Originally published in Uncut’s July 2022 issue

“I think it was shown on MTV once, maybe twice,” says bassist James McNew, remembering “Sugarcube”’s video. “As far as I know, that’s it. That’s all.”

In the 25 years since, however, the promo has racked up millions of views on YouTube, no doubt helped by the presence of its stars David Cross and Bob Odenkirk, the latter now better known as lawyer Saul Goodman in Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul. He has, it turns out, been a Yo La Tengo fan since the early ’90s.

“We were all fans of Bob’s from The Larry Sanders Show,” explains Ira Kaplan. “Then Georgia and I were on vacation out in LA and we saw that Bob was doing stand-up at a bookstore, so we went out to see the show. Afterwards he was just browsing the record section, and it was kind of out-of-character for us to do this, but we introduced ourselves. It turned out he knew our band.”

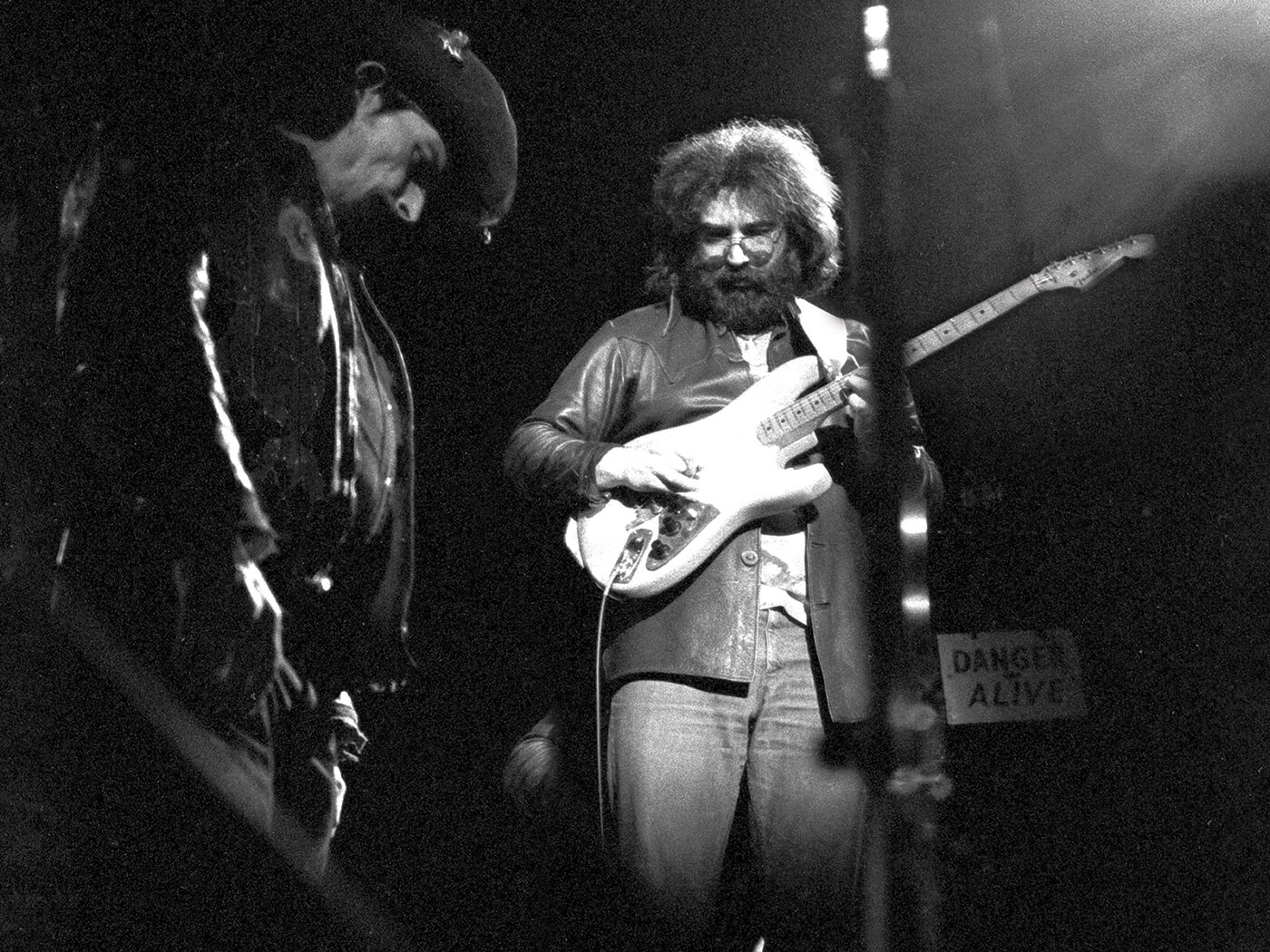

There’s more to “Sugarcube” than its video, of course. Since the mid-’80s, the Hoboken-based group had been charting a unique path, mastering the acoustic hush of 1990’s Fakebook as adeptly as they did the brutal fuzz workouts of ’92’s May I Sing With Me. On their eclectic eighth album, 1997’s I Can Hear The Heart Beating As One – now celebrating its 25th anniversary with a digital and vinyl reissue – they perfected this sonic tightrope walk. “Sugarcube”, a highlight of its 16 tracks, is a propulsive, droning delight, Hubley’s drumming and McNew’s unusual organ bass driving Kaplan’s freeform guitar wrangling and their surprisingly gentle harmonies.

“It feels really natural to play “Sugarcube” or to play [quiet instrumental] “Green Arrow”,” says McNew. “Loud music is us and quiet music is us, atmospheric music is us and straight-ahead music is us. We were more comfortable with that idea than other people were, it seems.”

Recording took place in Nashville’s House Of David, a studio converted for Elvis Presley, with the sessions – somewhat typically for Yo La Tengo – efficient and exploratory at the same time. “We’d recorded before at Alex The Great in Nashville,” recalls Hubley, “which is a much more bohemian studio, with a lot of character. But House Of David was on a real street, with a lot of music industry stuff on that road, you know, publishing companies and other recording studios.”

“There were these big magnolia trees in the front yard,” says producer Roger Moutenot, summing up their quest for experimental spontaneity. “One time we went out there and the crickets were just crazy, so I ran in, set up two microphones on the front porch, and we recorded these crickets for “Green Arrow”. At one moment, this one cricket just stepped forward and almost took a solo. We were all just cracking up! It was beautiful. But that was the fun thing about Yo La Tengo – there was nothing too off-the-wall, no boundaries. This was a very free and expressive record to make.”

GEORGIA HUBLEY (drums, vocals): I remember we were pretty excited about the things we were coming up with for I Can Hear The Heart Beating As One. We had a pretty crappy rehearsal room in Hoboken, but it was great, we were able to have all our stuff set up, and we’d just keep trying different things.

IRA KAPLAN (guitar, vocals): When we got to the point where we didn’t have to do anything else but be a band, it was great because we could practise during the day. When we had night-time practices, it would be kind of cacophonous with other bands playing simultaneously. But by the time of I Can Hear The Heart Beating As One, we were able to work pretty much every weekday afternoon.

JAMES McNEW (organ, percussion): The space has since been demolished and turned into luxury condominiums, as has most of Hoboken, actually. But yeah, we would just play with no real destination in mind, and come up with jams and ideas that were fun to play and that seemed interesting.

KAPLAN: Our rehearsal room was located next door to a woodworking place, and one day as we were walking to practice we saw Teller from Penn & Teller on the street. It turned out they were having some stuff fabricated for them at the shop. At some point we came out of rehearsal and Teller was there, and then we saw blood flying out of his hand. Apparently he was testing some blood-spurting device.

HUBLEY: “Autumn Sweater”, for instance, was started on guitar, and then it just moved over to organ, but that was pretty indicative of a lot of the writing. “Sugarcube” doesn’t have bass guitar, it’s just James playing bass on our Acetone, our beloved, trashy Italian organ, which is very bassy-sounding.

McNEW: I don’t even know where we got the Acetone. It was just in our practice space. We noticed that no-one was ever using it – there was dust on it. So we decided to pay some attention to it, and it turned out to be so great that we would all take turns playing it on different songs. I liked the idea of organ acting as bass – you know, it had a lot of good precedents in Suicide or Snapper, things like that. It was a sound that I really like.

KAPLAN: Electr-O-Pura had been the first record that we’d made exclusively with Roger. We went to Nashville to make that.

ROGER MOUTENOT (producer): We made a deal where they’d come down here to record, and then I would go up to New York to mix. That was the arrangement.

KAPLAN: Going back to Nashville for I Can Hear The Heart…, I think we all felt pretty comfortable, and excited about the songs we had. There were definitely songs where we really didn’t know how they went, we were kind of allowing the process of recording to give us the chance to finish and change songs as freely as we wanted.

MOUTENOT: House Of David was a weird choice for a studio, but I had worked there, and I really, really liked the console. So I thought, ‘Oh, this will be good for this project.’ It had this unique vibe: Elvis was going to work there, and they built this whole entranceway off the garage, so he wouldn’t have to walk outside the building. There was actually a trapdoor that went into the garage, and that was for Elvis.

HUBLEY: I keep trying to visualise the place – I can see the room where we set up, and then there was a little downstairs area where we had a TV and we would watch reruns or whatever, when there was nothing for us to do, if they were working on machines that needed to be repaired or anything like that.

McNEW: They had cable TV, which was a great novelty back then. It was a nice place, a terrific [live] room, and the control room was really nice to use.

MOUTENOT: Most tracks were recorded live, as live as we could get. Sometimes we did vocals too, but I think for “Sugarcube” we just cut the basic tracks. For the most part, the Yo La Tengo stuff I worked on was always live to start with, just to get that band thing. There were a couple of songs on I Can Hear The Heart… that were built up, though, like “Moby Octopad”, which started with drums and then bass, and things like Ira’s piano were overdubbed later.

KAPLAN: I remember us coming up with the little ending for “Sugarcube”. It’s ancient times, so it was recorded on tape, and when you finished you’d rewind the tape machine. If you didn’t turn down the faders you’d hear the sound of the tape going backwards, played really fast. It sounded great, so we recorded that and stuck it on the end.

HUBLEY: The intro with the drum fill, I really cannot remember how that came about: it has to be some sort of weird accident that we decided to keep. I wish I remembered, because it’s so weird and random. I do remember thinking, ‘That’s terrible sounding’ but everybody else was like, “No, that’s great!” It kind of works.

MOUTENOT: That was a special fill! It may have been that Georgia did the fill and I was like, “Oh my God, that’s so great, let’s use that take.” But you know, I did cut between some takes once in a while – I did a bit of editing on that record as it was recorded on tape. I can’t say, but it might have been that.

McNEW: I remember Roger deciding that he needed to do some cutting on tape, and it was as though he was about to defuse a bomb. He ordered everyone out of the control room, so it was just him and whoever the assistant from the studio was. He told us all to just go get lunch, just get out of there while he did this extremely life-or-death manoeuvre on the tape. It was a mystery to me! I just knew that he was doing something very important, and I wanted to give him his space. Though I think that drum fill was actually a part of the arrangement. I don’t recall how it began, where it originated from, but I think it was always part of the beginning of the song, strangely enough.

MOUTENOT: That’s what I love about this particular record, I Can Hear The Heart…, it’s up, it’s down, it’s rocking, it’s soft, it’s got a lot of different textures and feelings. Like, “Damage” is one of my favourites, it just puts me in a dream world every time. When you make a record that way, when you open the can of worms like that and say ‘anything goes’, you could go down the rabbit hole and really get screwed up. But for some reason, with these guys, it all worked because we always would go somewhere but pull it back in to be what the band wanted. It was super fun.

KAPLAN: Apart from being in it, we had very little to do with the video after coming up with the concept – the plot of doing this lousy video and irritating the record company, and then them sending us to rock school; and then we do the exact same video as rock school graduates, the same as they one they hated, but this time they love it. That was what we presented to our pal Phil Morrison, who had directed the “Tom Courtenay” video and a couple of others that we did. Then Phil took that concept and him and his writing partner Joe Ventura came up with the script for the video.

HUBLEY: We knew the storyline, such as it was, but a lot of it’s improvised – certainly, Bob and David do a lot of improvising. We flew out to California just to do the video. I think it was maybe a two-day shoot in a variety of locations, but mostly at a high school or college in Santa Monica. It was shot at a weekend in the summer, so it was fairly empty and easy to film there.

McNEW: It just seemed like a weird dream that it was actually happening – it still seems like a weird dream that it did happen. I mean, I remember just how deeply committed to the idea Bob and David were. They really delivered and gave so much more than you would ever even have possibly imagined that they would give to such a such a ridiculous idea. That’s just kind of inspiring, and it shows how gifted both of those guys are.

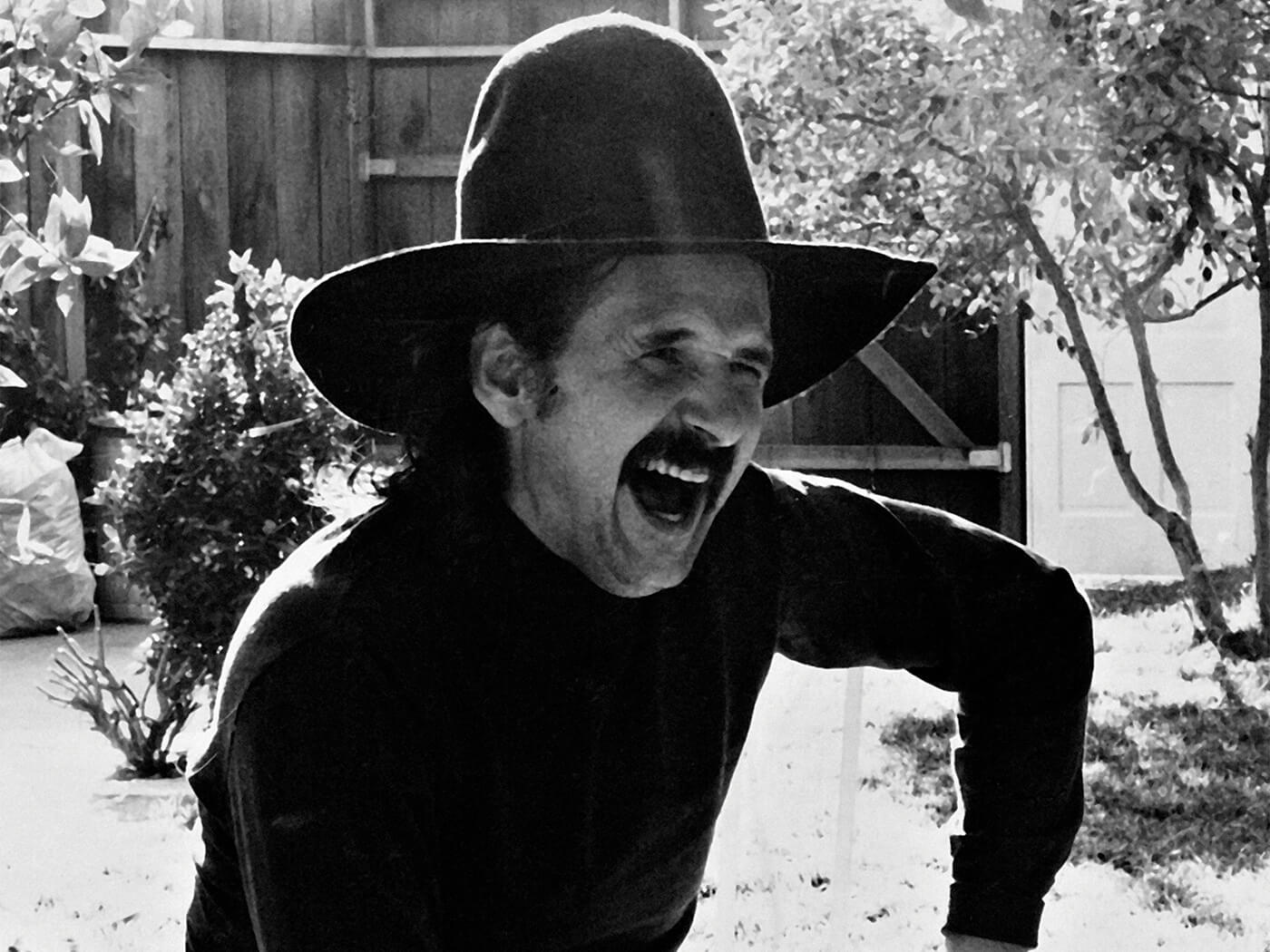

KAPLAN: It was really fun. I wish the shoot had been longer. The only part I remember being gruelling at all was filming the scene where we’re getting yelled at by John Ennis, with Bob and David playing the record company flunkies. We were filming in an actual office, and because there was dialogue there was no way you could have AC on. Maybe because it was the weekend the air conditioning was off anyway? But it was really hot in there. That is the closest I can come to a complaint, because it was hilarious. All these takes kept being ruined, because either John was laughing or we were laughing.

McNEW: Keeping a straight face was a pretty sizable challenge. That scene in the boardroom where John Ennis is screaming at us, it was impossible to try to act our way through that. It’s very strange and amazing to see Bob [so famous] now, on television, in theatres. Of course, I’m not surprised, because I felt that he should have been there all along. I think that he’s a genius, as is David. But it is strange when universes collide all of a sudden. I know that I have esoteric tastes, and when they cross over into the mainstream, it’s surreal to think that, ‘Oh, everybody likes Bob. That’s great. That’s fantastic.’

I Can Hear The Heart Beating As One is being reissued both digitally (out now) and on coloured vinyl (out now in the US & Canada, and August 12 elsewhere) for its 25th anniversary, via Matador

__________________

FACTFILE

Written by: Ira Kaplan, Georgia Hubley, James McNew

Personnel: Ira Kaplan (guitar, vocals), Georgia Hubley (drums, vocals), James McNew (organ, percussion)

Produced by: Roger Moutenot

Recorded at: House Of David, Nashville, TN

Released: April 22, 1997 [album], August 4, 1997 [single]

Chart peak: UK -; US –

__________________

TIMELINE

February 28, 1992

Yo La Tengo release May I Sing With Me, their fifth album but first with bassist James McNew

May 2, 1995

Electr-O-Pura marks the band’s first time recording in Nashville entirely with producer Roger Moutenot

April 22, 1997

I Can Hear The Heart Beating As One is released – though it has stiff competition, it remains perhaps Yo La Tengo’s finest LP

August 4, 1997

“Sugarcube” is released as a single, backed on 7” by B-side “Busy With My Thoughts”, and on CD by “The Summer” and a 14-minute take on Eddie Cantor’s Looney Toons theme, “Merrily We Roll Along”