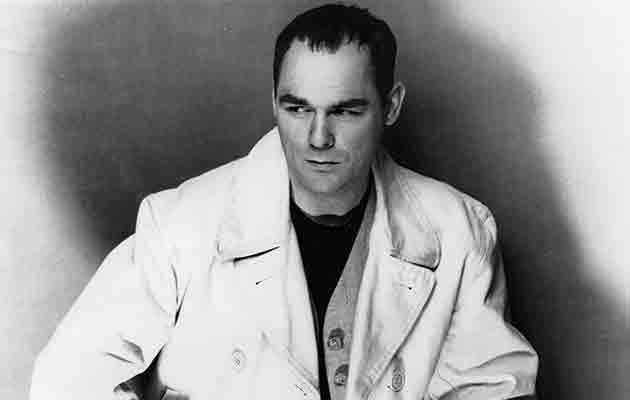

There are many stories, some funnier than others, about how unmanageable Billy MacKenzie was. The Rolls-Royce that he couldn’t drive; the hotel room for his whippets. Each absurd extravagance contributes to a picture of the singer as a quixotic, uncontrollable character with a consistent disregard for convention. That, of course, was his approach to music, and when working with Alan Rankine in The Associates, those impulses were mirrored in tunes which stretched pop into extraordinary shapes. Things were less satisfactory after MacKenzie and Rankine parted company in 1982. The singer’s subsequent career was an erratic collection of missed opportunities, some prompted by record companies unsure how to coax the best from a singer for whom retreat was the best form of attack.

It remains a cruel irony, then, that MacKenzie’s most coherent solo work, Beyond The Sun, was completed posthumously, following his suicide in January 1997. The record had a troubled genesis, and arguments remain about who did what, but it remains an elegant, powerful work, which balances MacKenzie’s easy command of the heartbroken ballad and his need to experiment. There is a sense of gloom, never more than on the title track, with its funereal piano, and a whispered vocal in which the singer gazes into a glorious, impossible future.

MacKenzie’s impetuosity was non-negotiable. He was grieving for his mother, and simultaneously imagining three albums – electronic, rock and (the one his new label Nude favoured) an acoustic album, with the singer framed as a more impish Scott Walker. He lost interest before the album was finished, and it was constructed from demos made with pianist Steve Aungle, and produced by Simon Raymonde, of Cocteau Twins, and Pascal Gabriel. MacKenzie’s exploratory urges are restricted to “3 Gypsies In A Restaurant” (programmed by John Vick of Finitribe) and the cascading “Sour Jewel”.

The finished work is perhaps closer to the record company’s wishes than MacKenzie’s more manic imaginings. But that’s no bad thing. It inhabits a contradiction, being mournful and resilient, lyrically oblique and emotionally translucent. “Give Me Time” (a co-write with Paul Haig) has a pulsing, European feel, “Winter Academy” is a beautifully icy ballad, its effect underlined by the pained ballad “Blue It Is”. Tempting as it is to view it in the context of MacKenzie’s suicide, the most moving song on the record, “And This She Knows”, was inspired, apparently, by a dream MacKenzie had about Kylie Minogue. And yet it is a haunting, fragile song, in which the melodrama of Aungle’s piano is harangued by Malcolm Ross’ distant guitar. Perhaps the choir which ushers the album to a close on “Nocturne VII” is too straightforwardly celestial, but it underlines the sense of loss which pervades this chilly, defiant album.