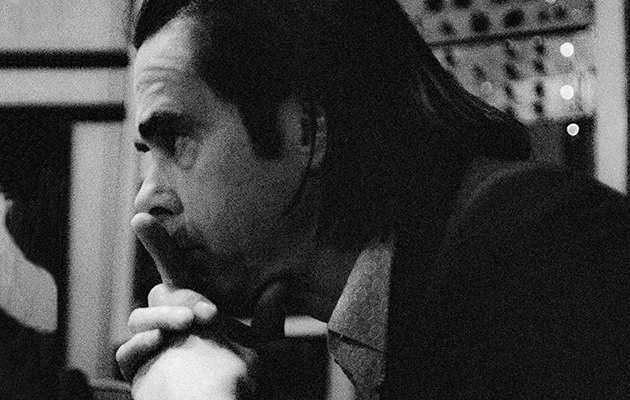

It’s tempting, when a record unfolds like a sermon, to concentrate on the words. And it’s true: on Ghosteen, Nick Cave has surpassed himself, redefining the shape and purpose of his writing. By conventional standards, these aren’t songs at all. They’re ruminations, fairy stories, misremember...

It’s tempting, when a record unfolds like a sermon, to concentrate on the words. And it’s true: on Ghosteen, Nick Cave has surpassed himself, redefining the shape and purpose of his writing. By conventional standards, these aren’t songs at all. They’re ruminations, fairy stories, misremembered dreams, visions. They scarcely bother with the formalities. There are few choruses, just occasional repetitions of phrases or lines: “I think they’re singing to be free,” or “It’s a long way to find peace of mind.”

What is it about? Faith mostly, death often, and the moving walkways that transport people between those unmappable destinations. Cave has more questions than answers, but he frames them in such a way that the indeterminate nature of things becomes the point, and even a cause of comfort. Beyond that, he’s celebrating the purpose of songs themselves, as in the opening track, “Spinning Song”, a swirling, wheezy thing that squeezes a jelly-haired Elvis into a strange parable owing as much to Enid Blyton’s Faraway Tree as it does to the Old Testament.

It’s possible, of course, that the song is even more self-involved than that, because it is a song about a song. Let’s play along, and imagine that the root of this mystery is Cave’s “Tupelo”, that ferocious anthem in which the birth of the King became an elemental act of Creation. “Tupelo” has the manners of a Cave from a different church, the black rain, the sandman, the eggless hen, the crowless cock. But listen to him now, on “Spinning Song”. “Once there was a song,” he murmurs, “the song yearned to be sung.” And by the end of the recitation, after this black-jelly Elvis King has crashed into Vegas and broken the heart of his queen “like a vow”, and a feather has spun up into the sky, Cave is addressing the listener directly. “And you’re sitting at the kitchen table, listening to the radio…” It would, of course, take a bold radio station to play this extraordinary tune: “Spinning Song” is not designed for heavy rotation. But wait, hold that computerised playlist, the singer is delivering the goods, right at the end: “And I love you,” he is singing. “Peace will come.”

Those are the words, but as always, the Bad Seeds have evolved musically. On Push The Sky Away and Skeleton Tree, they adapted to Cave’s monochromatic demeanour, colourising the backgrounds with more subtlety, less violence. Skeleton Tree in particular was unvarnished, medium rare, and Ghosteen continues in that vein. It is raw, but also synthetic. There are a number of very long songs, verbal rambles, but the music fills in, disturbing the melancholy of Cave’s piano with static interruptions that owe as much to Cave and Warren Ellis’s film soundtracks as they do to the Bad Seeds’ more conventional songcraft. On the title track, a 12-minute epic that references The Moony Man (a Japanese folk tale adapted for manga with added rocketships) there are echoes of Bowie’s Low, but also of the way Bill Fay channels nagging introspection into songs that have the yearning, the humility and the persuasive power of hymns.

All the Bad Seeds are credited, but it’s hard to get beyond the keyboards. Both Cave and Ellis are credited on synthesiser, and both do backing vocals. Ellis adds loops, flute and violin. None of which prepares you for the sound that they make. Those synths sound retro rather than futuristic, and the clips of reversed vocals give the whole thing the aura of a transmission from a distressed planet. If it were a book it would be Michel Faber’s The Book Of Strange New Things. But as these disturbances are cinematic, it’s hard to escape the orbit of David Lynch.

Of course, there is no pastiche-ing here, no ironic Orbison. The Bad Seeds do not play no rock’n’roll. Cave’s atmospheres are too airless for that. But there are jarring moments, neon-candy lightning flashes in the black ambience. Take the moment on “Ghosteen” where Cave sings “dancing, dancing all around” and the song suddenly swirls and reboots itself. “Here we go,” Cave says quietly, and the tune turns a page, and out of the turbulence comes a verse about the fairytale Three Bears (Goldilocks is notable by her absence). Why the Three Bears? Because fairytales are nasty and brutal, tutoring caution even as they comfort and entertain. And because Ghosteen has at its centre a dead child, a spirit or a little ghost, who sometimes narrates. In this context, the childish presence is wise, and is trying to soothe the pain of those who are left behind, so the imagery is inverted. Childishness becomes an invitation to wonder and to hope, and to live without concern for shortening horizons. “And baby bear,” Cave sings, prompting thoughts of Iggle Piggle’s journey at the conclusion of every episode of In The Night Garden, “he’s gone to the moon in a boat.”

Cave’s life has been marked by personal tragedy, and his recent work – his embrace of the essential decency of the crowd in his live shows, his emergence as an agony uncle to confused souls on his Red Hand Files Q&As – is usually viewed in that light. Nothing changes that, and there’s no escaping the profound darkness that envelops Ghosteen. You could hang autobiographical intent on the beautiful “Waiting For You”, which drapes a sense of loss and anticipation over a song that is as painful as it is literally dreadful. The singer drives through the night to a beach, waiting for someone to return. By the end, the exhausted narrator is encountering a Jesus freak on the streets, saying, “He is returning.” Cave concludes: “Well, sometimes a little bit of faith can go a long way.” And what of “Sun Forest”, a gorgeous, melancholy thing, apparently about a child’s ascension to heaven, punctuated by images of crucifixion, burning horses, black butterflies, beautiful green eyes, and the child beaming back a message of hope: “I am here beside you, look for me in the sun”?

“Ghosteen Speaks” is no less haunted, no less haunting. The narrator, at the end, is a spirit trying to make sense of their own funeral. “I am beside you,” they sing, “look for me,” before wondering about the purpose of the ceremony. Why are these people gathered together? “I think they’re singing to be free… to be beside me.”

You could make all of this about the singer’s misfortunes. But that would be reductive, and a shame, because Cave’s journey on Ghosteen – by boat, by ominous train, by car or heavenly staircase – is a grand tour in search of common ground. He is looking for the universal, with or without Jesus. His version of faith includes the bald observation in “Fireflies” that we are no more than “photons released from a star”.

It is, perhaps, a tough sort of faith that concludes that “there is no order here and nothing can be planned”. But the beauty of Ghosteen is the way it inhabits the darkness and still manages to harvest optimism. It is extreme stuff, singular in its design, ruthless in its execution. At the end, in “Leviathan”, Cave comes close to delivering a chorus, albeit in a song that flickers like a hallucinatory dream. There is a kid with a bad face at the window, a wild cougar killing by day, a house in the hills with a tear-shaped pool. “Everybody’s losing somebody,” Cave sings. “It’s a long way to find peace of mind.”