“How old is 75?” Loudon Wainwright III asks near the end of his new album, Lifetime Achievement. There’s a rickety banjo strumming in the background as he answers his own rhetorical question: “So old you’re barely alive”. It lands like a punchline, but Wainwright tempers that levity with...

“How old is 75?” Loudon Wainwright III asks near the end of his new album, Lifetime Achievement. There’s a rickety banjo strumming in the background as he answers his own rhetorical question: “So old you’re barely alive”. It lands like a punchline, but Wainwright tempers that levity with an almost unbearable gravity. On the verses to “How Old Is 75?” he notes that he’s already outlived his mother by one year and Loudon II by 13. What does that signify? Nothing really. It’s just the math of mortality, which measures the quantity but not the quality of years: “With our allotted amounts, what gets done is what counts”, he sings over strings that quiver and quake. “Was it time wasted or was it well spent?”

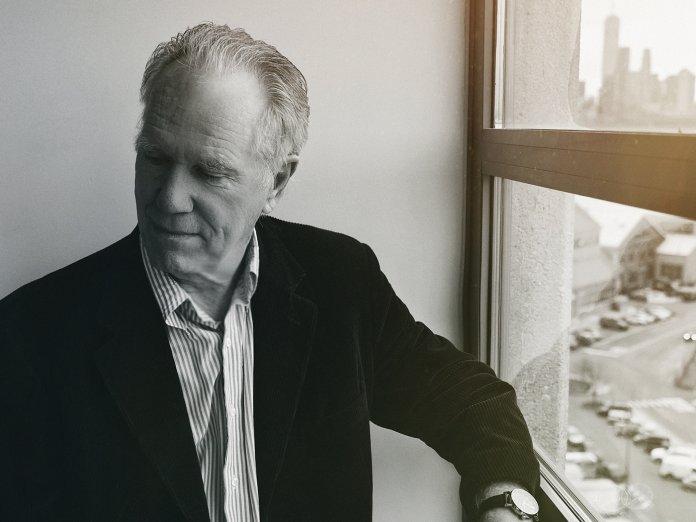

It’s not necessarily a new sentiment, but Wainwright delivers it in a way that makes it sound like wisdom passed down from generation to generation, from artist to listener. And what has he done with his own allotted amount? A lot, it turns out. In addition to landing memorable roles in films (The Aviator, Knocked Up) and sitcoms (M*A*S*H, Parks & Recreation), he has released 31 studio albums in just over 50 years and penned thousands of songs, one of which was a hit (1972’s “Dead Skunk”) and one of which remains perfect (1973’s “The Swimming Song”). Even more than any of the other so-called “new Dylans” of the late ’60s and early ’70s, Wainwright defined himself as a writer both profoundly funny and profoundly sad, who often uses a joke to convey the tragedy of a situation.

That ability has made him such a vital artist so late in his life; he was something like an old man even when he was young, so he takes to the subject of ageing with grace and insight. He tested these waters on 2012’s Older Than My Old Man, but Lifetime Achievement embraces the folksier elements of his sound, paring the music down to guitar, banjo, occasionally a harmonica and even more occasionally a full band. Working with a crew of old friends and collaborators, Wainwright arranges these songs with just one or two instruments, which gives them a delicacy that can be wistful (“Fun & Free”), weirdly humorous (the playfully austere “It”), or heart-wrenching (“It Takes 2”). He delivers “One Wish” a cappella, with no other instrument obscuring the grain or the keening arc of his voice. He’s lost little power over the years, even if the song is about struggling to blow out his many, many birthday candles.

But Lifetime Achievement isn’t an album about growing old. Or, it’s not only an album about growing old. Without sounding curmudgeonly or misanthropic, Wainwright continues to write about his own alienation from other people, including and especially his own loved ones. Sometimes he has fun with it: “I need a family vacation, I mean a family vacation alone”, he sings on the Tolstoy– and Sartre-quoting “Fam Vac”, extolling the simple pleasure of “leaving the fucking family at home!” It would sound mean-spirited if they didn’t need a vacation from him, too. Age makes that alienation more acute, as though he’s uncomfortable wherever he is. On the motormouthed “Town & Country”, which swings like Mose Allison, he recounts a trip to New York and discovers that the hubbub that used to excite him now just frays his nerves. That song slides tidily into “Island”, which he wrote 40 years ago but only just now got around to recording. “Back on the mainland they’re going crazy, I’m too old for that insanity”, he sings, but also notes the tedium of island life. Is it a haven away from the hubbub, or a hell of boredom? Probably a little of both.

What age does offer him, however, is a new perspective on his life. Lifetime Achievement is an album about identifying and appreciating the things that are most important, that make life in the city or on the island worthwhile. For Wainwright, it’s family. It’s loved ones. It might even be us, his listeners. On the title track he surveys his shelves full of trophies and walls heavy with every award imaginable: “Trophies on my mantelpiece, citations on my wall”, he sings over a country two-step, “but who needs cash and prizes? What I achieved is you”. He never really says who “you” is. It might be a love song to his girlfriend, a fatherly ode to his kids, or maybe a paean to his fans. But that only makes his declaration sound all the more poignant, as though Wainwright is still figuring it all out while the clock ticks down.