Does Mick Ronson need critical rehabilitation? The contention of this slick, single-issue documentary is that down-to-earth, unassuming Ronno never received his due, and that his contribution to Bowie’s rise and rise has languished – in the words of the film’s PR messaging – “virtually unc...

Does Mick Ronson need critical rehabilitation? The contention of this slick, single-issue documentary is that down-to-earth, unassuming Ronno never received his due, and that his contribution to Bowie’s rise and rise has languished – in the words of the film’s PR messaging – “virtually uncelebrated”. Sure, he was a genius guitarist, but that’s underselling matters. Mick Ronson should instead be viewed as David Bowie’s multi-skilled creative director, the man who designed and built Ziggy’s architecture, transformed Lou Reed’s Transformer, and alchemised his boss’ impossible vision into rock’n’roll gold. And all for £50 a week.

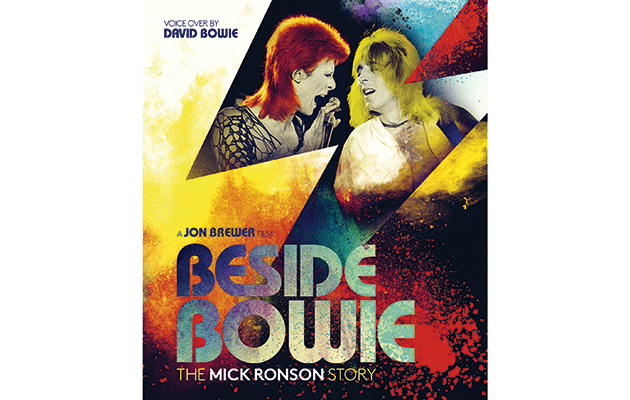

The case is presented skilfully by music industry insider/film director Jon Brewer, who worked with the Bowie camp in the ’70s (alongside 10 Years After, Gene Clark, Yes and Gerry Rafferty) and is the man behind multiple rock docs, including the Classic Artists Series, and an acclaimed life of BB King. His little black book has been thumbed extensively for this 102-minute essay, which features new interviews with Tony Visconti, Angie Bowie, Ian Hunter, Rick Wakeman, Earl Slick, Mick’s wife Suzi and sister Maggi, Dana Gillespie, Def Leppard’s Joe Elliott and more. It’s blue chip, certainly: there’s an eerie, oddly stilted voiceover from Bowie, interviews with Lou Reed, and archive chats with Ronno himself.

Told in an uncomplicated chronological arc, the film traces Mick’s first encounters with Bowie, via mutual acquaintance, Rats/Hype drummer John Cambridge. There’s insiderist analysis into their John Peel session, with less than two hours rehearsal, when Bowie hires a clearly nonplussed Mick live on air. There are sweet moments, too, from future wife Suzi Ronson – who cut David’s mum’s hair in a Beckenham salon – and crashing out at the crumbling Bowie HQ, Haddon Hall. Ronson’s uncomplicated Hullishness is highlighted throughout. “I’d never seen rooms that big before,” recalls Ronson, in an archive spot. We hear about the night Mick partied at Andy Warhol’s apartment, enjoying a surprisingly traditional spread of “wine, cheese and crackers”. We step aboard the frighteningly fast Bowie fame train, from the world première of Hunky Dory at Friars, in Aylesbury (entrance: 50p), to Top Of The Pops, a chaotic US tour and Hammersmith’s ‘last show we’ll ever do’ shenanigans. The best sections here are those that take you inside the circus of ’72-’74, and articulate more fully the film’s central assertion. Tour manager Tony Zanetta is brilliantly candid on the insanity of Bowie’s first steps Stateside. Pianist Mike Garson – whose plangent, jazzist keys brought a new palette to the Bowie sound – offers the musician’s perspective, and privileges Ronson’s contribution over Bowie’s. “Who was the guy with the headphones, giving me the chord charts and telling me ‘That’s a B-Minor?’ That was Ronno.” In a nice touch, Garson performs an improvised solo tribute to Ronson, which soundtracks the film credits.

Visconti, too, is a great inclusion: 40 years on, he’s still almost incredulous at Ronson’s musicality, workrate and technical capabilities. It was Visconti who taught the guitarist the rudiments of scoring and orchestration, and within weeks Ronson was creating the sweeping, multi-tonal opulence that would characterise “Moonage Daydream” et al. Wakeman takes you inside the chord arrangements of “Life On Mars”, and Lou Reed, in the studio, pulls down the faders so Ronson’s baroque string arrangements can be heard in isolation. “Boy, Ronson is good,” he remarks, in some awe.

Money – or lack of it – is a recurring theme here. With Bowie in thrall to hardball manager Tony Defries (not interviewed here, unsurprisingly) and his MainMan machine, we are told how Mick and his fellow Spiders were essentially accused of treason for asking for more cash – and this despite the fact that Garson and other touring musicians were on a significantly better weekly wage.

Recognising Ronson’s huge value, Defries tried to set him up as a solo artist. But Mick was the lieutenant, not the general, and by this time, we’re an hour and 10 minutes in. Slaughter On 10th Avenue and Mick’s other solo output – and his on-off work with Mott The Hoople – is dealt with in perfunctory haste. Money colours this section too. His post-Bowie income was erratic, unpredictable and often negligible; the cash from Ronson’s producer role on Morrissey’s Your Arsenal in 1992 was spent first on the heating bill. The film is bookended by his contribution to the Freddie Mercury Tribute Concert, Ronno back onstage with Bowie, a last hurrah before his death from liver cancer in 1993, aged just 46.

Beside Bowie is intriguing rather than revelatory, thought-provoking rather than endlessly fascinating. It keeps its electric eye unwaveringly on that central message – and somehow without making Bowie out to be the bad guy.