The self-styled ‘World’s Oldest Teenager’ nearly cost Stax Records several million dollars. During Rufus Thomas’ set at Wattstax – the label’s epochal 1972 all-dayer in the Watts neighbourhood of Los Angeles – the crowd at the Memorial Coliseum rushed the field and started dancing the ...

The self-styled ‘World’s Oldest Teenager’ nearly cost Stax Records several million dollars. During Rufus Thomas’ set at Wattstax – the label’s epochal 1972 all-dayer in the Watts neighbourhood of Los Angeles – the crowd at the Memorial Coliseum rushed the field and started dancing the funky chicken. Clad in a bright pink suit and his signature white go-go boots, Thomas beamed as the throng twisted and shimmied, but he soon backpedalled and began trying to shoo the spectators back to their seats. What followed was a masterclass in crowd control, as he threw out rhyming appeals for calm (“As soon as you get in the stands, then you’re gonna see the ‘Funky Chicken’ man!”) and even mercilessly roasted one particular straggler (“He don’t mean to be mean, he just wants to be seen”).

Neither the 1973 Wattstax documentary nor the pair of live albums that followed offer much in the way of explanation for Thomas’ sudden change of heart. In order to rent Memorial Coliseum, however, Stax had to take out a pricey insurance policy on the turf, which meant thousands of dancers trampling it down might have left the label on the hook for expensive repairs. On this new mammoth 50th-anniversary reissue, where we finally get to hear almost every second of the concert played out in real time, emcee John KaSandra explains it to the audience: “It would be beautiful if we would respect each other and take our seats. We just can’t afford to let it happen like this.” Once the field is finally vacated, Thomas continues his set, crossing his fingers that the crowd don’t want to “Do The Funky Penguin” quite as rowdily as the funky chicken.

It’s a strange, unscripted comedy within the larger story of Wattstax, an event made all the more remarkable for the complete absence of law enforcement (police were stationed outside the stadium but not allowed inside). Running to a dozen CDs featuring more than half a day’s worth of music, Soul’d Out: The Complete Wattstax Collection is exhaustive in the best way possible, emphasising the logistical nightmares of hosting such a big event but also putting listeners right there in the stadium. It brings these old performances into the present moment to let the sweet soul music and the message of Black Pride resonate across time.

In the years leading up to the festival, Stax had survived a series of almost fatal setbacks. In December 1967, Otis Redding and most of The Bar-Kays died when their plane crashed in rural Wisconsin. The next year Atlantic Records refused to renew its distribution deal and absconded with Stax’s entire back catalogue. Label president Al Bell came up with an audacious plan to flood the market with new releases by its remaining artists. The scheme worked, largely because of Isaac Hayes’ Hot Buttered Soul. Sprawling and eloquently orchestrated, that album not only commanded the R&B charts for several years but also signalled a shift in soul music for the new decade.

Now not just surviving but expanding at an alarming rate, the label sought to secure a foothold in the West Coast market. Watts was the ideal setting for a music festival: just seven years before, the neighbourhood was the scene of a week-long demonstration popularly known as the Watts Riots or the Watts Rebellion, and the annual Watts Cultural Festival had helped solidify the growing Black Pride movement. Stax sent nearly its entire roster out to LA, but only charged $1 for tickets: cheap enough that even the poorest members of the community could attend. The crowd ultimately exceeded 110,000 people.

Just before 3pm on August 20, 1972, Detroit singer Kim Weston opened the ceremonies by performing first the national anthem and then “Lift Every Voice And Sing”, known as the black national anthem. The first 13 of the 28 acts would only get one song each, which meant that setup and teardown often took longer than the music itself. But those brief sets reveal the rich diversity of ’70s Stax, whose roster included secular soul singers like Eddie Floyd, rock bands like The Rance Allen Group, funk acts like The Bar-Kays, bluesmen like Albert King, and lots and lots of gospel. Granted, sometimes all that distinguished the church acts from the club acts was the subject matter of their songs: Louise McCord delivers a mighty “Better Get A Move On” with all the urgent, pleading energy that Floyd brings to his 1966 hit “Knock On Wood”.

The logistical nightmare of managing so many different acts inadvertently created some of the best music here, as well as some of the most compelling footage in the Wattstax film (which was directed by Mel Stuart, fresh off Willy Wonka & The Chocolate Factory). After hours of delays and with a curfew looming, many of the later acts on the bill were cancelled. The Emotions got the hook right as they were preparing to take the stage, so instead recorded a short set at the Friendlywill Baptist Church in Watts. Likewise, Johnnie Taylor didn’t get to perform at the Coliseum, but Stax did film his sweaty performance at the local Summit Club. Those compensations give both the film and this box set a refreshing change of scenery, which shows how soul lived and breathed in Watts and, by extension, throughout America.

Perhaps no act better represented that idea than The Staple Singers, the Chicago family who brought gospel into the mainstream and combined it with folk, R&B, rock and blues. Originally they weren’t included on the bill, as they had a steady gig opening for Sammy Davis Jr in Las Vegas. But when he cancelled his show that day to campaign for Richard Nixon, the Staples hopped on a last-minute flight for a surprise set. “Respect Yourself” sounds barbed in this setting, with Pops admonishing white listeners to “take the sheet off your face, boy, it’s a brand-new day!” He sings as though bigotry is at heart a form of self-negation, that shedding such hatred would benefit whites as well as blacks. On the other hand, “I’ll Take You There” bristles with fresh optimism, as Mavis sings to fill the entire stadium. She sounds like she’s trying to single-handedly carry everyone into a brighter future.

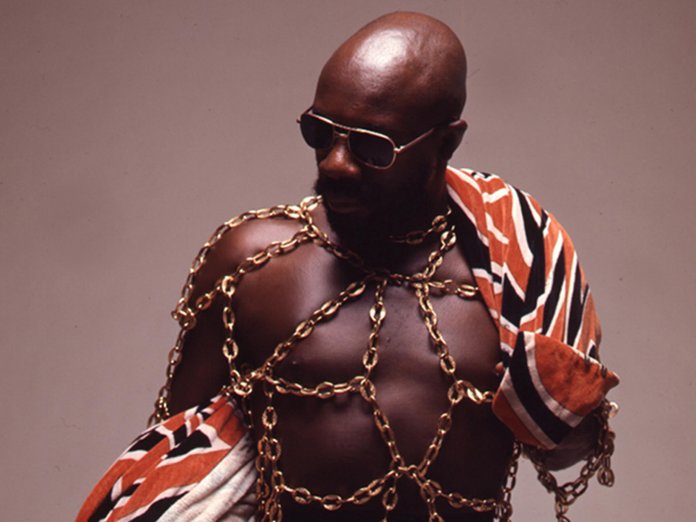

Headlining Wattstax was Isaac Hayes, not only the most popular act on the label but at this point arguably one of the biggest stars in the world. Earlier in 1972, his “Theme From Shaft” won the Oscar for Best Original Song, which made him the first black artist to win a non-acting Academy Award. He took the stage at Memorial Coliseum sporting a vest of gold chains, pink tights and black-and-white moonboots, cracking a wide smile when more than 100,000 people tell him to “shut yo’ mouth.” The film ends with “Soulsville”, a mournful ballad about how the ghetto can produce great art. While it’s a celebration of black creativity and perseverance, it’s a low-key, anticlimactic finale.

Fortunately, Soul’d Out restores his entire set: both versions of “Theme From Shaft”, a lush “Never Can Say Goodbye”, a version of “Your Love Is So Doggone Good” that’ll make you blush, and a harrowing medley of “Ain’t No Sunshine” and “Lonely Avenue”. Music, Hayes makes clear, isn’t something that’s only experienced at a big festival. It’s something listeners partied to on Saturday night and prayed with on Sunday morning. It was and remains a soundtrack to every aspect of life.