An LA country-folk masterpiece from 1974, unearthed... If Silent Passage had come out as originally planned in 1974, beardy Americana types might even now be touring a live version of it, much like Robin Pecknold and others have recently been performing Gene Clark’s No Other, an album it much resembles. Warner Bros actually had copies pressed and ready for distribution when a contractual stand-off between Carpenter and producer Brian Ahern saw the album’s release first postponed and eventually cancelled - introspective singer-songwriters no longer so much in vogue by the time the disputed contract had expired. Apart from a limited 1984 release on the small Canadian independent label Stony Plains Records, Silent Passage has therefore not been widely heard in 40 years, Carpenter subsequently pretty much giving up on music, devoting his life to religious studies and becoming ordained as a Buddhist monk even as he was dying in 1995 from inoperable brain cancer. Who was Bob Carpenter? According to a brief 1977 biography, he was part-Ojibway, born into the First Nations tribe at the Temagami Reservation in Northern Ontario and from a young age brought up in foster homes and orphanages, grim circumstances he escaped by joining the navy. Some years of vagabond itinerancy followed, Carpenter eventually in the mid-60s fetching up in Toronto, where he was inspired by Neil Young, Joni Mitchell and Gordon Lightfoot, regulars then in the city’s Yorkville folk clubs. During a hostile winter spent alone in a ramshackle log cabin on a remote British Columbia commune, he started writing the unique songs that brought him to the attention of Neil Young producer David Briggs, with whom he began an album for Capitol, soon abandoned after the pair fell out. This was a hint perhaps of difficulties to come when he was signed by Brian Ahern, a young Canadian producer who’d recently launched Anne Murray’s solo career, although he may be even better-known to Uncut readers as producer of Emmylou Harris, who appears here as backing vocalist on several tracks. Ahern took Carpenter to LA, where he’d assembled a crack band to back him that included LA session veterans Lee Sklar on bass and Russ Kunkel on drums, with Little Feat’s Lowell George and Bill Payne on guitar and keyboards, with further appearances from Ben Keith and Buddy Cage on pedal steel. Carpenter later complained Ahern gussied up too many tracks with unwelcome strings, woodwind, horns and backing singers. He would perhaps have preferred a starker sound, the better to accommodate the wounded intimacy of his songs, which were much preoccupied with a prevailing disillusion, not uncommon as the halcyon utopianism of the 60s gave way to the violent inclemency of the 70s (Carpenter’s big on unsettled weather as a metaphor for universal turbulence). To an extent, Silent Passage is a requiem for an era of betrayed promise, hence the grieving tone it shares with No Other and also After The Gold Rush, Jackson Browne’s Late For The Sky, Joni Mitchell’s Blue and Paul Siebel’s Jack-Knife Gypsy, all of them glum reflections on the hippie Diaspora of the era. This was after all a time of break up and disintegration. What had become known as the counterculture was fragmenting, its chastened membership variously embracing desperate hedonism (the “acid, booze and ass/needles, guns and grass” of Joni’s “Blue”), religion and terrorism. As many of the songs on Silent Passage recognise – conspicuously the handsome title track and “Morning Train” - at least until the fog lifted you were now pretty much out in the darkness on your own. The album opens almost jauntily with “Miracle Man”, a country rock gem in any circumstances, something of The Band’s rustic funkiness further enhanced by the bittersweet sting of a typically elegant Lowell George slide guitar solo. Carpenter’s voice, however, a grainy rasp occasionally reminiscent of Richie Havens, inclines more to the desolate woe and fretful uncertainty that consumes the bulk of the record, notably the brooding remorse of “Down Along The Borderline” and “Before My Time”, the eerie visions of “Gypsy Boy” and “First Light”, a dramatic anticipation of approaching apocalypse, the rapture to come, which on the closing “Now And Then” is embraced with startling fatalism. Allan Jones

An LA country-folk masterpiece from 1974, unearthed…

If Silent Passage had come out as originally planned in 1974, beardy Americana types might even now be touring a live version of it, much like Robin Pecknold and others have recently been performing Gene Clark’s No Other, an album it much resembles. Warner Bros actually had copies pressed and ready for distribution when a contractual stand-off between Carpenter and producer Brian Ahern saw the album’s release first postponed and eventually cancelled – introspective singer-songwriters no longer so much in vogue by the time the disputed contract had expired. Apart from a limited 1984 release on the small Canadian independent label Stony Plains Records, Silent Passage has therefore not been widely heard in 40 years, Carpenter subsequently pretty much giving up on music, devoting his life to religious studies and becoming ordained as a Buddhist monk even as he was dying in 1995 from inoperable brain cancer.

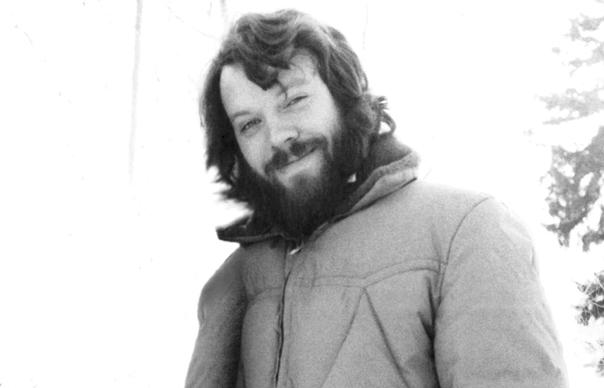

Who was Bob Carpenter? According to a brief 1977 biography, he was part-Ojibway, born into the First Nations tribe at the Temagami Reservation in Northern Ontario and from a young age brought up in foster homes and orphanages, grim circumstances he escaped by joining the navy. Some years of vagabond itinerancy followed, Carpenter eventually in the mid-60s fetching up in Toronto, where he was inspired by Neil Young, Joni Mitchell and Gordon Lightfoot, regulars then in the city’s Yorkville folk clubs. During a hostile winter spent alone in a ramshackle log cabin on a remote British Columbia commune, he started writing the unique songs that brought him to the attention of Neil Young producer David Briggs, with whom he began an album for Capitol, soon abandoned after the pair fell out. This was a hint perhaps of difficulties to come when he was signed by Brian Ahern, a young Canadian producer who’d recently launched Anne Murray’s solo career, although he may be even better-known to Uncut readers as producer of Emmylou Harris, who appears here as backing vocalist on several tracks.

Ahern took Carpenter to LA, where he’d assembled a crack band to back him that included LA session veterans Lee Sklar on bass and Russ Kunkel on drums, with Little Feat’s Lowell George and Bill Payne on guitar and keyboards, with further appearances from Ben Keith and Buddy Cage on pedal steel. Carpenter later complained Ahern gussied up too many tracks with unwelcome strings, woodwind, horns and backing singers. He would perhaps have preferred a starker sound, the better to accommodate the wounded intimacy of his songs, which were much preoccupied with a prevailing disillusion, not uncommon as the halcyon utopianism of the 60s gave way to the violent inclemency of the 70s (Carpenter’s big on unsettled weather as a metaphor for universal turbulence).

To an extent, Silent Passage is a requiem for an era of betrayed promise, hence the grieving tone it shares with No Other and also After The Gold Rush, Jackson Browne’s Late For The Sky, Joni Mitchell’s Blue and Paul Siebel’s Jack-Knife Gypsy, all of them glum reflections on the hippie Diaspora of the era. This was after all a time of break up and disintegration. What had become known as the counterculture was fragmenting, its chastened membership variously embracing desperate hedonism (the “acid, booze and ass/needles, guns and grass” of Joni’s “Blue”), religion and terrorism. As many of the songs on Silent Passage recognise – conspicuously the handsome title track and “Morning Train” – at least until the fog lifted you were now pretty much out in the darkness on your own.

The album opens almost jauntily with “Miracle Man”, a country rock gem in any circumstances, something of The Band’s rustic funkiness further enhanced by the bittersweet sting of a typically elegant Lowell George slide guitar solo. Carpenter’s voice, however, a grainy rasp occasionally reminiscent of Richie Havens, inclines more to the desolate woe and fretful uncertainty that consumes the bulk of the record, notably the brooding remorse of “Down Along The Borderline” and “Before My Time”, the eerie visions of “Gypsy Boy” and “First Light”, a dramatic anticipation of approaching apocalypse, the rapture to come, which on the closing “Now And Then” is embraced with startling fatalism.

Allan Jones