tour. And, by the way, the further I went on, there would be more footage – for obvious reasons. So for the last tour he did, I had aeons of footage, but from ’73 there was very little. There was a lot of footage for Glass Spider, and it was wearing thin on me. Y’know, you gotta be pretty inspired to come in and work from 8am to midnight, six days a week. It was a slog. I’m very disciplined – I won’t fast forward through anything, because you don’t know if you’re gonna hear a great piece of audio or whatever. I watch every frame of everything. When I’d just about lost all hope, the next clip after the last piece of The Glass Spider Tour was a modern dance performance he did [with La La La Human Steps] in 1988. And it was really avant-garde. Now, he’s not the greatest dancer – he’s not the greatest painter either – but he puts all of himself into it. That’s why it’s so wonderful. And when I saw it – the first thing he did after Glass Spider – I was like, “Oh, shit, he’s back. He’s cleansing his palate.” Tin Machine really was a palate cleanser, the transition that was necessary, I think, to get to where he was going to get to with Iman.

Is there a reason there’s no Tin Machine in the film?

Y’know, I saw a couple of commenters online say, “Why didn’t he mention Tin Machine?” It’s always one of the things with these films that I get asked a lot. “How come you didn’t mention Iggy Pop?” I find this to be the weirdest thing for film critics. When they’re like, “He didn’t even mention Iggy Pop!” Well, if you knew that, what I that’s exactly why I didn’t put it in. Because I’m assuming you could fucking project a little something onto the screen! I mean, the movie at the end of the day was designed by trying to echo many of David’s ideas towards art, in terms of approaching art, a lot of the Oblique Strategies I would employ on a daily basis – like the idea that there are no mistakes, just happy accidents. I consider 80% of the edits in this film to be happy accidents that I intended to clean that up one day, and then later I was like, “I kind of like that it’s messy.”

The film does seem to confuse critics who think of rock’n’roll in terms of authenticity.

Yeah. I got into this really interesting conversation with one of the most iconic music producers of our time. He said, ‘What are you working on? And I said, ‘Bowie.’ He said, ‘You know, the two artists I’ve never been able to get into our Bowie and Springsteen.’ I said, why is that? He said, ‘Because they’re not authentic. He said, ‘Bruce has been playing his father his whole career. Bruce isn’t this blue-collar guy from New Jersey – that’s his dad. He puts on the blue jeans and a white shirt – it’s a performance. With David, everything is plastic and artificial.’ I said, ‘Dude, I don’t know about Springsteen, but I know about Bowie. He’s as authentic as it gets. He’s just employing techniques of distanciation, he’s employing a lot of Brechtian techniques. He’s about as pure as it gets.’