Only God knows who’s responsible for Bob Dylan’s conversion to Christianity. He had already been touring most of the year when he rolled into San Diego in November 1978, physically and creatively weary from the road. Toward the end of the show, an unidentified fan lobbed a small silver cross onstage. Dylan picked up and kept it, even wearing it around his neck at later shows. In December, he debuted two new songs with overtly Christian lyrics and claims to have been visited by Jesus Christ.

Soon Dylan converted to a particularly evangelical strain of Christianity, even engaging in an intense three-month course at the Association of Vineyard Churches. Over the next three years he transformed his concerts into tent revivals and churned out three gospel-rock records. He cast himself as a fire-and-brimstone preacher cheering the glory of God and warning of His almighty wrath. It’s not just one of the weirder chapters of his career, but one of the most unexpected plot twists in rock history.

Forty years later it’s been written so deeply into the narrative of his career that it seems like a momentary distraction in retrospect, a waystation on a longer spiritual quest, a new guise adopted by a mercurial artist. And it’s such a short era as well. In fact, by Dylan’s fascination with Sinatra has dwarfed his Christian output in both duration and output. With each year and each new album it becomes more and more difficult to reconstruct this moment, when fans and critics alike wondered if Dylan was actually serious and how long it would last. That makes Dylan’s Christian period more fitting—not less—for an entry in his remarkable Bootleg series. If there’s any phase that need a hearty defense and demands explication, it’s the late 1970s.

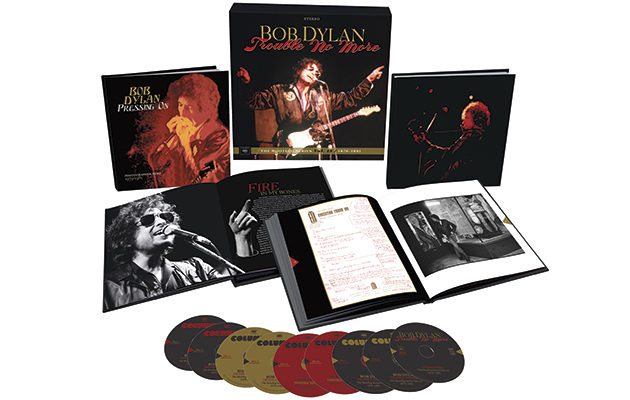

One of the most exhaustive installments in the series—100 previously unreleased live and studio cuts gathered on 9 CDs, plus a DVD featuring a feature-length film — Trouble No More does a fine job with the task, arguing with varying degrees of persuasiveness that the era wasn’t entirely a wash. It was, though, a low point for his songwriting. Gone are the tangles of metaphor and allusion, the haunted American backdrop, the thickly veiled social and political commentary, and the ambiguity that compelled his listeners to engage actively with his songs. Suddenly, Dylan was suddenly writing with emphatic, disconcerting certainty. Slow Train Coming, released in 1978, remains his most compelling testament from the era, with “Gotta Serve Somebody” generally considered a greatest hit. But apart from “Every Grain of Sand”, 1979’s Saved and 1980’s Shot of Love remain the province of only the most committed fan.

Trouble No More is not apologetic about or embarrassed by Dylan’s conversion. Rather, these outtakes and live cuts show just how thoroughly he had committed himself to his newfound faith and just how fundamental a change it exerted on his craft. If his studio albums suffered, the songs found new life and purpose onstage, and Dylan sounds like Lazarus on “Solid Rock” and “Ain’t Gonna Go To Hell From Anybody”. The live version of “I Believe In You” from 1980 features a surprisingly soulful vocal, as he conveys not only the hardship but the joy in belief. His backup singers are a near-constant presence on these songs, almost as prominent as the man himself—and for good reason: Dylan dated two of them and married the third a few years later.

What truly saves these songs, however, is Dylan’s band, which includes guitarist Fred Tackett, keyboard player Spooner Oldham, drummer Jim Keltner, and occasionally Mark Knopfler. They turn these songs into elastic rock jams, turning “Slow Train Coming” inside out and injecting some fervor and fury into “Dead Man Dead Man.” Dylan cut almost all of his old material from his set, but he still cautioned his generation about letting the counterculture curdle into complacency, especially on a fiery “When You Gonna Wake Up.” On the rare occasion when he did revisit older songs, they sound wholly different in this new context. It’s especially bracing to hear this band rip through a triumphal version of “Blowin’ in the Wind” that might have more to say about God than any of his overtly Christian songs.

Dylan’s Christian phase seemed to end as abruptly as it began. His attention turned to the Kabbalah, and 1983’s Infidels addressed that subject, albeit more obliquely. It’s tempting to dismiss this chapter in Dylan’s career as something akin to a temporary illness, although it might be more accurate to think of it as a temporary fix to a different illness. Trouble No More presents a very humane portrait of a man on a serious spiritual quest, which makes it as biographically fascinating as it is musically frustrating.