The LA maverick invokes Anglophile folk on first new album in six years... “Turn, turn away/From the sound of your own voice,” sings Beck towards the end of Morning Phase, his first new album in six years. Those lines serve as a pretty neat summary of his working methods during his hiatus, where he seemed to explore every possible musical avenue other than write and record an album of his own songs. First he took a back seat as producer for fellow travellers such as Thurston Moore and Stephen Malkmus, most strikingly and successfully crafting and co-writing Charlotte Gainsbourg’s IRM. Then there was the enjoyably ramshackle Record Club, where he assembled disparate like-minds – Liars, St Vincent, Devendra Bernhardt, Feist, members of Tortoise, Wilco and Os Mutantes – to record a version of a favourite album – The Velvet Underground & Nico, INXS’s Kick – in one day. Most satisfying – conceptually, artistically and in performance – there was 2012’s Song Reader: an album in the form of sheet music, a tribute to the lost American songbook from before recording, which culminated in a delirious, unhinged performance at the Barbican featuring interpretations from Jarvis Cocker, Franz Ferdinand and The Mighty Boosh. If the gap years were a deliberate attempt to recharge the batteries and to revive his muse, then by the climax of the Barbican show – leading his raggle-taggle troupe in a raucous singalong – he seemed a man revived. Right enough last year, unexpected one-off singles appeared – “Gimme”, “I Won’t Be Long” and best of all, the Animal Collective-ish “Defriended”. If Record Club seemed to gently establish him as a godfather of 21st-Century blog-rock, then every sign seemed to be that he was gradually re-emerging to reclaim his crown. Morning Phase isn’t quite such a bold return. Rather than lighting out for new territory or reaffirming his place as high-concept freakfolk/artpop conjuror, the new record returns to the Beck of Sea Change, the plangent, acoustic, confessional album he recorded in 2002 in the wake of his break-up with long-term girlfriend Leigh Limon. Though Beck himself seems reluctant to consider Morning Phase a companion piece or twisted sibling to the earlier recording, it does reassemble the same group of musicans – guitarists Smokey Hormel and Jason Falkner, keyboard player Roger Manning and drummer Joey Waronker. Morning Phase dawns with “Cycle”, an unsettling Arvo Part-y string drone – the first of a couple of orchestral interludes – before beginning in earnest with “Morning”. “Woke up this morning…” he keens – and here you might anticipate some lyrical dislocation, a monkey wrench in the genre mechanics but instead he continues faithfully, earnestly, “from a long night in the storm”. Like Sea Change, Morning Phase seems intent on pursuing emotional authenticity deep into plain speaking, and even cliché. His research into sheet-music history of the American songbook may even have heightened this commitment: elsewhere on the new record you find another track titled “Blue Moon” without the faintest wink of irony. Beck has talked about how he found inspiration for Morning Phase in the cosmic Caliornian music of his youth, the wild-honey harmonies of The Byrds and Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, and on “Morning” you hear a hint of the pie-eyed starsailing of Judee Sill. But elsewhere if you think of The Byrds you’re more likely to be put in mind of the desolate dawn chill of “Draft Morning”. The album is presented as a new dawn for Beck, but emotionally it feels still tied to the trauma that triggered Sea Change. After emerging from the storm, Beck continues, “Looked up this morning/Found the rose was full of thorns”. Furthermore, rather than California dreams, Morning Phase generally evokes a more wintry, Anglophile folk music. “Heart Is A Drum” distills the soundworld of Nick Drake’s Bryter Layter – the frosty clarity of the acoustic fingerpicking, the tinkling brook of piano and looming Robert Kirby orchestral cloudscape, here reprised by Beck’s father, David Campbell. “Turn Away” owes something to Simon & Garfunkel’s “The Sound Of Silence” while the closing “Waking Light” aspires to the interstellar bombast of Roger Waters’ Pink Floyd. Individually there are some wonderful songs on Morning Phase. “Blackbird Chain” is a small marvel, shuffling through time signatures like prime Lee Hazlewood, Smokey Hormel’s mercurial guitar flowering and then spiralling across “Country Down” as Beck sings of “a tiger rose growing through your prison floor”. But cumulatively Morning Phase can feel too consistent in mood and pace. The songs tread some well-worn melodic routes, and Beck’s thin but serviceable voice is dulled rather than bolstered when multitracked into harmony. “Unforgiven” distills some of the problems of the record. Over echo-laden electric piano chords Beck sings solemnly of driving into the night, into the afterglow, to somewhere unforgiven. In a way that seems somehow typical of Gen Xers (think of how Johnny Depp or Leo DiCaprio still seem boyish and unconvincing as leading men), Beck is unable to convincingly get into the saddle of this kind of mythic American deepsong – it feels forced and unconvincing, like someone trying to sing an octave too low. One of the more intriguing songs is “Wave”. It’s just Beck alone on an orchestral seascape, like Robert Redford in “All Is Lost”, singing atonally of “isolation”. The song was originally written for Charlotte Gainsbourg and it hints tantalisingly at some fresh, strange, latter-day Scott Walker horizons for Beck. Along with the preceding singles, and the talk of a second album already in the works, it makes you wonder if Morning Phase was selected as simply the most commercially tenable release for Beck to return with – a placeholder rather than statement of ambition. But this also highlights quandary that may have led to Beck’s six-year hiatus. Back in 2006, Uncut’s John Mulvey remarked on the irony that, for a supposed maverick, Beck had succumbed to routine: “He releases a hip-hop/pop/blues romp showcasing his post-modern hipster schtick. Then he follows it up with a faintly ethereal, largely straight-faced singer-songwriter album, helmed by Nigel Godrich.” As impressive as Morning Phase in places is, it doesn’t disturb this formula – even if it’s followed up by a wilder, stranger album. This division may make the records easier to market but it hobbles Beck’s antic muse. If the second act of his career is to be as arresting as the first, his problem is not so much to synthesise the poles of authenticity and audacity as to arrange them once more in some deliciously precarious balance – the way that the lonesome hobos of “Derelict” and “Ramshackle” haunted the stoned soul picnic of Odelay. Stephen Troussé

The LA maverick invokes Anglophile folk on first new album in six years…

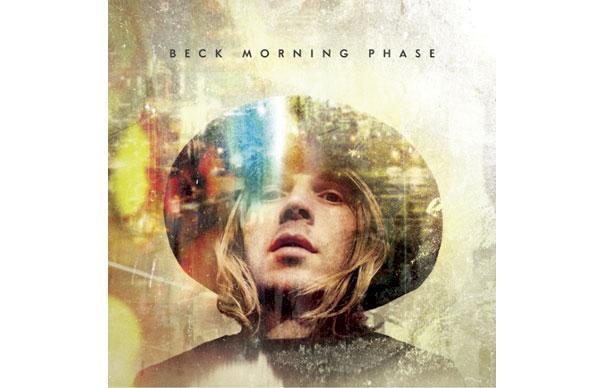

“Turn, turn away/From the sound of your own voice,” sings Beck towards the end of Morning Phase, his first new album in six years. Those lines serve as a pretty neat summary of his working methods during his hiatus, where he seemed to explore every possible musical avenue other than write and record an album of his own songs.

First he took a back seat as producer for fellow travellers such as Thurston Moore and Stephen Malkmus, most strikingly and successfully crafting and co-writing Charlotte Gainsbourg’s IRM. Then there was the enjoyably ramshackle Record Club, where he assembled disparate like-minds – Liars, St Vincent, Devendra Bernhardt, Feist, members of Tortoise, Wilco and Os Mutantes – to record a version of a favourite album – The Velvet Underground & Nico, INXS’s Kick – in one day.

Most satisfying – conceptually, artistically and in performance – there was 2012’s Song Reader: an album in the form of sheet music, a tribute to the lost American songbook from before recording, which culminated in a delirious, unhinged performance at the Barbican featuring interpretations from Jarvis Cocker, Franz Ferdinand and The Mighty Boosh. If the gap years were a deliberate attempt to recharge the batteries and to revive his muse, then by the climax of the Barbican show – leading his raggle-taggle troupe in a raucous singalong – he seemed a man revived.

Right enough last year, unexpected one-off singles appeared – “Gimme”, “I Won’t Be Long” and best of all, the Animal Collective-ish “Defriended”. If Record Club seemed to gently establish him as a godfather of 21st-Century blog-rock, then every sign seemed to be that he was gradually re-emerging to reclaim his crown. Morning Phase isn’t quite such a bold return. Rather than lighting out for new territory or reaffirming his place as high-concept freakfolk/artpop conjuror, the new record returns to the Beck of Sea Change, the plangent, acoustic, confessional album he recorded in 2002 in the wake of his break-up with long-term girlfriend Leigh Limon. Though Beck himself seems reluctant to consider Morning Phase a companion piece or twisted sibling to the earlier recording, it does reassemble the same group of musicans – guitarists Smokey Hormel and Jason Falkner, keyboard player Roger Manning and drummer Joey Waronker.

Morning Phase dawns with “Cycle”, an unsettling Arvo Part-y string drone – the first of a couple of orchestral interludes – before beginning in earnest with “Morning”. “Woke up this morning…” he keens – and here you might anticipate some lyrical dislocation, a monkey wrench in the genre mechanics but instead he continues faithfully, earnestly, “from a long night in the storm”.

Like Sea Change, Morning Phase seems intent on pursuing emotional authenticity deep into plain speaking, and even cliché. His research into sheet-music history of the American songbook may even have heightened this commitment: elsewhere on the new record you find another track titled “Blue Moon” without the faintest wink of irony.

Beck has talked about how he found inspiration for Morning Phase in the cosmic Caliornian music of his youth, the wild-honey harmonies of The Byrds and Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, and on “Morning” you hear a hint of the pie-eyed starsailing of Judee Sill. But elsewhere if you think of The Byrds you’re more likely to be put in mind of the desolate dawn chill of “Draft Morning”. The album is presented as a new dawn for Beck, but emotionally it feels still tied to the trauma that triggered Sea Change. After emerging from the storm, Beck continues, “Looked up this morning/Found the rose was full of thorns”.

Furthermore, rather than California dreams, Morning Phase generally evokes a more wintry, Anglophile folk music. “Heart Is A Drum” distills the soundworld of Nick Drake’s Bryter Layter – the frosty clarity of the acoustic fingerpicking, the tinkling brook of piano and looming Robert Kirby orchestral cloudscape, here reprised by Beck’s father, David Campbell. “Turn Away” owes something to Simon & Garfunkel’s “The Sound Of Silence” while the closing “Waking Light” aspires to the interstellar bombast of Roger Waters’ Pink Floyd.

Individually there are some wonderful songs on Morning Phase. “Blackbird Chain” is a small marvel, shuffling through time signatures like prime Lee Hazlewood, Smokey Hormel’s mercurial guitar flowering and then spiralling across “Country Down” as Beck sings of “a tiger rose growing through your prison floor”.

But cumulatively Morning Phase can feel too consistent in mood and pace. The songs tread some well-worn melodic routes, and Beck’s thin but serviceable voice is dulled rather than bolstered when multitracked into harmony. “Unforgiven” distills some of the problems of the record. Over echo-laden electric piano chords Beck sings solemnly of driving into the night, into the afterglow, to somewhere unforgiven. In a way that seems somehow typical of Gen Xers (think of how Johnny Depp or Leo DiCaprio still seem boyish and unconvincing as leading men), Beck is unable to convincingly get into the saddle of this kind of mythic American deepsong – it feels forced and unconvincing, like someone trying to sing an octave too low.

One of the more intriguing songs is “Wave”. It’s just Beck alone on an orchestral seascape, like Robert Redford in “All Is Lost”, singing atonally of “isolation”. The song was originally written for Charlotte Gainsbourg and it hints tantalisingly at some fresh, strange, latter-day Scott Walker horizons for Beck. Along with the preceding singles, and the talk of a second album already in the works, it makes you wonder if Morning Phase was selected as simply the most commercially tenable release for Beck to return with – a placeholder rather than statement of ambition.

But this also highlights quandary that may have led to Beck’s six-year hiatus. Back in 2006, Uncut’s John Mulvey remarked on the irony that, for a supposed maverick, Beck had succumbed to routine: “He releases a hip-hop/pop/blues romp showcasing his post-modern hipster schtick. Then he follows it up with a faintly ethereal, largely straight-faced singer-songwriter album, helmed by Nigel Godrich.” As impressive as Morning Phase in places is, it doesn’t disturb this formula – even if it’s followed up by a wilder, stranger album. This division may make the records easier to market but it hobbles Beck’s antic muse. If the second act of his career is to be as arresting as the first, his problem is not so much to synthesise the poles of authenticity and audacity as to arrange them once more in some deliciously precarious balance – the way that the lonesome hobos of “Derelict” and “Ramshackle” haunted the stoned soul picnic of Odelay.

Stephen Troussé