In 2014, Canadian songwriter Kathleen Edwards surprised everyone when she announced she was stepping back from music, moving back to her hometown and opening a coffee shop called Quitters. The name was tongue-in-cheek, in line with the self-deprecating humour found in Edwards’ music whenever thing...

In 2014, Canadian songwriter Kathleen Edwards surprised everyone when she announced she was stepping back from music, moving back to her hometown and opening a coffee shop called Quitters. The name was tongue-in-cheek, in line with the self-deprecating humour found in Edwards’ music whenever things were getting too serious. But as the years passed, and Edwards shared more about the depression that soured the release of her 2012 Polaris Prize-shortlisted masterpiece Voyageur, new music seemed increasingly unlikely.

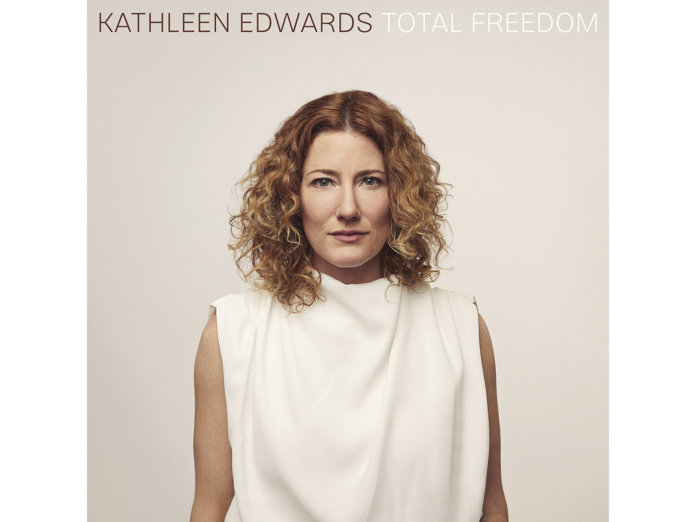

It turns out that a break was what Edwards needed to fall back in love with songwriting. An invitation to co-write in Nashville with Maren Morris and Ian Fitchuk, fresh from his work on Kacey Musgraves’ Golden Hour, turned into writing for herself again – and those songs became Total Freedom, her first album in eight years. Recorded partly in Nashville with Fitchuk and partly at home in Ontario with longtime collaborator Jim Bryson, its 10 tracks sing with warmth, love, gratitude and lessons learned.

“Glenfern”, named after the street where Edwards first lived with ex-husband Colin Cripps, is a breezy, nostalgic album opener and one that circles back to Voyageur, an album often misinterpreted as being about the breakdown of the couple’s marriage and Edwards’ short-lived relationship with co-producer Justin Vernon. The song is packed with loving details, both domestic and professional: touring the world and playing with their heroes, Cripps caught on Google Street View “in your slippers on the front porch with the Siamese cat”. “It’s not up there any more, but I will always be thankful for it,” Edwards sings warmly, in the same tone she applies to reminiscing about her later successes.

Edwards’ photographic memory for the little details, and ability to translate them into the perfect lyric, is one of the reasons that Failer, her 2003 debut, still resonates two decades later. Those details can charm: sleeping dogs at sunrise on “Birds On A Feeder”, the friendship at the heart of “Simple Math” that retains its magic “now we are our mothers’ ages”. But they can also devastate, whether it’s a painted rock under a catalpa tree marking the final resting place of Edwards’ beloved golden retriever, or the throwaway lines – pulled threads in sweaters, unpaid birthday dinner bills – that taken together paint a vivid picture of an emotionally abusive relationship.

Fitchuk and Bryson share co-production credits with Edwards, and together the trio combine the lush textures of her Voyageur-era sound with the roots-rock sensibility of earlier material. Lead single “Options Open” – which started out embracing the giddy new-love rush of the early days of a relationship, only to fold back and celebrate the self when that relationship went sour – has the bright, poppy bounce of Fitchuk’s work with Morris or Musgraves, but the acerbic bite of the lyrics is Edwards’ own: “I swore I wouldn’t go near you with a ten-foot pole,” she sings, “but I’m holding up a mirror, we look so sweet.” Fitchuk also oversees, and plays brooding piano on “Ashes To Ashes”, a memento mori dedicated to a Quitters customer and friend, punctuated by sombre backing vocal from Courtney Marie Andrews and an emotive banjo solo from Todd Lombardo.

Bryson, who Edwards credits with “making me feel safe” as she navigated a return to recording that coincided with her exit from the abusive relationship that casts a shadow over some of the album’s more gut-wrenching tracks, shares production credits on some of these darker songs. They include “Feelings Fade”, a “parting middle finger” recorded in one raw vocal take, haunted by Kinley Dowling’s string arrangements and Aaron Goldstein’s pedal steel; “Hard On Everyone”, on which you can hear the daily microaggressions and anxieties of abuse build and snowball until the song reaches a screaming, cathartic electric guitar avalanche; and Edwards’ “armour song” “Fool’s Ride”, on which she mocks romantic cliches, and herself, from the safety of her freedom.

But the story of this album is not of that one relationship, but of the “total freedom” of the title: freedom to watch the birds on the feeder in the garden as the sun comes up, in a life full of the love of good dogs and good people. “Birds On A Feeder” was one of the earliest songs written for the album, before the relationship that would change its meaning, here rearranged by Fitchuk from the version Edwards played him on his sofa. “Come on, spring, won’t you show yourself to me,” sings Edwards, her voice as deft as those birds in flight, as her powers reawaken.

Q&A

Kathleen Edwards on fans, friends, freedom…

What got you writing music again?

I give Maren Morris some credit for that. She reached out to say she was a fan of mine from my early records, and would I consider writing with her. I went to Nashville for a few days and did

this writing session, and

it ended up being the

spark that I needed.

What does ‘total freedom’ mean to you?

My original working title for the album was ‘Quitsville’, but Ian pushed me away from that. It’s really funny that the title comes from the song “Birds On A Feeder”. Not long after I wrote it, I got into a relationship with someone who ended up being an emotionally abusive person. When I finally realised what I was dealing with, I did it feeling incredible gratitude: that I had the strength of self to go, and to have cultivated a life with amazing friends around me who knew something was wrong. It felt like total fucking freedom.

And yet the album is ultimately very loving.

One of the things about taking a big break from music and doing something totally different was that it gave me a chance to reflect. The last thing I wanted to do when writing a record was have it be very angry and reflective of bad memories. I don’t

want to get on stage and

sing about that every night! So I just put it in that lens,

and it came pretty easily.

INTERVIEW: LISA-MARIE FERLA