The follow-up to Hadestown seals Mitchell’s pre-eminence... What’s the next stop after Hadestown? Anais Mitchell’s brilliantly realised 2010 ‘folk opera’ elevated her from the ever swollen ranks of classy U.S. songwriters to recognition as a true original. When she matched the acclaim for her ambitious creation – a re-telling of the myth of Orpheus and Persephone set in depression-era America – with engaging performances as both a solo act and with a full ensemble cast, it was clear a vibrant new voice had arrived. Mitchell’s high, spiky voice is not everyone’s idea of a classic, but it’s immediate and insistent. Most importantly, it’s that of a poet, spraying out phrases that first capture attention and then resonate. “Your daddy didn’t leave a will/He left a shovel and a hole to fill,” (from “He Did”) is a line that Gillian Welch would surely be glad to own. Something of Mitchell’s qualities were apparent on the albums she made in her twenties, 2004’s Hymns For The Exiled and 2007’s The Brightness, the latter after she was signed by Ani Di Franco, one of her early influences. Collections of mostly earnest, confessional songs delivered to acoustic guitar, neither record prepared us for the character-led drama and layered arrangements of Hadestown, or its deft update of mythology. Young Man In America follows on in convincing style. With Hadestown producer Todd Sickafoose again at the helm and an array of seasoned players providing backings, this is a more complex musical creation than Mitchell’s trade description as ‘singer-songwriter’ suggests, full of delicately played fiddles, mandolins, squeezeboxes and guitars, with the odd touch of rhythmic thunder. Its eleven songs are likewise far removed from forlorn navel-gazing, and instead belong to characters inhabiting a semi-mythical America, the kind of frontier landscape conjured by Dylan’s John Wesley Harding, which is evoked in language that’s part modern, part drawn from folk tradition. If Young Man... isn’t quite a concept album, its songs are strongly themed, revolving around issues of children and parenting. The title track is central, conjuring a boy who “arrived like a cannonball” and who will “blow like a hurricane/Everyone will know my name”. With a father who was “a repo man, put me out on the street”, this is the cry of an avenging orphan. The shadow of the father likewise hangs over the delicately picked “He Did”, describing a man who loved his offspring and “kept a blue-grey eye on you” but “couldn’t draw you near to him”. “Tailor” turns the tables, dealing with a child’s desire to please. With its gentle air and almost singalong chorus, it has something of a kiddy’s song about it, yet it ends on a desolate note, with the apparently orphaned singer wondering “There isn’t anyone to say if I’m a diamond or a dime a dozen. Who am I?” Other songs are less specific. The sprightly “Venus” addresses the glories of womanhood in a way that might refer to either mother or beauteous lover – “My love moved inside me/A snake waked up in my body” – while “You Are Forgiven”, meandering against a soft chorus of voices and horns, is likewise ambiguous. The one clearly romantic song is “Ships”, whose dreamy atmosphere has an abandoned sailor’s woman longing for her departed man, though whether he’s gone on a voyage of discovery or to someone else isn’t spelt out. Then there’s “Shepherd”. Set to rippling guitars, it’s a tale of a shepherd torn between saving his flock and farm or being with his wife at childbirth. It turns out to be inspired by a story written by Mitchell’s father, whose picture at age 30 is on the cover of Young Man..., and whom Mitchell admits is “a presence” on the album. Mitchell grew up on her parents’ farm in Vermont, and although the tale is imaginary, she insists that “the sheep are real”. As much is true of the deep emotional currents captured on a remarkable, genre-defying album. Neil Spencer Q&A Anais Mitchell Is this another concept album? It’s not a narrative like Hadestown, more a meditation. The title track seems like an allegory for the USA. It’s certainly influenced by the recession. The idea of a father who is a repoman came from seeing people turned out on the streets with their furniture. Other lines got thrown way; people unable to pay for medicine, or spending Christmas on a Greyhound bus. There’s a feeling the American is something of an orphan, that we can’t trust we’re going to be taken care of. Any event in your life that’s triggered its themes? A few years ago my dad lost his dad, and to see his loss was very affecting. “Shepherd” is based on a story he wrote when he was my age, 30 - he’s a writer and I’m a writer. I’m not a mother yet and I’m not being parented. In the old days that time in life wasn’t long but nowadays it’s stretched out. Maybe I’m longing for a place I’m not at. What’s next? I’m working on a collection of British Child Ballads. That has affected the way I write. I love the sound of that old English language and the mix with US frontier language. INTERVIEW: NEIL SPENCER Please fill in our quick survey about the relaunched Uncut – and you could win a 12 month subscription to the magazine. Click here to see the survey. Thanks!

The follow-up to Hadestown seals Mitchell’s pre-eminence…

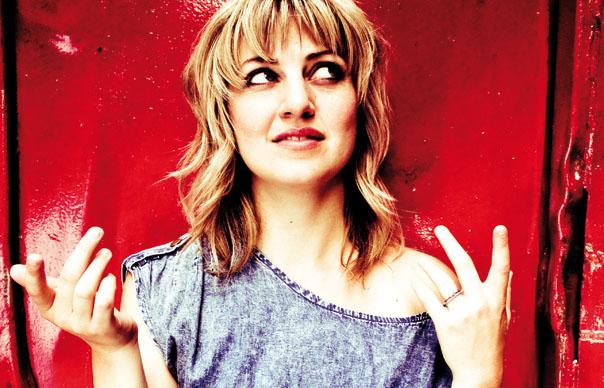

What’s the next stop after Hadestown? Anais Mitchell’s brilliantly realised 2010 ‘folk opera’ elevated her from the ever swollen ranks of classy U.S. songwriters to recognition as a true original. When she matched the acclaim for her ambitious creation – a re-telling of the myth of Orpheus and Persephone set in depression-era America – with engaging performances as both a solo act and with a full ensemble cast, it was clear a vibrant new voice had arrived.

Mitchell’s high, spiky voice is not everyone’s idea of a classic, but it’s immediate and insistent. Most importantly, it’s that of a poet, spraying out phrases that first capture attention and then resonate. “Your daddy didn’t leave a will/He left a shovel and a hole to fill,” (from “He Did”) is a line that Gillian Welch would surely be glad to own.

Something of Mitchell’s qualities were apparent on the albums she made in her twenties, 2004’s Hymns For The Exiled and 2007’s The Brightness, the latter after she was signed by Ani Di Franco, one of her early influences. Collections of mostly earnest, confessional songs delivered to acoustic guitar, neither record prepared us for the character-led drama and layered arrangements of Hadestown, or its deft update of mythology.

Young Man In America follows on in convincing style. With Hadestown producer Todd Sickafoose again at the helm and an array of seasoned players providing backings, this is a more complex musical creation than Mitchell’s trade description as ‘singer-songwriter’ suggests, full of delicately played fiddles, mandolins, squeezeboxes and guitars, with the odd touch of rhythmic thunder. Its eleven songs are likewise far removed from forlorn navel-gazing, and instead belong to characters inhabiting a semi-mythical America, the kind of frontier landscape conjured by Dylan’s John Wesley Harding, which is evoked in language that’s part modern, part drawn from folk tradition.

If Young Man… isn’t quite a concept album, its songs are strongly themed, revolving around issues of children and parenting. The title track is central, conjuring a boy who “arrived like a cannonball” and who will “blow like a hurricane/Everyone will know my name”. With a father who was “a repo man, put me out on the street”, this is the cry of an avenging orphan. The shadow of the father likewise hangs over the delicately picked “He Did”, describing a man who loved his offspring and “kept a blue-grey eye on you” but “couldn’t draw you near to him”.

“Tailor” turns the tables, dealing with a child’s desire to please. With its gentle air and almost singalong chorus, it has something of a kiddy’s song about it, yet it ends on a desolate note, with the apparently orphaned singer wondering “There isn’t anyone to say if I’m a diamond or a dime a dozen. Who am I?”

Other songs are less specific. The sprightly “Venus” addresses the glories of womanhood in a way that might refer to either mother or beauteous lover – “My love moved inside me/A snake waked up in my body” – while “You Are Forgiven”, meandering against a soft chorus of voices and horns, is likewise ambiguous. The one clearly romantic song is “Ships”, whose dreamy atmosphere has an abandoned sailor’s woman longing for her departed man, though whether he’s gone on a voyage of discovery or to someone else isn’t spelt out.

Then there’s “Shepherd”. Set to rippling guitars, it’s a tale of a shepherd torn between saving his flock and farm or being with his wife at childbirth. It turns out to be inspired by a story written by Mitchell’s father, whose picture at age 30 is on the cover of Young Man…, and whom Mitchell admits is “a presence” on the album. Mitchell grew up on her parents’ farm in Vermont, and although the tale is imaginary, she insists that “the sheep are real”. As much is true of the deep emotional currents captured on a remarkable, genre-defying album.

Neil Spencer

Q&A Anais Mitchell

Is this another concept album?

It’s not a narrative like Hadestown, more a meditation.

The title track seems like an allegory for the USA.

It’s certainly influenced by the recession. The idea of a father who is a repoman came from seeing people turned out on the streets with their furniture. Other lines got thrown way; people unable to pay for medicine, or spending Christmas on a Greyhound bus. There’s a feeling the American is something of an orphan, that we can’t trust we’re going to be taken care of.

Any event in your life that’s triggered its themes?

A few years ago my dad lost his dad, and to see his loss was very affecting. “Shepherd” is based on a story he wrote when he was my age, 30 – he’s a writer and I’m a writer. I’m not a mother yet and I’m not being parented. In the old days that time in life wasn’t long but nowadays it’s stretched out. Maybe I’m longing for a place I’m not at.

What’s next?

I’m working on a collection of British Child Ballads. That has affected the way I write. I love the sound of that old English language and the mix with US frontier language.

INTERVIEW: NEIL SPENCER

Please fill in our quick survey about the relaunched Uncut – and you could win a 12 month subscription to the magazine. Click here to see the survey. Thanks!