By the spring of 1978 Bob Marley was ready for a new challenge. His media status as ‘The First Third World Superstar’ was attested by soaring global record sales. That he had ended 15 months of exile from Jamaica following the attempt on his life – returning to play the ‘Peace Concert’ tha...

By the spring of 1978 Bob Marley was ready for a new challenge. His media status as ‘The First Third World Superstar’ was attested by soaring global record sales. That he had ended 15 months of exile from Jamaica following the attempt on his life – returning to play the ‘Peace Concert’ that brought a truce to Kingston’s bullet-prone streets – also marked a turning point. He’d done his bit for his country. What was next?

Marley’s answer was to undertake the biggest tour of his career, one that renewed his wooing of the all-important North American market and which would take him to Milwaukee, Maryland and Montreal as well as the already conquered capitals of the East and West coasts. Also in his sights were Japan, Australia and, of course, Africa. All would fall to Trenchtown’s conquering lion and his strange music – strange because for most of the world roots reggae was still an odd, scarcely heard quantity.

But first we take Manhattan…and Boston, a city that had always been kind to the Wailers, and whose Music Hall hosted two shows (early and late) on June 8, the former supplying this live album, the fifth in Marley’s canon after Live! (cut 1975), Babylon By Bus (cut 1977), and the posthumous Live At The Roxy (cut 1976) and Live Forever (his last performance, cut 1980).

Unusually, Marley had personally allowed dispensation to a young fan to film the show from the front row. The resulting footage is an engaging addition, though better concert film is already freely available (the Boston stadium show of 1979 for example).

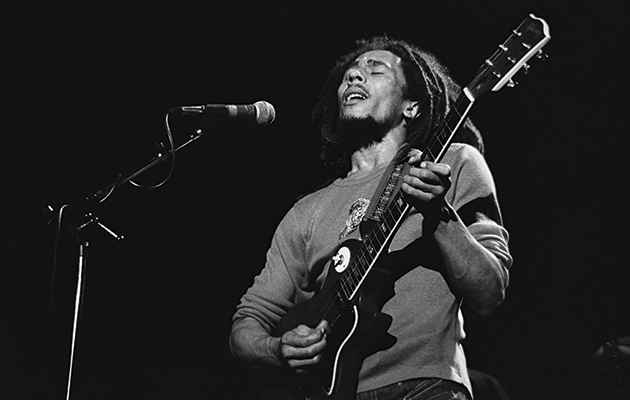

It proves a sweet enough set, entirely typical of the well-drilled band Marley oversaw in his pomp (and make no mistake, Bob ruled over his group with an iron hand). The rhythm section of the Barrett brothers had always synchronised effortlessly, Family Man’s loping bass lines weaving around Carly’s snapping rim shots. The duo were the lynchpin around which the Wailers turned – for much of this set Tyrone Downie’s keyboards and the guitars of Junior Marvin and Al Anderson do little more than punctuate their rhythms, at last in this somewhat muddy sound mix. Most of the musical action is otherwise contained by Marley’s vocals – always committed and rarely less than extraordinary, even in the midst of a gruelling tour – and the under-valued choral counterpoints of the I Three, a trio more distinguished than the usual ‘backing vocals’ description suggests, and whose discipline allows Marley to improvise and wander.

Though this was the ‘Kaya Tour’ – said album had been released in March – the only track from that record is “Easy Skanking”, which drifts past unremarkably. Kaya was a kick-back album. In concert, something tougher was called for, and Marley invariably relied on a mix of militant anthems and greatest hits – the opening quartet of “Slave Driver”, “Burning’ and Lootin’”, “Them Belly Full” and “Heathen” is a salvo of anger and defiance, after which comes a clutch of lighter crowd-pleasers; “Rebel Music”, “I Shot The Sheriff”, “No Woman No Cry” and “Lively Up Yourself”, a number that featured in almost every show Marley and his band played.

By 1978 other constants had emerged. “War”, containing the words of Hailie Selassie, was like scripture for Marley, and he and the band had cleverly segued it into “No More Trouble”, thus balancing the songs’ messages. “Lively Up Yourself”, a number that had started life as languid rock steady back in the Bob/Bunny/Tosh era, had evolved into a high-spirited celebration of livity. “Get Up Stand Up” (co-written with Peter Tosh let’s not forget) was another ever-present, a catchy singalong on one level that was also combative and Rastafarian in outlook.

As the show proceeds, the numbers grow longer, partly to allow Marley to do more dancing and gesticulating, but also to let the twin guitar attack of Anderson and Marvin more space. Their squealing blues-rock guitars had always been a bone of contention among reggae fans, with accusations of ‘sell-out’ not uncommon. The squalls of guitar over the last 30 minutes of this show certainly have their tedious moments. The reality was that Marley was engaged in the reinvention of reggae, and just as black American acts like Funkadelic had adopted rock elements, so had he. Transforming the Wailers from a studio-stuck vocal trio into a fully functioning band had itself been a revolutionary act; turning Jamaican music into something less alien to a global audience was, for Marley, a continuation of the same process.

His real aim, one that would never be fulfilled in his lifetime, was to engage and revolutionise black America, to fulfil the prophecy of “Exodus”. That number ends Easy Skanking in a thunder of double beats that the sound quality here turns into an uninteresting thump. It isn’t really reggae at all, but it is uniquely Bob Marley.