As the ’80s dawned, humanity was once again turning its eyes to the skies. In March 1983, Ronald Reagan, a former screen cowboy turned 40th President Of The United States, unveiled his latest strategy in an increasingly hot Cold War – a strategic missile defence system which, in a nod to the pop culture of the day, earned the nickname “Star Wars”. Star Wars was conceived in the very American spirit that the best defence was a good offence.

The idea was that a notional Soviet strike might be averted by simply blasting enemy missiles out of the sky with laser-guided warheads – a sort of nuclear-powered equivalent of the quick-witted gunslinger in a Hollywood western who disarms his opponent by shooting the revolver out of his hand. It was all a reminder that the cosmos represented something new in the American psyche: not merely a blank canvas to be explored, but a place to be conquered – in the words of another TV show, the final frontier.

Order the latest issue of Uncut online and have it sent to your home!

Some four months after Reagan’s speech, music fans were granted another, rather more benign vision of the cosmos. Brian Eno had been experimenting with his idea of ambient music for approaching a decade, but Apollo: Atmospheres & Soundtracks was perhaps the finest, most refined example of ambient to date. Apollo is mostly rooted in a sort of dreamy somnambulance, but in fact underwent a rather troubled birth. It was originally commissioned as the score to a feature-length documentary by director Al Reinert that made use of previously unseen 35mm footage of the Apollo 11 moon landings. But after some poorly received test screenings, Reinert returned to the editing suite for some extensive reworking. (The film finally saw wide release in 1989 under the name For All Mankind, with some of Eno’s score excised.)

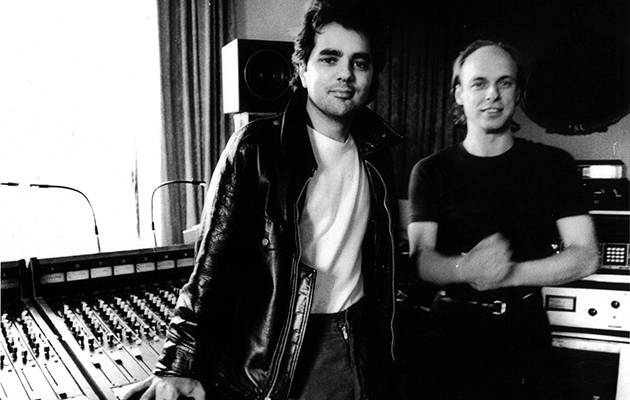

Instead, Eno’s Apollo took on a life of its own. In places, its 12 tracks recall earlier records that sought to grapple with the majesty and enormity of the cosmos. “The Secret Place” and “Signals” owe something to the minimal kosmische music practised by German electronic groups like Tangerine Dream and Cluster, creating a lonely and isolated sound using heavily treated guitars and synths soaked in echo and delay. But Apollo is not all so abstract. On the contrary, the presence of two new collaborators – a young Canadian guitarist/producer named Daniel Lanois and Eno’s younger brother Roger, a classically trained pianist here making his recording debut – nudges Apollo into more overtly musical territory.

Speaking with Reinert, Eno had discovered that all the astronauts on the Apollo mission had been allowed to take a cassette into space, and all but one had taken country music. Eno had grown up on country, which he had heard on American Armed Forces radio as a child, and he was struck by the juxtaposition. Country music, he told an interviewer in 1990, was “very much like ‘space music’… it has all the connotations of pioneering, of the American myth of the brave individual, and that myth has strong resonances throughout American culture.” In a way, then, Apollo is a sort of space-age frontier music. Tracks like “Silver Morning” and “Deep Blue Day” envisage a sort of weightless country & western, the soundtrack to an eternity drifting across the great plains of space, propelled by Lanois’ languid pedal steel.

This re-release commemorates 50 years since the Apollo 11 moon landings. While such anniversary events typically prompt a dredging through the archive for diverting outtakes, here Eno has taken a different approach. Alongside the original LP, remastered in full by Abbey Road’s Miles Showell, Eno reconvened the original trio for the first time since 1983, to create 11 brand-new tracks reimagining the soundtrack to For All Mankind. Unlike the original sessions, the trio worked remotely, with Lanois in the US and Roger Eno in Suffolk. The MIDI or WAV files they produced were then sent over to the elder Eno’s London studio, where he assembled the finished article. “What you hear now is a collaboration distant both in geographical terms, from one another, and temporal terms, from the original project,” explains Roger Eno.

Much of the spirit of the original remains intact though, but, with the division of labour split among more democratic lines, it’s perhaps easier to determine individual contributions. You can see Brian Eno’s fingerprints all over the eerie music-box progressions of “At The Foot Of The Ladder”, but a handful of Lanois compositions foreground chiming acoustic guitar and lap steel, radiating a sense of deep calm. And there is no doubting the quiet power of Roger Eno’s contributions; his “Waking Up” is striking in its restraint, little starbursts of treated piano bordering on moments of silence that feel like a quick gulp of oxygen.

Opening track “The End Of A Thin Chord” recalls Apollo’s “Deep Blue Day”, a sort of interstellar exotica spun from gentle, chiming melodies and a slight dusting of distortion, while Roger Eno’s chilling “Under The Moon” is bleaker in sound than anything on the original LP. Perhaps the most moving piece, though, is Brian Eno’s “Clear Desert Night”, with its lonely stargazing feel.

It’s an odd sort of idea: a trio paying tribute to themselves. But even if no new ground is being broken exactly, there’s a pleasure in hearing the old space cadets out on manoeuvres. The music of Apollo is meditative and benign, yet strangely inscrutable; a reminder that while you might be able to visit space, it will never be home.