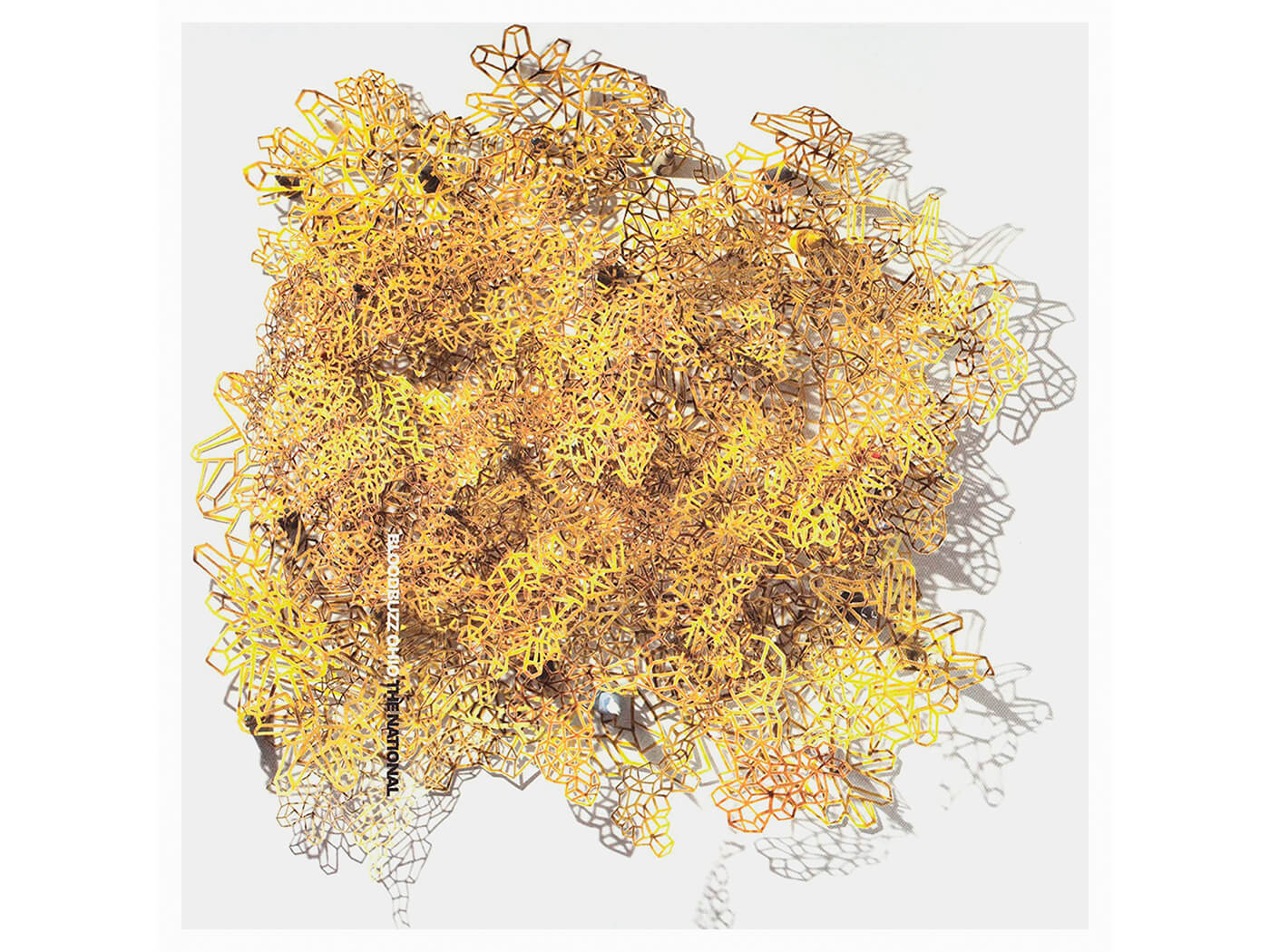

The National have announced details of a surprise new album, Laugh Track. To celebrate, here’s our piece on the making of their classic track “Bloodbuzz Ohio” from Uncut’s June 2020 issue.

Now read on…

In 2009, The National were burned out. They had toured solidly on the back of their Alligator (2005) and Boxer (2008) albums and found themselves in what guitarist Aaron Dessner calls “a dark place… It was exhaustion and everything that comes with being that fatigued,” he says. “Relationships were suffering. We almost broke up, actually.”

Instead, The National set up their own studio in Brooklyn’s Ditmas Park neighbourhood and made High Violet – an album of brooding magnificence that “healed the band”, reaching No 3 in the US charts and taking them into arenas and what Bryce Dessner describes as “another universe that wasn’t even in our vocabulary”.

“Everyone was more ambitious,” remembers vocalist Matt Berninger. “We could all feel that we were on the edge of something. There was the real possibility that if we didn’t fuck this up we’d never have to have real jobs again and we could play music for the rest of our lives.”

In 2008, they set out on tour with Modest Mouse – featuring Johnny Marr – and REM. “So suddenly we had a loose connection to two of our biggest influences, REM and The Smiths,” remembers Aaron Dessner. “Michael Stipe and all those guys pushing us felt like a real moment, like we’d been anointed or something. Realising that REM were good, hard-working people gave us confidence that if we worked at it we could be, you know, a great American band.”

Berninger suggests that tracks such as lead-off single, “Bloodbuzz Ohio” – a simmering anthem of nostalgia and displacement – were also inspired by the “great advice” Stipe gave them on that tour. “He said, ‘Don’t be afraid of writing pop songs.’ But the next night he said, ‘If you want to be a band that lasts, you have to write lots of hits or none at all.’ We wanted to write pop hits but had very different ideas about what that meant. ‘Bloodbuzz Ohio’ started as a sweet little folk song, which we transformed. But we knew that was a good one right away.”

Dave Simpson

AARON DESSNER: Back then, we put a tremendous amount of pressure on ourselves. None of us liked mainstream rock, so we weren’t trying to make something commercial. We wanted to build on what we’d already done with Boxer. Bigger sounds, with more orchestration.

MATT BERNINGER: I mostly remember my exhaustion. We had been on tour to promote Boxer for what seemed like years, because it was. Then my daughter was born. I wrote most of the songs in that half-conscious, under-slept mental state. Happy but a little delirious. Carin [Matt’s wife] says she remembers me writing on the edge of the bed a lot.

BRYCE DESSNER: My architect brother-in-law helped us make a studio in Aaron’s garage in Brooklyn. You could get two or three people in there. Someone might be standing in the garden playing, with a line leading into the amp inside the studio. Bryan [Devendorf] somehow got his drum kit in the garage. We were all living on the same block pretty much at that time, so we’d hang out, like a clubhouse, bit of drinking. Our community of artist friends was very involved. Richard Parry from Arcade Fire, orchestral players, brass or strings, a lot of different colours. I recorded a lot of the orchestration instrument by instrument, in the garage.

AARON: Because we weren’t running up studio bills, we had freedom to experiment. We were recording on Pro Tools. The energy was more important than high fidelity. The band usually writes the music first and even records quite a lot of it before Matt gets to the lyrics. Then a lot of it gets discarded. But with “Bloodbuzz” we had played versions of it live.

BRYCE: “Bloodbuzz” began as a folk song without a drum beat. It was originally written on guitars and ukulele – almost like an English ballad or something.

BERNINGER: I actually wrote to a mandolin sketch from [touring violinist] Padma Newsome. It was a sweet little folk song until Bryan brought in the beat, then Aaron really delivered on the arrangement.

AARON: We recorded endless versions of some songs on High Violet. There were about 100 versions of “Lemonworld”, perhaps almost as many of “Bloodbuzz”. When we went to [mixer] Peter Katis’s studio in Bridgeport we still hadn’t finished recording it, so carried on.

SCOTT DEVENDORF: “Bloodbuzz” became more of a rock song eventually. Matt was directing us: “I want it to sound like this!”

BERNINGER: Everyone was trying to break out of their habits and patterns – but we weren’t breaking in the same directions. I was pushing for uglier, fuzzier textures to get away from the sad-sack Americana label that had stuck to us from the beginning. I remember asking for guitars that sounded like “loose wool” or “warm tar”. Aaron was trying to interpret what that meant, while Bryce was bringing in these big, ambitious string arrangements. It was a struggle to get the ideas to work together.

AARON: Our song “Fake Empire” had this brass fanfare, so we asked Pad Newsome to write a similar part for “Bloodbuzz”, but right at the end of mixing Matt said, “We can’t have another fanfare song,” so we took it off. Peter Katis has a way of miking drums and making everything sound better, but he got really quite upset with us over that, actually. Because we’d recorded it and been performing it live like that. But Matt was right. There were a lot of aesthetic tugs of war.

BRYCE: It’s always intense between us!

AARON: There’s been a few times when it gets heated. Some people run hot, they have a quick temper. Others run colder. Matt and I have never had a fight or a loud screaming match, but we get upset with each other during recording. It’s the sign that you’re making something good, usually.

BERNINGER: We were actually trying not to fight as much as we used to. Making Boxer was a painful experience and nobody wanted to go through that again. I remember trying to focus on just battling the song, not each other, but it was a hard battle.

AARON : At one point I doubled the speed and played in a cross rhythm. Matt got mad. I still have the email. He thought I was ruining the thing. Then he got into it over time.

BERNINGER: We couldn’t ever get what we were all looking for. Everything felt like a cross-bred mutant. Eventually we gave up and embraced it. The whole album is like that. It’s a desperate record. It admits that openly in the song “England” with the line about being “desperate to entertain”. I usually have lots of lyrics and melodies piling up. I usually have an easier time writing to simple guitar or piano ideas, but this time they were sending me complex arrangements with different guitar parts and key changes.

AARON: The first time we heard the lyrics was when Matt sang them. We all have our own ideas about what “Bloodbuzz Ohio” means. To me it was a lament, an existential nostalgic love song about where we’re from, about family and the way America is so frayed and divided. So you can be family in blood but estranged because of social values. Obama had just gotten in, but we were coming out of the Bush years and the financial crisis had meant people had worked their whole life and watched their savings just disappear. Hence “I still owe money to the money to the money I owe.”

DEVENDORF: There’s a homesickness to the song. We’re a band from Ohio that formed in New York. So we were channelling a feeling of being far away from a place you knew in another life.

BRYCE: “I was carried from Ohio on a swarm of bees.” I grew up in Ohio so I have a fondness for it, but it’s a place that’s quite disturbed. Everything that’s wrong in America, you can find there. Ohio is a beautiful place with amazing people, but also hard problems, social, economic issues and racism. It’s a swing state, red and blue. We grew up in that environment.

BERNINGER: It’s about being stuck between an old version of yourself and the one you’re becoming. I was trying to shed my skin. That’s what the first line about lifting up my shirt means to me. I definitely didn’t feel like the same person I used to be. I didn’t feel like an Ohioan any more and I definitely was not a New Yorker. I was married with a baby, living in Brooklyn, which was still a foreign land to me, and on the verge of becoming a rock star if I didn’t blow it. It was winter, and I remember pacing around ice puddles in Peter Katis’s yard trying to finish the words.

DEVENDORF: By now there was a deadline – partly from us and partly the label – and we were rushing towards it. It wasn’t all dour, but I remember Matt getting really sick and then his grandmother died.

BERNINGER: I’d just quit smoking after 15 years, and when you quit cold turkey like that you’re kind of coughing shit up for a while. Then I caught a really bad cold on top of that. I could barely sing, so we postponed everything for a couple of weeks. Then when I flew to Cincinnati for my grandmother’s funeral, my eardrum ruptured when I landed from the sinus pressure. Blood was coming out of my ear when my parents picked me up. I couldn’t even hear the eulogy. When I got back to the studio I had very little hearing in my right ear. Apparently, Aaron would pan stuff that I didn’t like to my deaf ear so I wouldn’t notice it.

BRYCE: The doctor put Matt on horse steroids as we were finishing the mixing.

AARON: Matt was discovering these different aspects to his voice. On Alligator he was screaming. On Boxer he found an almost whispered murmur. By High Violet he found something else, kinda iconic. He found the sweet spot in his voice. He couldn’t get healthy, and you can hear that on the record, but it’s a great performance.

BERNINGER: It was tough to get through the vocals, but not just because of the cold. I used to just chant or mumble, but I wanted bolder, more musical melodies and it took me a while to get there. Every time I would try a more ambitious melody, Bryan would start singing Will Ferrell’s impersonation of Robert Goulet doing “Red Ships Of Spain”. When I listen to High Violet now, I definitely hear that.

BRYCE: Bryan’s drums are almost like what a guitar riff would do, this really iconic, recognisable riff, but on drums. Bryan’s really methodical and writes his parts out so they have interesting patterns. They’re not intuitive. He’s very influenced by Stephen Morris from New Order and that feel. With “Bloodbuzz”, the piano riff inspired the drum beat.

AARON: We recorded Bryan’s drums so many times. It wasn’t about the playing, it was the sound. He played the drums to “Bloodbuzz…” yet again on the very last day. We were in perfectionist mode.

DEVENDORF: Some songs don’t reveal themselves until the end. When there was lyrics and drums it became, “OK, this is what the song is now.”

DESSNER: The guitar hooks were added on the last day, I think. The fuzzy guitar solo was also done very late. It was super hard to find those details.

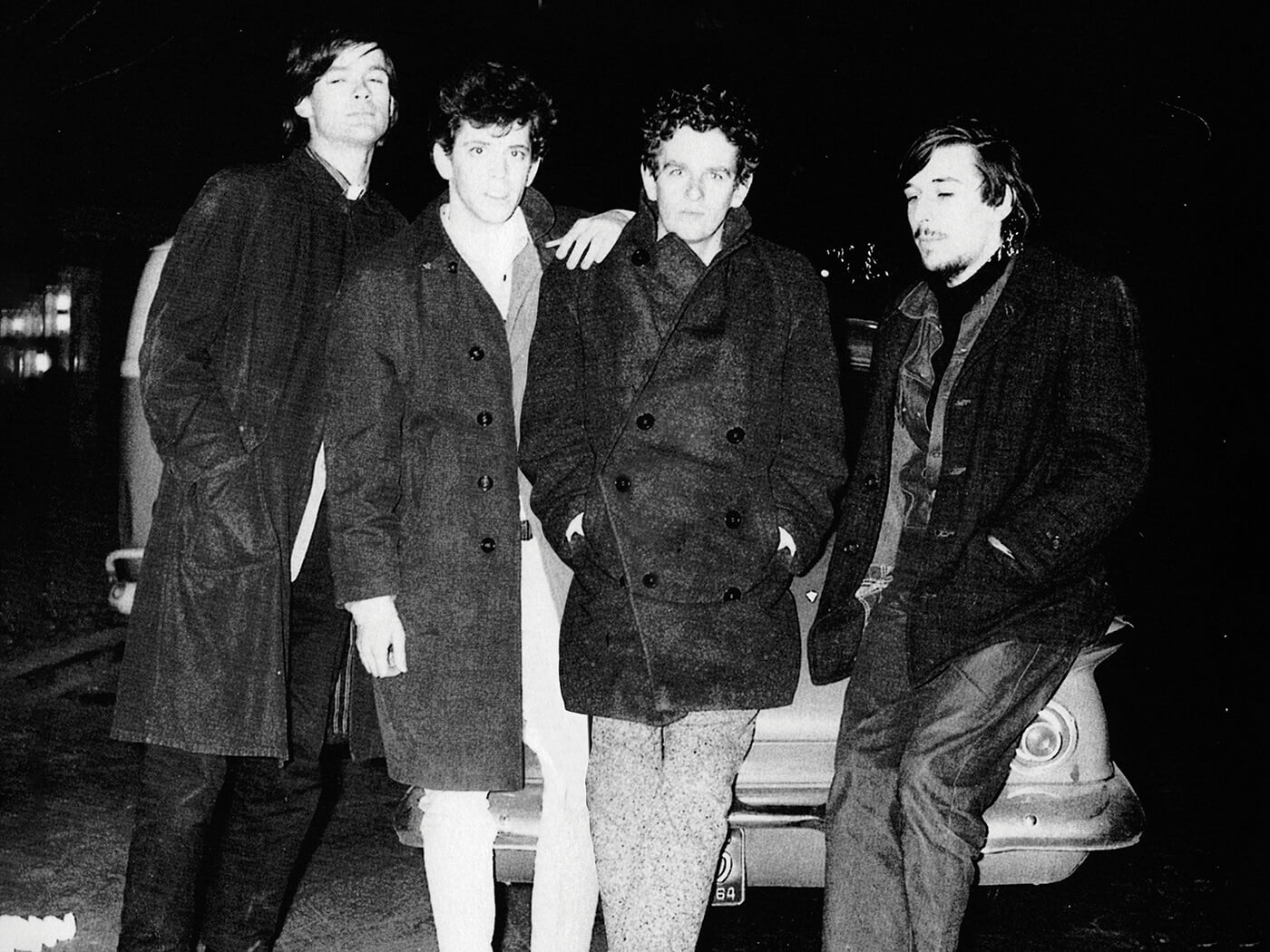

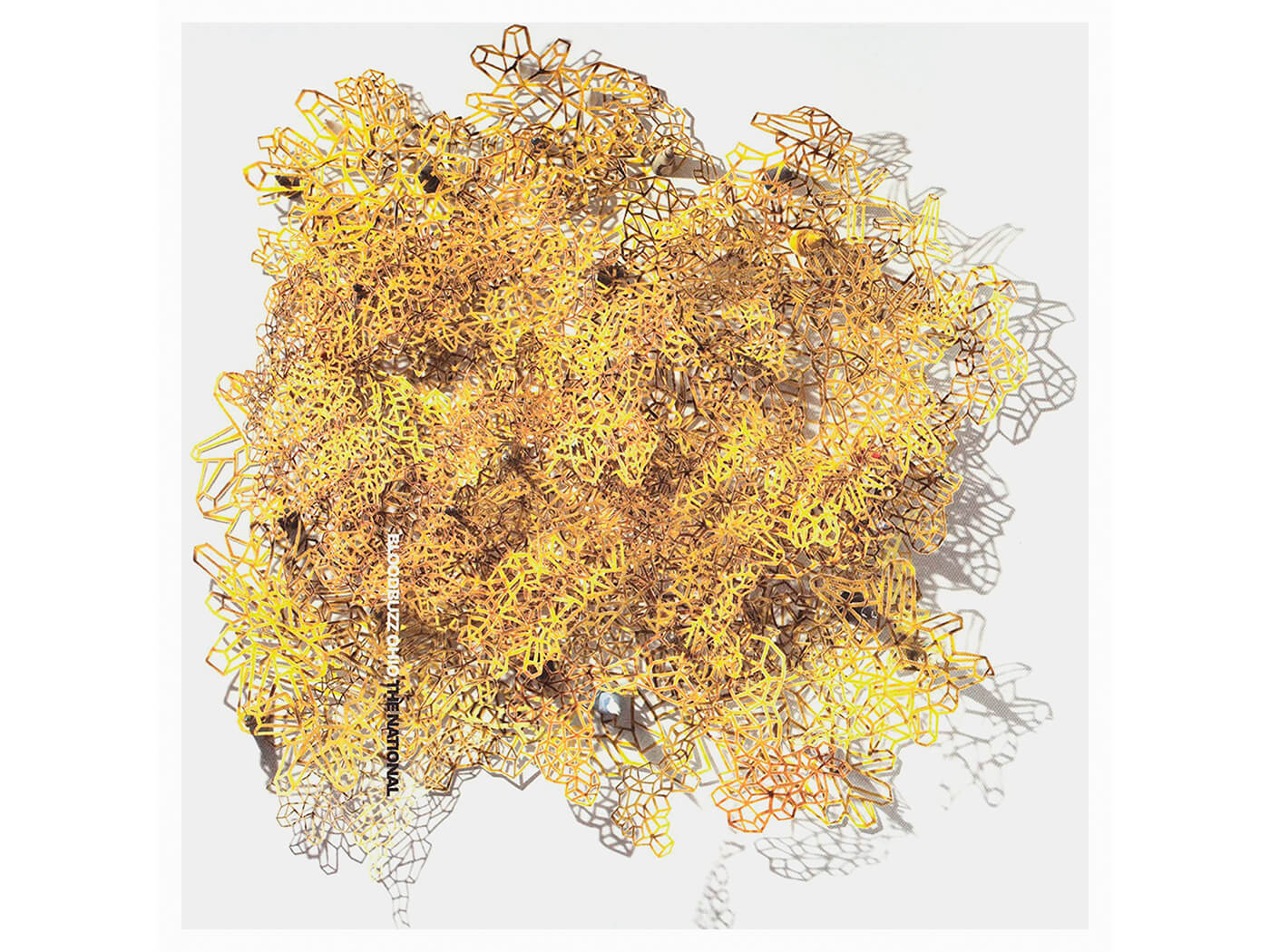

DEVENDORF: The pictures on the [High Violet] sleeve are testament to how tired we were by the end. We all look worried or grumpy. There’s a lot of unseen tension on that record. Operating as a democracy added to it, but the dynamic got us to a place where we’re all satisfied.

AARON: We were obsessed. We kept circling the vortex as we wanted to make a timeless classic.

The National play All Points East on Friday, August 26. For more info, click here.

They play Connect Festival on Sunday, August 28. For more info, click here.