There’s a touching moment in Becoming Led Zeppelin when Robert Plant is played a tape of a previously lost interview with his old friend John Bonham. Bonzo is talking with huge fondness about his bandmates and Plant’s weathered face breaks into a huge grin as he listens – later there’s a similar reaction from Jimmy Page and John Paul Jones.

All three living members of the band are interviewed in Bernard MacMahon’s long-awaited documentary of Zep’s early years, but there’s something very moving about the footage of Bonham, which was recorded close to the point of impact rather than with the benefit of 50 years’ hindsight.

As Bonham relates his affection for his bandmates, it’s a reminder that everything we know about Zeppelin – the hardness of their music, image, management, approach to outsiders, attitude towards partying – might not be the full story.

MacMahon is a Londoner who made his breakthrough with the American Epic series that explored the roots of US music – folk, blues and country, but also Hawaiian, Cajun, Mexican-American and Native American. He has been working on Becoming Led Zeppelin since at least 2020, with an early cut screened at the Venice Film Festival in 2021. It’s worth the wait.

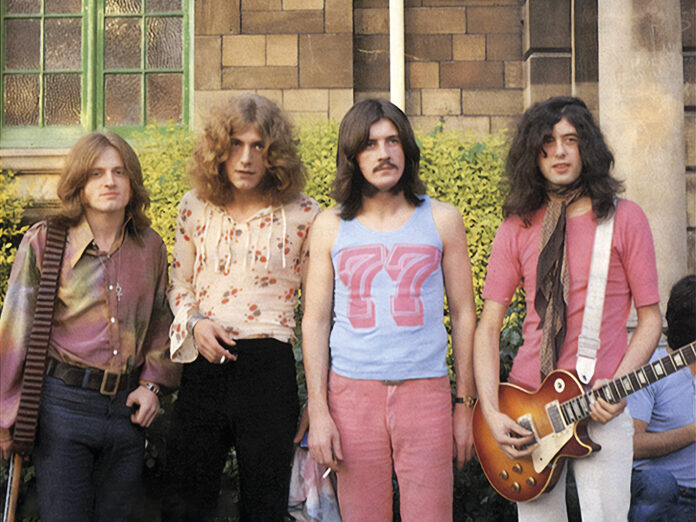

The first half of the film sees the four band members take it in turns to relate their individual journeys through the musical landscape of post-war Britain to the rehearsal room at 39 Gerrard Street, where Plant, Page, Jones and Bonham first played together on “Train Kept A-Rolling”. This includes great footage of Page and Jones as serious London session men, which contrasts neatly with Plant and Bonham’s earthier experiences on the Midlands rock circuit. The second half traces the quartet’s thrilling ascent towards world domination, originally as the New Yardbirds and then as Led Zeppelin.

That there are no interviewees other than Page, Plant and Jones – plus that old tape of Bonham – demonstrates MacMahon’s confidence in his core material. He doesn’t need Zeppelin’s contemporaries to provide context, or the rock stars of today to explain why Zeppelin mattered: the band can do it for themselves. The three rich and detailed interviews with Plant, Page and Jones are supplemented with archive radio and TV interviews, including hilarious radio interviews with Plant and adoring female fans.

Each band member seems to be given equal time to tell their story, bringing a welcome balance to the narrative. It’s the same balance that Page says he wanted to bring to the music, with every element of the quartet as important as another.

But the heart of the film comes from incredible live performance. There are clips from Fillmore West and college campuses, as well as larger festivals such as Atlanta Pop, Newport Jazz and Texas International Pop Festival. While much of the concert material comes from the many American tours of 1969, there’s also footage of Zeppelin at the 1969 Bath Blues Festival that causes Page to sit forward in amazement when it is played to him on a monitor – he says he’s seen photos, but this is the first time he’s seen film of the concert. One of the best moments comes from a French TV broadcast in 1969, where the audience cover their ears in horror as Zeppelin unleash rock Armageddon in the form of “Communication Breakdown”.

As MacMahon diligently tracks Zeppelin going back and forward between America and Europe throughout 1969, there’s a feeling that he doesn’t quite know how to end things. Zeppelin are on the ascendency – too good to cut away from – but their foundational story is clearly complete. He closes the film with coverage of the band’s triumphant homecoming at the Royal Albert Hall in January 1970. It’s a finale begging for a sequel.