“There is no band more mythical than Faust,” wrote Julian Cope in Krautrocksampler, his grand survey of German kosmische music. If Faust are mythic, maybe it’s because the group – formed in 1970 in the counterculture ferment of Hamburg, West Germany – remain resistant to category. Their im...

“There is no band more mythical than Faust,” wrote Julian Cope in Krautrocksampler, his grand survey of German kosmische music. If Faust are mythic, maybe it’s because the group – formed in 1970 in the counterculture ferment of Hamburg, West Germany – remain resistant to category. Their immediate peers in ’70s German progressive music often felt like the embodiment of certain concepts. Kraftwerk were about the bold march of technology; Can, improvisation as liberation; Tangerine Dream, the sweeping expanse of space. Perhaps what makes Faust mythical is that they are so difficult to pin down.

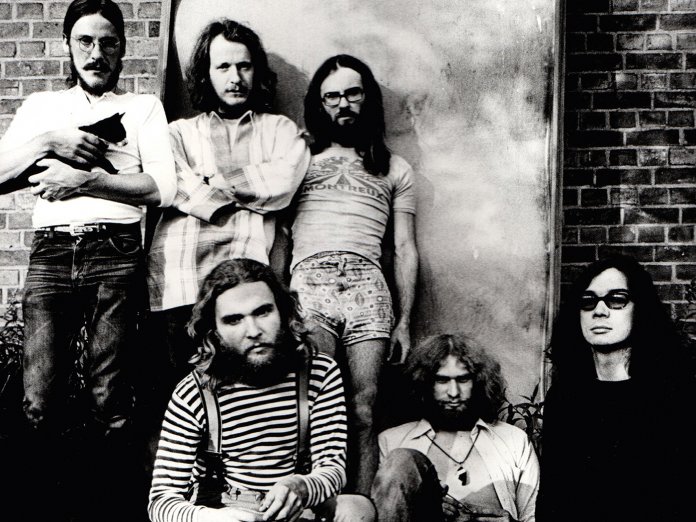

In part this was a question of personnel. Faust had its leaders – drummer Werner “Zappi” Diermaier, bassist Jean-Hervé Péron and the underground journalist turned impresario-cum-producer Uwe Nettelbeck – but the group operated as an anarchic collective in which individual contributions were subsumed within a unified whole. In part it was their sound, which encompassed bucolic folk, avant-garde sound collage, synthesiser experimentation and fuzz-wreathed freakouts, that beat a path to the distant horizon. All this, and Faust were funny – humorous in that distinctly German way that translates awkwardly into English.

If Faust remain a little obscure next to their peers, maybe it’s because some half a century on, their music is yet to be fully understood. Their records have never been out of print, but there has been no proper retrospective – at least until now. The 1971–1974 box collects their four studio albums, Faust, Faust So Far, The Faust Tapes and Faust IV. It also assembles a “lost” album, Punkt!,plus two discs entitled Momentaufnahme I and II (in English, “snapshot”) collecting music recorded at their studio, a converted schoolhouse in rural Wümme. Completing the package is a pair of singles, including the pre-Faust demo recording Lieber Herr Deutschland. A mix of hard rock, protest sounds and political sloganeering very in tune with the post-1968 counterculture, it somehow scored the young Faust a major record contract with Polydor, a rather conservative label looking for an emissary of the new German sound.

Come their debut album, Faust had insurrection on their mind; but 1971’s Faust is a sonic revolution, not a political one – a deliberate rupture with rock history. It begins with brief samples of The Rolling Stones’ Satisfaction and The Beatles’ All You Need Is Love, mischievously tossed in, and from thereon in, anarchy reigns. There are squalling horns, field recordings, seasick jazz rhythms, bierkeller singalongs; its surreality, and its bloody-mindedness, is thrilling. 1972’s Faust So Far is equally strange, but rather more structured and accessible, throwing in pop moments – see It’s A Rainy Day (Sunshine Girl), a mix of ’60s beat group charm and primitive Velvet Underground thud – and a playful virtuosity best spied on spry jazz-rocker I’ve Got My Car And My TV.

Cast off by Polydor, Faust signed with Virgin Records on the condition their new double album would retail for 49p, the price of a seven-inch single. Assembled from hundreds of hours of recordings captured at Wümme, The Faust Tapes was a sprawling sound collage – 26 tracks – that seemed designed to bewilder casual listeners and delight the seasoned. The two Momentaufnahme discs feel like a logical extension of The Faust Tapes, highlights including woozy drum jam Vorsatz and the self-explanatory Weird Sounds Sound Bizarre.

Perhaps it’s easiest to comprehend Faust’s legacy through a listen to Faust IV. The group’s most accessible album, here you can hear seeds laid for everyone from The Beta Band (the sprawling, bucolic Jennifer) to Thee Oh Sees (chunky psych jammer Giggy Smile). The surging 11-minute opener Krautrock is somehow monumental enough to deserve its definitive title, even if Faust doubtless named it in arch response to the music press’s faintly insulting genre name.

The most exciting addition on 1971–1974 is Punkt! Recorded in Giorgio Moroder’s Musicland studio in 1974 but never released, it finds Faust paring back their jazzy eccentricities, instead pointing forward to the music the reformed group would make from the ’90s onwards. Morning sets the tone, an industrial-strength rock freakout powered by Zappi’s pneumatic drumming, while Knochentanz adds a faintly Arabic flavour through droning horns and dervish percussion. But there are pretty moments too – the piano-led Schön Rund; and especially Fernlicht, a synth instrumental with a dreamy, elegiac feel. The session for Punkt! ended inhigh farce, a studio smash-and-grab that saw the masters spirited out in the back of a van and Hans-Joachim Irmler and RudolfSosna tossed in prison. In a way, it was a surprise Faust got away with it for so long: four years of sonic invention that, even now, sounds like a radical act.