On May 5, 1968, in Long Beach, California, Neil Young played his final show with Buffalo Springfield, a band he’d already left and re-joined at least twice. “I didn’t have a clue what I was going to do next,” he told me in 1989. This seemed unlikely. For someone with only a vague notion of what he was going to do, he moved decisively, quickly hiring Elliot Roberts as his manager. Roberts - on his way to becoming one of the most powerful people in the American music business - had worked briefly with the Springfield earlier in their last disputatious year together, before being sacked by Neil for playing golf when he should have been attending to the group’s multiple whims. Roberts now signed his new client to Reprise, where apart from a short and unhappy liaison with Geffen Records, Young would remain for the rest of his career. That summer, Neil started work on his first solo album. The next step was to get Young in front of an audience, to test their reactions. In November, with the release of his debut solo album, Neil Young, now looming, two shows were booked, at Canterbury House, part of the University Of Michigan. The gigs were recorded on two-track tape, and exactly 40 years later finally see the light of the proverbial day as Sugar Mountain. I think if I’d been there on either night, my first reaction would have been something akin to shock. From what I knew of him at the time, Young was by reputation surly and remote, inclined towards fractious discord. In pictures, he had a tendency to look sullen, a moody loner. What a flattening surprise, then, to hear him here sounding so, well, goofy, I suppose you’d say. Ten of the 23 tracks listed on Sugar Mountain are spoken word introductions, rambling asides, random observations, often hilarious anecdotes delivered in a youthfully high-pitched voice that he at one point makes fun of himself. This awe-shucks folksiness is thoroughly disarming, as no doubt intended. Down the years, Young’s played this part to serial perfection – the straw-chewing backwoods philosopher, the bucolic savant, plain-speaking, daffy but wise, Jimmy Stewart on his way to Washington as Mr Deeds. “I never plan anything,” he says at one point, sounding baffled by his present circumstance in front all these people, some of them calling out for Buffalo Springfield songs he thought no one had even heard. But how true, you wonder, is this? Among the Buffalo Springfield songs for which he was perhaps best known were elaborate patchworks like 'Mr Soul', 'Expecting To Fly' and 'Broken Arrow' (all featured here). These were post-Pepper sonic collages, painstakingly assembled during long hours of over-dubbing in the studio, which was also how much of Neil Young had been produced, a process that had left him by his own admission disenchanted. For these Canterbury Hall shows, though, there clearly would be no attempt to replicate the unreleased album’s dense arrangements, orchestral flourishes and gospel backing vocals. This is just Neil, his voice and guitar and 13 songs, six from his Buffalo Springfield days, four from the forthcoming album, the unrecorded 'Sugar Mountain', an exquisite version of 'Birds', a song that would appear on After The Goldrush, and a brief snippet of Winterlude that barely merits a track listing of its own. In virtually every instance, these solo versions are preferable to the originals, performed with a singular confidence that suggests he may already have realised how dated when it came out aspects of Neil Young would sound, the stereo panning and overlaying of studio effects giving it an ornate fussiness that sat uneasily in the mutating musical climate of the late 60s. What’s striking here is how cleverly Young by now had grasped the fundamental changes in American music essayed already by Dylan and The Band on John Wesley Harding and Music From Big Pink. The summer of 1968 had seen the assassinations of Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King. A season of riot had left cities on fire across the republic and Nixon was in the White House. Dark times were getting darker. It was as if the only legitimate response to more complicated times was a new kind of simplicity. And so the precocious psychedelic technician of those Springfield epics is calculatedly recast as a soulful solo voyager whose songs spoke without undue adornment of shared apprehensions, collective uncertainties. On songs like 'Sugar Mountain', 'If I Could Have Her Tonight' and 'I've Been Waiting For You', his vulnerability is something tangible and universal. On a quartet of great Springfield songs included here – 'Out Of My Mind', 'Mr Soul', 'Expecting To Fly', 'Broken Arrow' – he expresses among other things an uneasy discomfort with fame and its hollow trappings that places him on the side of the people he’s playing to, an unchallenged alliance. These songs and similarly intimate others like them were unquestionably personal. Young brilliantly, however, was able to make the ‘you’ of the songs not only the individual they initially were addressed to, but also the people who would shortly be buying his albums in their thousands and then millions. The ‘you’ in this instance being the plurality of his audience, spoken to as if in private conversation, with whom he shared mutual intimacies, feelings about love and loss in which his fans would increasingly hear aspects of themselves and what they were going through. One of the pivotal songs here, I think, is the surreal 'Last Trip To Tulsa', which as the closing track of Neil Young would be regarded by some as an aberration, too heavily indebted to Dylan, its solo acoustic setting at odds with the rest of the album. Now, of course, its impressionistic narrative – nightmarish, absurd, paranoid, awash with grim portent - can be heard as the precursor to masterpieces to come, like 'Ambulance Blues' or 'Thrasher' and even 'Ordinary People', that similarly took the pulse of the nation and its people. Sugar Mountain is a fascinating snapshot of Neil Young at a transitory moment in his long career, for which it also provides an indelible template. This is in many ways how he would sound for the next 40 years. At least, that is, when he wasn’t raging noisily with Crazy Horse, taking various detours into unadulterated country, winsome folk, synthesiser-pop, stylised rockabilly, big band R&B, grunge, electronic experimentalism, otherwise undermining convenient expectation or elsewhere meandering down the musical avenues that have at various times left fans baffled and at least one record company exasperated enough to want to sue him for not sounding enough like himself, when in fact for all this time he has sounded like no one at all but himself. ALLAN JONES

On May 5, 1968, in Long Beach, California, Neil Young played his final show with Buffalo Springfield, a band he’d already left and re-joined at least twice. “I didn’t have a clue what I was going to do next,” he told me in 1989. This seemed unlikely. For someone with only a vague notion of what he was going to do, he moved decisively, quickly hiring Elliot Roberts as his manager. Roberts – on his way to becoming one of the most powerful people in the American music business – had worked briefly with the Springfield earlier in their last disputatious year together, before being sacked by Neil for playing golf when he should have been attending to the group’s multiple whims. Roberts now signed his new client to Reprise, where apart from a short and unhappy liaison with Geffen Records, Young would remain for the rest of his career. That summer, Neil started work on his first solo album.

The next step was to get Young in front of an audience, to test their reactions. In November, with the release of his debut solo album, Neil Young, now looming, two shows were booked, at Canterbury House, part of the University Of Michigan. The gigs were recorded on two-track tape, and exactly 40 years later finally see the light of the proverbial day as Sugar Mountain.

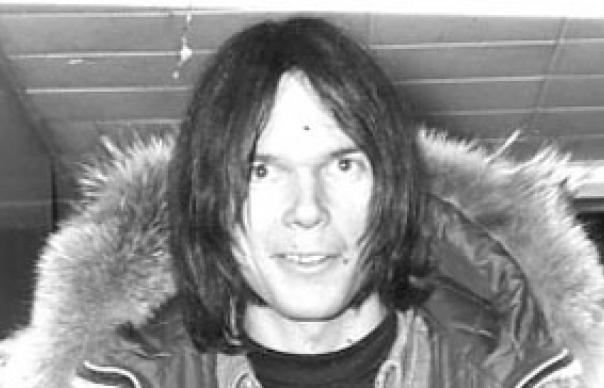

I think if I’d been there on either night, my first reaction would have been something akin to shock. From what I knew of him at the time, Young was by reputation surly and remote, inclined towards fractious discord. In pictures, he had a tendency to look sullen, a moody loner. What a flattening surprise, then, to hear him here sounding so, well, goofy, I suppose you’d say. Ten of the 23 tracks listed on Sugar Mountain are spoken word introductions, rambling asides, random observations, often hilarious anecdotes delivered in a youthfully high-pitched voice that he at one point makes fun of himself.

This awe-shucks folksiness is thoroughly disarming, as no doubt intended. Down the years, Young’s played this part to serial perfection – the straw-chewing backwoods philosopher, the bucolic savant, plain-speaking, daffy but wise, Jimmy Stewart on his way to Washington as Mr Deeds. “I never plan anything,” he says at one point, sounding baffled by his present circumstance in front all these people, some of them calling out for Buffalo Springfield songs he thought no one had even heard. But how true, you wonder, is this?

Among the Buffalo Springfield songs for which he was perhaps best known were elaborate patchworks like ‘Mr Soul’, ‘Expecting To Fly’ and ‘Broken Arrow’ (all featured here). These were post-Pepper sonic collages, painstakingly assembled during long hours of over-dubbing in the studio, which was also how much of Neil Young had been produced, a process that had left him by his own admission disenchanted. For these Canterbury Hall shows, though, there clearly would be no attempt to replicate the unreleased album’s dense arrangements, orchestral flourishes and gospel backing vocals.

This is just Neil, his voice and guitar and 13 songs, six from his Buffalo Springfield days, four from the forthcoming album, the unrecorded ‘Sugar Mountain’, an exquisite version of ‘Birds’, a song that would appear on After The Goldrush, and a brief snippet of Winterlude that barely merits a track listing of its own. In virtually every instance, these solo versions are preferable to the originals, performed with a singular confidence that suggests he may already have realised how dated when it came out aspects of Neil Young would sound, the stereo panning and overlaying of studio effects giving it an ornate fussiness that sat uneasily in the mutating musical climate of the late 60s.

What’s striking here is how cleverly Young by now had grasped the fundamental changes in American music essayed already by Dylan and The Band on John Wesley Harding and Music From Big Pink. The summer of 1968 had seen the assassinations of Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King. A season of riot had left cities on fire across the republic and Nixon was in the White House. Dark times were getting darker. It was as if the only legitimate response to more complicated times was a new kind of simplicity. And so the precocious psychedelic technician of those Springfield epics is calculatedly recast as a soulful solo voyager whose songs spoke without undue adornment of shared apprehensions, collective uncertainties.

On songs like ‘Sugar Mountain’, ‘If I Could Have Her Tonight’ and ‘I’ve Been Waiting For You’, his vulnerability is something tangible and universal. On a quartet of great Springfield songs included here – ‘Out Of My Mind’, ‘Mr Soul’, ‘Expecting To Fly’, ‘Broken Arrow’ – he expresses among other things an uneasy discomfort with fame and its hollow trappings that places him on the side of the people he’s playing to, an unchallenged alliance.

These songs and similarly intimate others like them were unquestionably personal. Young brilliantly, however, was able to make the ‘you’ of the songs not only the individual they initially were addressed to, but also the people who would shortly be buying his albums in their thousands and then millions. The ‘you’ in this instance being the plurality of his audience, spoken to as if in private conversation, with whom he shared mutual intimacies, feelings about love and loss in which his fans would increasingly hear aspects of themselves and what they were going through.

One of the pivotal songs here, I think, is the surreal ‘Last Trip To Tulsa’, which as the closing track of Neil Young would be regarded by some as an aberration, too heavily indebted to Dylan, its solo acoustic setting at odds with the rest of the album. Now, of course, its impressionistic narrative – nightmarish, absurd, paranoid, awash with grim portent – can be heard as the precursor to masterpieces to come, like ‘Ambulance Blues’ or ‘Thrasher’ and even ‘Ordinary People’, that similarly took the pulse of the nation and its people.

Sugar Mountain is a fascinating snapshot of Neil Young at a transitory moment in his long career, for which it also provides an indelible template. This is in many ways how he would sound for the next 40 years. At least, that is, when he wasn’t raging noisily with Crazy Horse, taking various detours into unadulterated country, winsome folk, synthesiser-pop, stylised rockabilly, big band R&B, grunge, electronic experimentalism, otherwise undermining convenient expectation or elsewhere meandering down the musical avenues that have at various times left fans baffled and at least one record company exasperated enough to want to sue him for not sounding enough like himself, when in fact for all this time he has sounded like no one at all but himself.

ALLAN JONES