It’s fair to say that Amadou Bagayoko and Mariam Doumbia fit rather uncomfortably into world music. The pair, who met at a school for the blind in the Malian capital 36 years ago, gleefully admit to being as influenced by Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, Stevie Wonder, European techno and American hip hop as they are by the jeli griots of Mali. When they first visited Paris in the early 1990s, instead of being placed in the musical ghetto marked “musiques du monde”, their publishing company immediately got them to co-write with French rock stars like M. Ever since they’ve been marketed internationally as a pop group. They headline at stand-up rock venues to amazingly diverse audiences. They’ve played Lollapalooza and Latitude. They recorded the official FIFA theme for the 2006 World Cup. They’ve been produced by rebel French rock rocker Manu Chao. They even toured last year with the Scissor Sisters – a feat that, say, Salif Keita might have problems pulling off with dignity. More to the point, in a world where African artists are often expected to conform to nebulous tropes of “authenticity” and “rootsiness”, their music is thrillingly off-message, distinctly African but never particularly alien to ears raised on Western rock music. Listen to their earlier releases, like 1998’s Sou Ni Tilé or 1999’s MTje Ni Mousso and you’ll hear what sounds like a 1960s garage rock band trying to replicate Malian bajourou; the music that Booker T & The MGs might have made had Stax been uprooted from Memphis to Mali. It comes mixed with other loose ends thrown up by the African diaspora –wailing blues harmonicas, salsa drums, chicken-scratch funk guitars and delicate touches of dub production into their fluid Afro-Stax hybrid. While most of Welcome To Mali is helmed by Marc-Antoine Moreau and Lauren Jais, who have produced and engineered most of A&M’s previous albums, the key guest production slot comes from the seemingly omnipresent Damon Albarn, who produced and co-wrote the lead track “Sabali”. It represents a big change in direction for A&M – Albarn takes the plinky plonky, oriental-sounding computer-game keyboard riffs familiar from his Monkey opera and several Gorillaz tracks and sets it against Mariam’s eerily high-pitched vocal, assisted by a Vocoder. The result sounds like Dizzee Rascal and Giorgio Moroder teaming up with Asha Bhosle on a Bollywood soundtrack. The minimal, electronic approach continues on other tracks, like “Ce N’est Pas Bon” (where Albarn contributes marimba-like keyboard patterns and sets them against heavily reverbed guitars) as well the hypnotic “Magosa” (all clippety-cloppety drums, beer-bottle flutes and serpentine bass clarinet). It also influences “Djama”, a re-recording of a recently unearthed track first recorded in 1979, which is turned into a terrific slice of dancehall reggae, complete with rolling Farfisa organ and those synthesized “pongs” that you get in disco records. Other collaborators also make their mark. K’Naan, the Somali-born, Toronto-raised rapper, provides the lead vocal on the tremendous “Africa”, a Motown-inspired love song to a continent described by K’Naan as “the original west coast/east coast collaboration”. Juan Rozoff – a Todd Rundgren-ish French multi-instrumentalist and singer – turns “Je Te Kiffe” into a funky shuffle, while Nigerian guitarist Keziah Jones adds a suitably Fela-ish vibe to the title track and to the militantly funky Afrobeat-inspired “Unissons Nous”. Elsewhere, it’s not so much a change of direction, more of an upgrade from previous albums. Where Manu Chao might have smoothed off some of the rough edges during his spell as co-producer, this album positively celebrates those grungier moments. Central to A&M’s work has always been Amadou’s guitar style, one which appears to replicate the tumbling, elegant sound of the kora on a distorted guitar. Where so much guitar playing from the around the African continent – jit-jive, hi-life, palm wine, township jive – sounds spangly and bright, Amadou’s slithering, grinding guitar riffs sound dark and spiky, the missing link between Ali Farka Touré and Steve Cropper. Check out the grungy 6/8 rockabilly of “Bozos”, the syncopated boogie of “Compagnon de la Vie”, or “Djuru”, where Amadou’s twangy R&B riffs mesh with Toumani Diabate’s distinctive kora playing. The oddest and most uncharacteristic track on the album, however, is also the best. “I Follow You” sees Amadou singing a love song for Mariam in wonderfully guileless, faltering English. Amadou’s endearingly clumsy lyrics (“when you go to school/I follow you/when you go to work/I follow you/when you go to play/I follow you”) are set to a soaring, string drenched backing. It’s one of the most beautifully and passionate love-letters you’re likely to hear. JOHN LEWIS UNCUT Q&A: Amadou Bagayoko Where did you record the album? It was recorded in Paris, Bamako, Dakar and London over the course of a year. It’s a global production! But we still live in Mali – it’s quite important that we haven’t moved to France. How did you hook up with Damon Albarn? We met him in Mali, Congo and London, and we also joined his Africa Express project, where Damon helped African music and African musicians by putting a focus on them in Britain. He is a very interesting and constructive person to work with. He is the kind of guy who is always trying to find solutions, to find out the reasons behind things. How do you and Mariam write songs? We work by ourselves and also with each other. Sometimes we will work on each others songs. We start vocally with melodies, unaccompanied. Then we try those melodies on the guitars and they start to change. Then in the studio we arrange it further and move the music in different directions. You sing in English on a couple of tracks – does that feel weird? Yes! But singing in French also felt weird when we first did that. We always used to sing in Bambara. We used French to make sure that they understood what we were singing. Now we would like English-speaking people to understand us. It’s not a large vocabulary but our heart is in it. I am even more shy than usual singing in English! INTERVIEW: JOHN LEWIS For more album reviews, click here for the UNCUT music archive

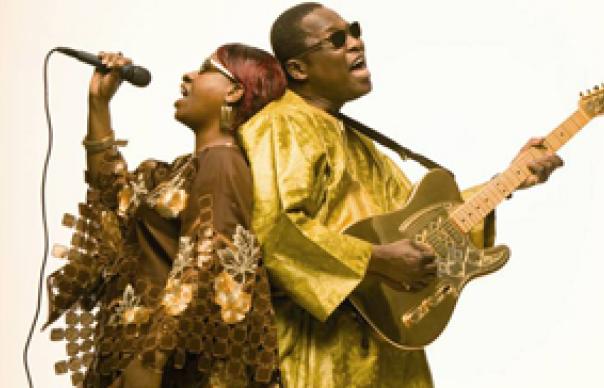

It’s fair to say that Amadou Bagayoko and Mariam Doumbia fit rather uncomfortably into world music. The pair, who met at a school for the blind in the Malian capital 36 years ago, gleefully admit to being as influenced by Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, Stevie Wonder, European techno and American hip hop as they are by the jeli griots of Mali.

When they first visited Paris in the early 1990s, instead of being placed in the musical ghetto marked “musiques du monde”, their publishing company immediately got them to co-write with French rock stars like M. Ever since they’ve been marketed internationally as a pop group. They headline at stand-up rock venues to amazingly diverse audiences. They’ve played Lollapalooza and Latitude. They recorded the official FIFA theme for the 2006 World Cup. They’ve been produced by rebel French rock rocker Manu Chao. They even toured last year with the Scissor Sisters – a feat that, say, Salif Keita might have problems pulling off with dignity.

More to the point, in a world where African artists are often expected to conform to nebulous tropes of “authenticity” and “rootsiness”, their music is thrillingly off-message, distinctly African but never particularly alien to ears raised on Western rock music. Listen to their earlier releases, like 1998’s Sou Ni Tilé or 1999’s MTje Ni Mousso and you’ll hear what sounds like a 1960s garage rock band trying to replicate Malian bajourou; the music that Booker T & The MGs might have made had Stax been uprooted from Memphis to Mali. It comes mixed with other loose ends thrown up by the African diaspora –wailing blues harmonicas, salsa drums, chicken-scratch funk guitars and delicate touches of dub production into their fluid Afro-Stax hybrid.

While most of Welcome To Mali is helmed by Marc-Antoine Moreau and Lauren Jais, who have produced and engineered most of A&M’s previous albums, the key guest production slot comes from the seemingly omnipresent Damon Albarn, who produced and co-wrote the lead track “Sabali”. It represents a big change in direction for A&M – Albarn takes the plinky plonky, oriental-sounding computer-game keyboard riffs familiar from his Monkey opera and several Gorillaz tracks and sets it against Mariam’s eerily high-pitched vocal, assisted by a Vocoder. The result sounds like Dizzee Rascal and Giorgio Moroder teaming up with Asha Bhosle on a Bollywood soundtrack.

The minimal, electronic approach continues on other tracks, like “Ce N’est Pas Bon” (where Albarn contributes marimba-like keyboard patterns and sets them against heavily reverbed guitars) as well the hypnotic “Magosa” (all clippety-cloppety drums, beer-bottle flutes and serpentine bass clarinet). It also influences “Djama”, a re-recording of a recently unearthed track first recorded in 1979, which is turned into a terrific slice of dancehall reggae, complete with rolling Farfisa organ and those synthesized “pongs” that you get in disco records.

Other collaborators also make their mark. K’Naan, the Somali-born, Toronto-raised rapper, provides the lead vocal on the tremendous “Africa”, a Motown-inspired love song to a continent described by K’Naan as “the original west coast/east coast collaboration”. Juan Rozoff – a Todd Rundgren-ish French multi-instrumentalist and singer – turns “Je Te Kiffe” into a funky shuffle, while Nigerian guitarist Keziah Jones adds a suitably Fela-ish vibe to the title track and to the militantly funky Afrobeat-inspired “Unissons Nous”.

Elsewhere, it’s not so much a change of direction, more of an upgrade from previous albums. Where Manu Chao might have smoothed off some of the rough edges during his spell as co-producer, this album positively celebrates those grungier moments. Central to A&M’s work has always been Amadou’s guitar style, one which appears to replicate the tumbling, elegant sound of the kora on a distorted guitar. Where so much guitar playing from the around the African continent – jit-jive, hi-life, palm wine, township jive – sounds spangly and bright, Amadou’s slithering, grinding guitar riffs sound dark and spiky, the missing link between Ali Farka Touré and Steve Cropper. Check out the grungy 6/8 rockabilly of “Bozos”, the syncopated boogie of “Compagnon de la Vie”, or “Djuru”, where Amadou’s twangy R&B riffs mesh with Toumani Diabate’s distinctive kora playing.

The oddest and most uncharacteristic track on the album, however, is also the best. “I Follow You” sees Amadou singing a love song for Mariam in wonderfully guileless, faltering English. Amadou’s endearingly clumsy lyrics (“when you go to school/I follow you/when you go to work/I follow you/when you go to play/I follow you”) are set to a soaring, string drenched backing. It’s one of the most beautifully and passionate love-letters you’re likely to hear.

JOHN LEWIS

UNCUT Q&A: Amadou Bagayoko

Where did you record the album?

It was recorded in Paris, Bamako, Dakar and London over the course of a year. It’s a global production! But we still live in Mali – it’s quite important that we haven’t moved to France.

How did you hook up with Damon Albarn?

We met him in Mali, Congo and London, and we also joined his Africa Express project, where Damon helped African music and African musicians by putting a focus on them in Britain. He is a very interesting and constructive person to work with. He is the kind of guy who is always trying to find solutions, to find out the reasons behind things.

How do you and Mariam write songs?

We work by ourselves and also with each other. Sometimes we will work on each others songs. We start vocally with melodies, unaccompanied. Then we try those melodies on the guitars and they start to change. Then in the studio we arrange it further and move the music in different directions.

You sing in English on a couple of tracks – does that feel weird?

Yes! But singing in French also felt weird when we first did that. We always used to sing in Bambara. We used French to make sure that they understood what we were singing. Now we would like English-speaking people to understand us. It’s not a large vocabulary but our heart is in it. I am even more shy than usual singing in English!

INTERVIEW: JOHN LEWIS

For more album reviews, click here for the UNCUT music archive