You might imagine that by now the history of cinema would be a written book, done and dusted. But there seem to be endless directors from the past left to be discovered - or, if they’ve had the misfortune to be forgotten, rediscovered. One such is Glauber Rocha, a pioneer of the Cinema Novo movement that galvanised Brazilian cinema in the 1960s. In Brazil, Glauber Rocha is anything but forgotten: there the Bahia-born director, who died in 1981 aged 43, is still revered and widely-screened, and his 1964 film Black God White Devil has been voted the greatest Brazilian film of all time. Outside Brazil, though, Glauber Rocha’s name has been largely neglected, his films generally associated with the wave of radicalism and sometimes visionary cinematic practice that emerged from Third World cinema in the 60s. But watch Black God White Devil today for the first time, and you’re in a shock - and you understand why Luis Buñuel, no less, declared the film “the most beautiful thing I have seen in a decade, filled with a savage poetry.” Black God is a startling piece of work, and savage indeed: it’s part Biblical myth, part epic ballad, part political drama, part Latin American Western. It’s also a great figures-in-a-landscape film, to equal those of another great 60s filmmaker currently being rediscovered, Hungary’s Miklos Jansco. Black God White Devil is set in the 1940s, although the feeling of timelessness is such that the action could easily be taking place in some pre-Columbian era, or in Old Testament times. The film’s anti-hero is Manuel (Geraldo del Rey), a poor farmer in the sertao, the arid plains of Brazil’s Northeast. Inspired by a vision of St George, Manuel strikes down an exploitative boss, then heads out across the plains, accompanied by his sceptical wife Rosa (Yona Magalhaes). In the film’s first hour, Manuel attaches himself to the peasant army following Sebastiao (Lidio Silva), a charismatic preacher of decidedly apocalyptic tendencies. Then, after an extremely brutal explosion of ritualistic violence of which they are the only survivors, Manuel and Rosa join the camp of Captain Corisco (Othon Bastos), a demented, demonic freebooter with a split personality, who rechristens Manuel ‘Satan’. The film’s second hour becomes a bizarre, haunting piece of Absurdist theatre, with the sertao’s sun-baked expanses as a stage. Hovering in the background of all this is the legendary hired killer Antonio das Mortes (Mauricio do Valle), a rifle-toting figure in a vast black hat and huge overcoat, who could have walked straight out of a Sergio Leone western - no coincidence, since Leone was a huge admirer of Rocha, and incorporated elements of his imagery into his own Man With No Name cycle. Shot by Waldemar Lima in stark black and white, the film certainly has the epic desolation of a Leone western, underwritten by a Marxist view of historical and political conflict that is straight out of the Eisenstein book. The film feels at once like a sprawling, spasmodically bloody nightmare, and like an allegory, with Manuel and Rose standing for the Brazilian people caught between the twin temptations of the Church and the Army. The cactus-studded sertao itself - disturbingly claustrophobic, for all its spaciousness - becomes as resonantly mythical a location as John Ford’s Monument Valley, while the scenes early on, as Sebastiao’s followers crowd around their idol on top of a mountain, has the exalted intensity of a Cecil B. de Mille Biblical drama, shot on a Poverty Row budget. Poverty is the word, in fact: in 1965, Glauber Rocha composed a manifesto proclaiming his “Aesthetic of Hunger”, and calling for a revolutionary cinema to express the rage of the dispossessed: he called his work, “these sad and ugly films, these desperate films where reason doesn’t always possess the loudest voice.” Black God White Devil certainly vaults way beyond reason, with the multiple-voiced Captain Corisco - bandit, clown, Napoleon figure - proving one of the most unsettlingly excessive figures in film. The film contains a pure streak of the Theatre of Cruelty prophecied by French writer Antonin Artaud, the Sebastiao story coming to a head with an exceptionally unnerving child sacrifice. The same spirit of Artaudian extremity would later inspire Latin American film visionaries such as Alejandro Jodorowsky, a more mystical and surrealistic kindred spirit to Glauber Rocha. The twin registers of the epic and the intimate are underpinned by Glauber Rocha’s use of contrasting musics: on one hand, a rudimentary narration provided by Sergio Ricardo’s folk balladry, on the other, the sweeping, sometimes bombastic orchestrations of the great Brazilian classical composer Heitor Villa-Lobos. Before his untimely death, Glauber Rocha went on to complete a trilogy, the other episodes being Terra em Transe and Antonio das Mortes, as well as other films including the wonderfully-titled study of African politics, Der Leone Have Sept Cabezas (1970). But he made Black God White Devil at the remarkable age of 25, and while the film is full of youthful fury, it also embodies a cinematic confidence and complexity beyond the director’s years. It is visionary cinema at its rawest. EXTRAS: None. JONATHAN ROMNEY

You might imagine that by now the history of cinema would be a written book, done and dusted. But there seem to be endless directors from the past left to be discovered – or, if they’ve had the misfortune to be forgotten, rediscovered. One such is Glauber Rocha, a pioneer of the Cinema Novo movement that galvanised Brazilian cinema in the 1960s. In Brazil, Glauber Rocha is anything but forgotten: there the Bahia-born director, who died in 1981 aged 43, is still revered and widely-screened, and his 1964 film Black God White Devil has been voted the greatest Brazilian film of all time. Outside Brazil, though, Glauber Rocha’s name has been largely neglected, his films generally associated with the wave of radicalism and sometimes visionary cinematic practice that emerged from Third World cinema in the 60s.

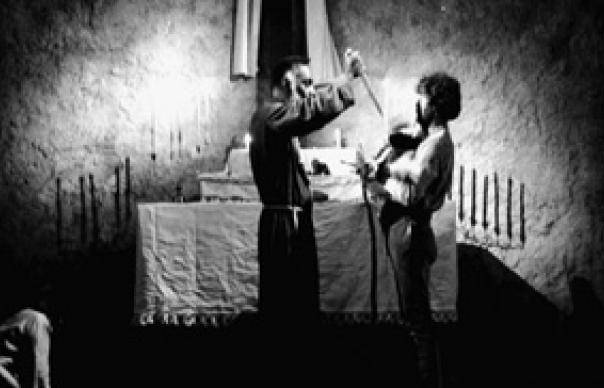

But watch Black God White Devil today for the first time, and you’re in a shock – and you understand why Luis Buñuel, no less, declared the film “the most beautiful thing I have seen in a decade, filled with a savage poetry.” Black God is a startling piece of work, and savage indeed: it’s part Biblical myth, part epic ballad, part political drama, part Latin American Western. It’s also a great figures-in-a-landscape film, to equal those of another great 60s filmmaker currently being rediscovered, Hungary’s Miklos Jansco.

Black God White Devil is set in the 1940s, although the feeling of timelessness is such that the action could easily be taking place in some pre-Columbian era, or in Old Testament times. The film’s anti-hero is Manuel (Geraldo del Rey), a poor farmer in the sertao, the arid plains of Brazil’s Northeast. Inspired by a vision of St George, Manuel strikes down an exploitative boss, then heads out across the plains, accompanied by his sceptical wife Rosa (Yona Magalhaes). In the film’s first hour, Manuel attaches himself to the peasant army following Sebastiao (Lidio Silva), a charismatic preacher of decidedly apocalyptic tendencies.

Then, after an extremely brutal explosion of ritualistic violence of which they are the only survivors, Manuel and Rosa join the camp of Captain Corisco (Othon Bastos), a demented, demonic freebooter with a split personality, who rechristens Manuel ‘Satan’. The film’s second hour becomes a bizarre, haunting piece of Absurdist theatre, with the sertao’s sun-baked expanses as a stage. Hovering in the background of all this is the legendary hired killer Antonio das Mortes (Mauricio do Valle), a rifle-toting figure in a vast black hat and huge overcoat, who could have walked straight out of a Sergio Leone western – no coincidence, since Leone was a huge admirer of Rocha, and incorporated elements of his imagery into his own Man With No Name cycle.

Shot by Waldemar Lima in stark black and white, the film certainly has the epic desolation of a Leone western, underwritten by a Marxist view of historical and political conflict that is straight out of the Eisenstein book. The film feels at once like a sprawling, spasmodically bloody nightmare, and like an allegory, with Manuel and Rose standing for the Brazilian people caught between the twin temptations of the Church and the Army. The cactus-studded sertao itself – disturbingly claustrophobic, for all its spaciousness – becomes as resonantly mythical a location as John Ford’s Monument Valley, while the scenes early on, as Sebastiao’s followers crowd around their idol on top of a mountain, has the exalted intensity of a Cecil B. de Mille Biblical drama, shot on a Poverty Row budget.

Poverty is the word, in fact: in 1965, Glauber Rocha composed a manifesto proclaiming his “Aesthetic of Hunger”, and calling for a revolutionary cinema to express the rage of the dispossessed: he called his work, “these sad and ugly films, these desperate films where reason doesn’t always possess the loudest voice.” Black God White Devil certainly vaults way beyond reason, with the multiple-voiced Captain Corisco – bandit, clown, Napoleon figure – proving one of the most unsettlingly excessive figures in film. The film contains a pure streak of the Theatre of Cruelty prophecied by French writer Antonin Artaud, the Sebastiao story coming to a head with an exceptionally unnerving child sacrifice. The same spirit of Artaudian extremity would later inspire Latin American film visionaries such as Alejandro Jodorowsky, a more mystical and surrealistic kindred spirit to Glauber Rocha.

The twin registers of the epic and the intimate are underpinned by Glauber Rocha’s use of contrasting musics: on one hand, a rudimentary narration provided by Sergio Ricardo’s folk balladry, on the other, the sweeping, sometimes bombastic orchestrations of the great Brazilian classical composer Heitor Villa-Lobos. Before his untimely death, Glauber Rocha went on to complete a trilogy, the other episodes being Terra em Transe and Antonio das Mortes, as well as other films including the wonderfully-titled study of African politics, Der Leone Have Sept Cabezas (1970). But he made Black God White Devil at the remarkable age of 25, and while the film is full of youthful fury, it also embodies a cinematic confidence and complexity beyond the director’s years. It is visionary cinema at its rawest.

EXTRAS: None.

JONATHAN ROMNEY