In 2019, an extensive reissue campaign of David Sylvian’s solo albums reminded us how far this reluctant star had retreated from the limelight. Who could blame him? Japan found success too late, after they had already decided to split, when personal conflicts became unendurable. It’s a situation laid out on “Ghosts”, the exquisitely cold and distant highlight of their fifth and final album, 1981’s Tin Drum. “The ghosts of my life blow wilder than before”, mourned Sylvian, lost somewhere deep inside his own anxieties. But let us remember happier times, where the band’s vision finally coalesced.

Japan had formed in south London during the early ’70s – glam touchstones included the New York Dolls (Sylvian’s real name is Batt), Roxy and Bowie. The early part of their career is full of false starts, including a dismal tour supporting Blue Öyster Cult and two largely ignored albums, Adolescent Sex and Obscure Alternatives (both 1978). But as the decade ended, their lot improved. “The Tenant”, the slow-moving instrumental that closed Obscure Alternatives, was the first of Sylvian’s Satie-inspired piano pieces. Meanwhile, “Life In Tokyo”, a standalone single with Giorgio Moroder, marked their transition away from glam revivalists.

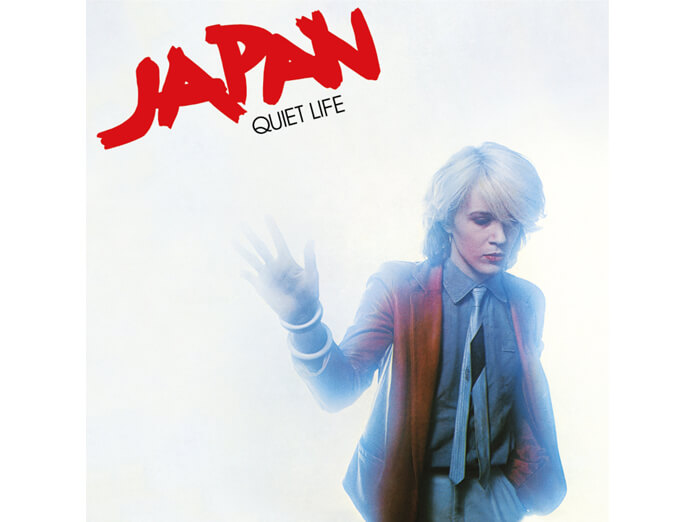

By the time they recorded Quiet Life, Japan had refined a new creative direction – artfully pitched somewhere between the opiated chic of late-period Roxy, the haunting abstractions of Bowie’s Low and The Velvet Underground’s noir glamour.

But despite the swish flourishes of their new sound – sympathetically recorded by Roxy producer John Punter – the songs on Quiet Life seemed to foreshadow Sylvian’s own knotty relationship with fame. “Boys, now the times are changing/The going could get rough”, he sings on the title track. Elsewhere, on “Fall In Love With Me”, Sylvian is stirred from his woozy, Ferry-esque croon and all but howls, “Shy away from standard life/Each bitter moment lingers on”. On “Despair”, meanwhile, he sings of “the artists of tomorrow” who live “in pleasant despair”. It’s an outlook you suspect Sylvian found faintly romantic.

Of course, there is more to Quiet Life than simply David Sylvian’s inward meditations. There is his younger brother Steve Jansen on drums, multi-instrumentalist Mick Karn – with whom Sylvian had a competitive, ultimately damaging relationship – keyboard player Richard Barbieri and guitarist Rob Dean. The title track brilliantly summarises their strengths – Karn’s sinuous fretless bass, Jansen’s metronomic drumming, Dean’s chiming chords and E-bow playing lying beneath Barbieri’s keyboard rises. It impressed Duran Duran so much, they based their entire career around it.

Elsewhere, Quiet Life finds Japan gamely exploring their newfound capabilities. Dean’s Fripp-like runs on “Fall In Love With Me” butt against Karn’s squalling saxophone; “Halloween” pushes the band further towards the cinematic avant pop of Gentlemen Take Polaroids. A polite version of “All Tomorrow’s Parties”, built around Dean’s cyclical guitar lines, is carried by Sylvian’s wistful delivery.

Arguably, Sylvian was more comfortable in the quieter moments. His woozy croon stretches out in the space between the instruments – on “Despair”, say, where he’s accompanied by Barbieri’s keyboard and Karn’s saxophone. He gradually recedes from the song as Barbieri’s chilly atmospherics build into an extended coda modelled on Bowie’s “Warszawa”. Karn’s expressive fretless basslines and Barbieri’s textured synth beds provide Quiet Life with its musical character – as on “In Vogue” or “Alien”, which sweep forward with imperious grace. Starting out as another enigmatic piano piece, the album’s seven-minute closer, “The Other Side Of Life”, develops into a thrilling, widescreen finale, with Sylvian’s baritone rising to meet Barbieri’s swelling synths and sumptuous string arrangements.

Emboldened, Japan maximalised their Quiet Life achievements on Gentlemen Take Polaroids and, finally, the fearlessly ambitious Tin Drum. These three records mark a distinct phase in Sylvian’s career, setting out a path for creative and commercial success that he ultimately rejected in favour of more oblique strategies. His former bandmates similarly found creative outlets outside the mainstream. Quiet Life, though, enabled Japan to get from B to C, and from D to E, and from there to wherever they went next.

Extras: 8/10. A second disc collects 7” and 12” remixes as well as standalone tracks like “Life In Tokyo” and “European Son”. A third disc, recorded live at Japan’s Budokan, captures the band at full tilt.

Q&A

STEVE JANSEN

Quiet Life feels like a band finally working out who they were. What do you think accounted for that?

The first album, and to a large extent the second, was the band’s opportunity to record material it had been touring for a number of years. We took a much more measured approach when recording Quiet Life. We were far more conscious of musicianship and interplay rather than simply a great song. Saying that, the songwriting had started to develop a more sophisticated ‘poetic’ or ‘romantic’ flavour rather than the previous angry, subversive content, and this in turn would have determined a more subtle, expressive approach to the instrumentation.

How important was John Punter’s involvement?

With his knowledge and experience in the studio we felt we had everything in place to really make something we were going to be proud of. We were extremely keen to push ourselves within the creative process of recording.

What was the dynamic like in the studio?

We couldn’t have been happier or more enthusiastic. Each person was focused on their role within the band but also critiqued the others, which was taken on board with good humour and a willingness to grow from the experience.

Looking back, how do you view Quiet Life now?

I think it was our first real statement as a band. I think the songwriting soared ahead in leaps and bounds and the musicianship and attention to detail was the beginning of the road to Tin Drum.

Book Of Romance And Dust by Exit North is out now

INTERVIEW: MICHAEL BONNER