One phrase which kept returning to mind while working on this new magazine was “Quiet is the new loud”. Back in 2001 it was the name of an excellent album by the lovely Norwegian group Kings Of Convenience (included, of course, in the collection of fine music we’ve democratically assembled for you here). But it was also a kind of ethos.

One phrase which kept returning to mind while working on this new magazine was “Quiet is the new loud”. Back in 2001 it was the name of an excellent album by the lovely Norwegian group Kings Of Convenience (included, of course, in the collection of fine music we’ve democratically assembled for you here). But it was also a kind of ethos.

As Fleet Fox Robin Pecknold explains in his excellent introductory interview to the magazine, from his point of view the 2000s were a simpler time. So dominant was the aggressive and neurotic nu metal which was the big commercial force in rock music as the 1990s turned into the next century that the choice was clear cut: it became a key mission to find an escape in other – better – sounds.

For Robin, this meant drinking in the weekly dramas of the Libertines, and following the explosion of the Strokes and White Stripes as they were chronicled in the British music press. As his own musical mission developed it became obvious that retreating into quieter, folkier sounds, more like the Joni Mitchell records he grew up listening to in his parents’ record collection could hold the answer.

He wasn’t the only one. After a series of personal and romantic disappointments, Justin Vernon took himself off to a remote Wisconsin cabin to develop one of the most influential sounds of the next ten years. A minimal, tender and eerie album, there’s a feeling in Bon Iver’s For Emma, Forever Ago album of an attempt to strip away inessential elements and reconnect with the essence of music making.

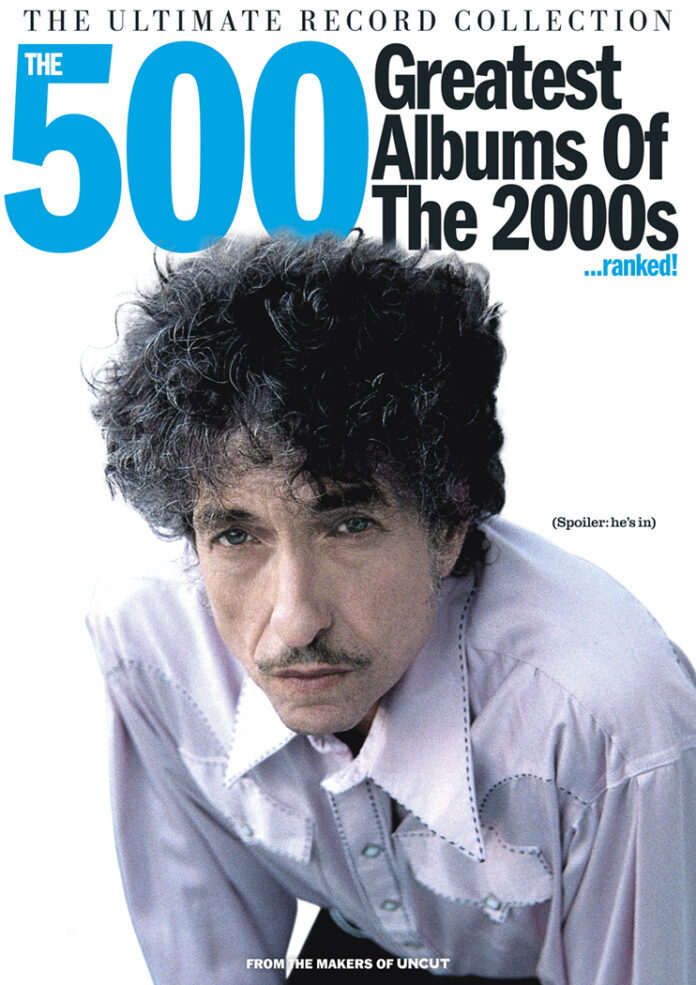

You’ll find something like it in the bare bones of “Love And Theft”, part of our cover star Bob Dylan’s vital career reset in the period. This tendency didn’t mean you needed to be a luddite to look for it, though: you’ll also find it in the electronics of Radiohead albums like Kid A and In Rainbows or the icy synths of Portishead‘s Third. The band’s song “Machine Gun”, Uncut wrote at the time was “a folk song from a Britain broken so much more intimately and profoundly than anyone had guessed.”

Back on our call, Robin Pecknold is characteristically humble about his role in defining the aesthetic of the latter part of the decade. “All it took was playing a few tasteful references,” he tells Mark Beaumont. “There wasn’t any streaming, so it was a little bit easier to have obscure influences because there wasn’t that access to everything. It seemed easier compared to now, because now what’s happening in the mainstream isn’t quite as weird and bad. It was a more innocent time.”

Enjoy the (relative) peace and quiet, and the magazine. You can get yours in shops tomorrow and here now.