Every album, and a little bit more. Something is happening… In his new book, Yeah Yeah Yeah: The Story Of Modern Pop, Bob Stanley, with typical elegance and erudition, comes as close as any – actually, closer than most – to bottling the appeal of Dylan in the 1960s, when he owned good parts of the world and in return, the world followed his every move, pounced on every gnomic statement, and devoured every single and album like missives of unearthly wisdom. “Dylan was closed, entirely self-sufficient,” he writes. “He was his own planet and, naturally, you desperately wanted to find a way to travel there.” It seems oddly telling that Stanley’s book and this definitively not-quite-definitive set of all Dylan’s studio and live albums should appear on the shelves at roughly the same time. One celebrates the multiple narratives of pop pre-internet age, the religion of sharing records, taping music, following the charts, mapping the highways and by-ways of modern pop in all its manifold contradictions. Complete Album Collection Vol. One feels like a veiled attempt to wrap up a messy era and claim it as one’s own; to reduce all of that wild complexity to a series of totemic documents, albums plotted chronologically, with thoroughly decent and highly normative logic, and an extra double-disc compilation, entitled Sidetracks, which pulls together all the stray songs and b-sides that appeared on Dylan’s multiple compilation albums. So far, so Fred Fact. It’s hard to find fault with good portions of the music on these discs. By its very design, this box includes several albums that have taken the fabric of popular music and sheared it into new, unexpected styles: Bringing It All Back Home; Highway 61 Revisited; Blonde On Blonde; The Basement Tapes; Blood On The Tracks, you know the drill… Breathtaking moments of sublimity originally etched into twelve-inch grooves and subsequently reduced to twelve-or-so centimeters of digitalia for your continual consumption. Spend as much time as you need, want, desire with these albums: they’re hard to beat. Having Dylan’s fourty-one albums handed to you in one box also helps contextualize the many swerves and swoops in his career, both gracious and ungracious. There’s the post-Blonde run of cryptic, ghostly song forms on John Wesley Harding, Nashville Skyline, New Morning and Pat Garrett & Billy The Kid, a run that’s still pregnant with untapped possibility. There are the divisive albums of fierce, declamatory, conservative Christianity from the early ‘80s (hearing them together in one sitting is seriously draining, kinda like walking into a new school and being hazed by the entire student populace, but it’s almost worth it to be reminded of the brilliance of the furious, unrelenting “Jokerman”). There’s Oh Mercy, whose songs I still can’t entirely parse from the cotton wool blur that is Daniel Lanois’ production (the finest moment from these sessions, “Series Of Dreams”, is on The Bootleg Series Vol. 3, naturlich). There are also those two early ‘90s albums of folk songs, Good As I Been To You and World Gone Wrong, which felt weird at the time and have lost none of their puzzle quotient, for this listener at least, in the intervening years. Dylan never fully seized the moment after these albums, and a lot of what happened since – even acclaimed albums like “Love And Theft” or Tempest – have, well, felt like good-to-occasionally-great late-era Dylan records that wouldn’t get that much of a pass if they’d been attributed to a lesser icon. And that’s the story Complete Album Collection Vol. One fills out, ultimately: an incredibly sustained marathon of creativity across the ‘60s and ‘70s, some weird detours in the ‘80s, settling into ornery elder statesman/figurehead status from the ‘90s onward. In its way it presents a far more rounded and realistic picture of Dylan the songwriter than the more hallucinatory, hagiographic texts that have been written about him. It also reads a little like another in a long line of music industry tactics to meet or beat the ‘entire catalogue in 20 minutes’ download rhetoric of the torrent-scape: feel the width, friends. (Oh, and it’s also available as a ‘harmonica shaped USB’: how cute.) Ultimately, I’m left thinking, No more! Give these albums their rightful place in the firmament (or elsewhere), by all means, but dig further into those archives, please: dust off the Complete Basement Tapes; let Blood On The Acetates out of its box; bake those reels and let’s get serious with the hardcore shit. If you’re going to play to that collector crowd, the least you could do is sing their song, right? “Bob Dylan’s back catalogue is like a library,” Stanley continues, “with narrow, twisting corridors and deep oak shelves drawing you in: start leafing through the pages and you may never want to stop.” This box, conversely, is the Encyclopedia of Dylan. A monumental set of music, it’ll get you up to speed real quick, but it’s never going to replace the experience of happily stumbling from album to album, finding them in second-hand record bins, borrowing them from friends, and piecing together the myth from fragments of maps and legends. Dylan, the ultimate mystique artist? Maybe no more. Jon Dale

Every album, and a little bit more. Something is happening…

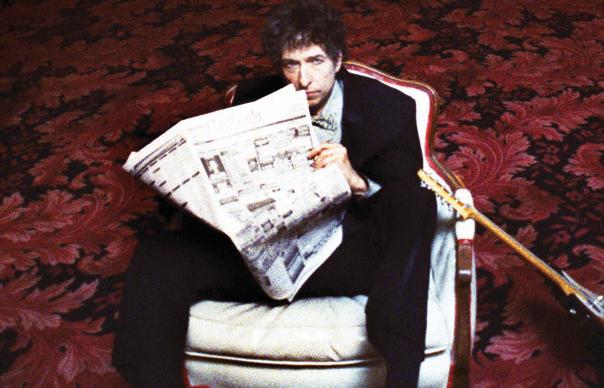

In his new book, Yeah Yeah Yeah: The Story Of Modern Pop, Bob Stanley, with typical elegance and erudition, comes as close as any – actually, closer than most – to bottling the appeal of Dylan in the 1960s, when he owned good parts of the world and in return, the world followed his every move, pounced on every gnomic statement, and devoured every single and album like missives of unearthly wisdom. “Dylan was closed, entirely self-sufficient,” he writes. “He was his own planet and, naturally, you desperately wanted to find a way to travel there.”

It seems oddly telling that Stanley’s book and this definitively not-quite-definitive set of all Dylan’s studio and live albums should appear on the shelves at roughly the same time. One celebrates the multiple narratives of pop pre-internet age, the religion of sharing records, taping music, following the charts, mapping the highways and by-ways of modern pop in all its manifold contradictions. Complete Album Collection Vol. One feels like a veiled attempt to wrap up a messy era and claim it as one’s own; to reduce all of that wild complexity to a series of totemic documents, albums plotted chronologically, with thoroughly decent and highly normative logic, and an extra double-disc compilation, entitled Sidetracks, which pulls together all the stray songs and b-sides that appeared on Dylan’s multiple compilation albums. So far, so Fred Fact.

It’s hard to find fault with good portions of the music on these discs. By its very design, this box includes several albums that have taken the fabric of popular music and sheared it into new, unexpected styles: Bringing It All Back Home; Highway 61 Revisited; Blonde On Blonde; The Basement Tapes; Blood On The Tracks, you know the drill… Breathtaking moments of sublimity originally etched into twelve-inch grooves and subsequently reduced to twelve-or-so centimeters of digitalia for your continual consumption. Spend as much time as you need, want, desire with these albums: they’re hard to beat.

Having Dylan’s fourty-one albums handed to you in one box also helps contextualize the many swerves and swoops in his career, both gracious and ungracious. There’s the post-Blonde run of cryptic, ghostly song forms on John Wesley Harding, Nashville Skyline, New Morning and Pat Garrett & Billy The Kid, a run that’s still pregnant with untapped possibility. There are the divisive albums of fierce, declamatory, conservative Christianity from the early ‘80s (hearing them together in one sitting is seriously draining, kinda like walking into a new school and being hazed by the entire student populace, but it’s almost worth it to be reminded of the brilliance of the furious, unrelenting “Jokerman”). There’s Oh Mercy, whose songs I still can’t entirely parse from the cotton wool blur that is Daniel Lanois’ production (the finest moment from these sessions, “Series Of Dreams”, is on The Bootleg Series Vol. 3, naturlich).

There are also those two early ‘90s albums of folk songs, Good As I Been To You and World Gone Wrong, which felt weird at the time and have lost none of their puzzle quotient, for this listener at least, in the intervening years. Dylan never fully seized the moment after these albums, and a lot of what happened since – even acclaimed albums like “Love And Theft” or Tempest – have, well, felt like good-to-occasionally-great late-era Dylan records that wouldn’t get that much of a pass if they’d been attributed to a lesser icon.

And that’s the story Complete Album Collection Vol. One fills out, ultimately: an incredibly sustained marathon of creativity across the ‘60s and ‘70s, some weird detours in the ‘80s, settling into ornery elder statesman/figurehead status from the ‘90s onward. In its way it presents a far more rounded and realistic picture of Dylan the songwriter than the more hallucinatory, hagiographic texts that have been written about him. It also reads a little like another in a long line of music industry tactics to meet or beat the ‘entire catalogue in 20 minutes’ download rhetoric of the torrent-scape: feel the width, friends. (Oh, and it’s also available as a ‘harmonica shaped USB’: how cute.)

Ultimately, I’m left thinking, No more! Give these albums their rightful place in the firmament (or elsewhere), by all means, but dig further into those archives, please: dust off the Complete Basement Tapes; let Blood On The Acetates out of its box; bake those reels and let’s get serious with the hardcore shit. If you’re going to play to that collector crowd, the least you could do is sing their song, right?

“Bob Dylan’s back catalogue is like a library,” Stanley continues, “with narrow, twisting corridors and deep oak shelves drawing you in: start leafing through the pages and you may never want to stop.” This box, conversely, is the Encyclopedia of Dylan. A monumental set of music, it’ll get you up to speed real quick, but it’s never going to replace the experience of happily stumbling from album to album, finding them in second-hand record bins, borrowing them from friends, and piecing together the myth from fragments of maps and legends. Dylan, the ultimate mystique artist? Maybe no more.

Jon Dale