Brian Eno’s last two albums – 2006’s Another Day On Earth and 2008’s Everything That Happens Will Happen Today, the latter recorded with David Byrne – have seen him return to The Song. While warmly received in some quarters, there remain some of us who don’t really like Eno’s “proper songs” or his rather affected voice, and prefer it when he’s doing what he does best – making spookily beautiful ambient instrumentals. Small Craft On A Milk Sea sees Eno revert to what he’s spent most of the last three decades doing, providing soundtracks for imaginary films. He has found an appropriate home for it on the Warp label, home of like-minded sonic explorers such as Aphex Twin, Broadcast, Battles and Boards Of Canada. But where Eno’s previous ambient music – using generative computer software, tape loops, phase systems and so on – saw him working solo from purely electronic sources, this project sees him collaborating with “proper musicians”. Eno subjects them to some of the methods he’s used in the past as a producer of David Bowie, Talking Heads, Coldplay and U2 (game theory, Oblique Strategy cards, getting them to swap instruments), all the time deploying the “direct inject anti-jazz raygun” method that he once used with Robert Wyatt (manipulating the sounds with effects and digital delay units). His accomplices here are two multi-instrumentalists, Jon Hopkins and Leo Abrahams, both contributors to previous Eno projects. Both are seasoned session men – Abrahams is a multi-instrumentalist, songwriter and arranger who appears to be the first port of call for numerous pop stars (including Carl Barât, Brett Anderson, Ed Harcourt and Paloma Faith) who require someone to flesh out their unfinished ideas. For more than a decade, Abrahams and Hopkins have played completely improvised gigs – you can sometimes see them in small venues, going on stage without any pre-prepared ideas and performing hypnotic, drone laden instrumental jams. This project sees Eno putting a peculiarly Eno-esque twist to such improvisations. He gets them to play freely, puts effects on their instruments, joins in on the keyboards and then goes through the recordings to isolate the most interesting passages. You can hear how songs like “Complex Heaven” or “Horse” – based around drones, repetitive basslines, simple guitar riffs and slowly mutating melodies – were created in this way. Some of the more interesting compositions employ even weirder working methods. Eno would write down a series of chords on a whiteboard and then point randomly at one, getting Hopkins and Abrahams to improvise on that chord before pointing randomly at another chord and then another, not knowing whether or not the ensuing sequence of chords would work together or not. It’s the kind of sky-blue thinking that only a “non-musician” like Eno would ever come up with, and the approach works dividends on tracks such as “Emerald And Lime” and “Emerald And Stone”, both compelling modern classical miniatures allied to lovely melodies. All this makes the album sound like an arid conservatoire experiment, but it’s more than that. Many of its tracks, like the Morricone-feeling “Written, Forgotten”, are designed to drift into the background – upmarket mood music, if you will – but others demand your attention. The proggy trip hop of “Bone Jump”, the drum’n’bass chase sequence of “Flint March”, the frankly terrifying “Forms Of Anger” – all rumbling bass, tribal percussion and spooky guitar effects – will leap out of the speakers. Interestingly, the final track, “Late Anthropocene”, sees Eno, Abrahams and Hopkins improvising together and producing the kind of floaty soundscapes that resemble something produced on Eno’s specially designed pieces of generative music software. To get humans to recreate some of the world’s most complicated computer programmes must, in Eno’s world, presumably rank as a triumph. John Lewis Q+A I came across a comment on a blog saying “Brian Eno signing to Warp is like if Miles Davis had signed to ECM”… Yeah. Well that’s quite encouraging. Home at last! It’s surprisingly noisy in places... Oh good! Well I’m a big Battles fan as you may know, I really like them a lot. And I’m actually a big Warp fan. I like the spectrum they represent and where that particular spectrum is. What particular qualities do Jon Hopkins and Leo Abrahams have as musicians which made you want to work with them? They are both very interested in sonic worlds. This is an argument I always have with classically trained people. Because they just do not get that this is the major difference between pop music and what they do. The major difference isn’t that we syncopate rhythms or play instruments. The major difference is that we work with sound as our material. Not with melody or rhythm or lyrics. But with sound. This is why you can have thousands of records with essentially the same chords, which all sound different... INTERVIEW: STEPHEN TROUSSÉ

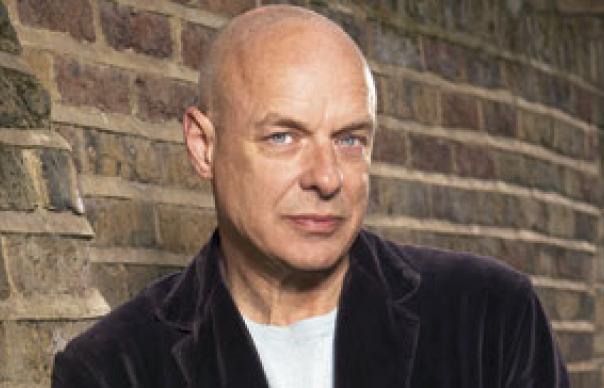

Brian Eno’s last two albums – 2006’s Another Day On Earth and 2008’s Everything That Happens Will Happen Today, the latter recorded with David Byrne – have seen him return to The Song. While warmly received in some quarters, there remain some of us who don’t really like Eno’s “proper songs” or his rather affected voice, and prefer it when he’s doing what he does best – making spookily beautiful ambient instrumentals.

Small Craft On A Milk Sea sees Eno revert to what he’s spent most of the last three decades doing, providing soundtracks for imaginary films. He has found an appropriate home for it on the Warp label, home of like-minded sonic explorers such as Aphex Twin, Broadcast, Battles and Boards Of Canada. But where Eno’s previous ambient music – using generative computer software, tape loops, phase systems and so on – saw him working solo from purely electronic sources, this project sees him collaborating with “proper musicians”. Eno subjects them to some of the methods he’s used in the past as a producer of David Bowie, Talking Heads, Coldplay and U2 (game theory, Oblique Strategy cards, getting them to swap instruments), all the time deploying the “direct inject anti-jazz raygun” method that he once used with Robert Wyatt (manipulating the sounds with effects and digital delay units).

His accomplices here are two multi-instrumentalists, Jon Hopkins and Leo Abrahams, both contributors to previous Eno projects. Both are seasoned session men – Abrahams is a multi-instrumentalist, songwriter and arranger who appears to be the first port of call for numerous pop stars (including Carl Barât, Brett Anderson, Ed Harcourt and Paloma Faith) who require someone to flesh out their unfinished ideas.

For more than a decade, Abrahams and Hopkins have played completely improvised gigs – you can sometimes see them in small venues, going on stage without any pre-prepared ideas and performing hypnotic, drone laden instrumental jams. This project sees Eno putting a peculiarly Eno-esque twist to such improvisations. He gets them to play freely, puts effects on their instruments, joins in on the keyboards and then goes through the recordings to isolate the most interesting passages. You can hear how songs like “Complex Heaven” or “Horse” – based around drones, repetitive basslines, simple guitar riffs and slowly mutating melodies – were created in this way.

Some of the more interesting compositions employ even weirder working methods. Eno would write down a series of chords on a whiteboard and then point randomly at one, getting Hopkins and Abrahams to improvise on that chord before pointing randomly at another chord and then another, not knowing whether or not the ensuing sequence of chords would work together or not. It’s the kind of sky-blue thinking that only a “non-musician” like Eno would ever come up with, and the approach works dividends on tracks such as “Emerald And Lime” and “Emerald And Stone”, both compelling modern classical miniatures allied to lovely melodies.

All this makes the album sound like an arid conservatoire experiment, but it’s more than that. Many of its tracks, like the Morricone-feeling “Written, Forgotten”, are designed to drift into the background – upmarket mood music, if you will – but others demand your attention. The proggy trip hop of “Bone Jump”, the drum’n’bass chase sequence of “Flint March”, the frankly terrifying “Forms Of Anger” – all rumbling bass, tribal percussion and spooky guitar effects – will leap out of the speakers.

Interestingly, the final track, “Late Anthropocene”, sees Eno, Abrahams and Hopkins improvising together and producing the kind of floaty soundscapes that resemble something produced on Eno’s specially designed pieces of generative music software. To get humans to recreate some of the world’s most complicated computer programmes must, in Eno’s world, presumably rank as a triumph.

John Lewis

Q+A

I came across a comment on a blog saying “Brian Eno signing to Warp is like if Miles Davis had signed to ECM”…

Yeah. Well that’s quite encouraging. Home at last!

It’s surprisingly noisy in places…

Oh good! Well I’m a big Battles fan as you may know, I really like them a lot. And I’m actually a big Warp fan. I like the spectrum they represent and where that particular spectrum is.

What particular qualities do Jon Hopkins and Leo Abrahams have as musicians which made you want to work with them?

They are both very interested in sonic worlds. This is an argument I always have with classically trained people. Because they just do not get that this is the major difference between pop music and what they do. The major difference isn’t that we syncopate rhythms or play instruments. The major difference is that we work with sound as our material. Not with melody or rhythm or lyrics. But with sound. This is why you can have thousands of records with essentially the same chords, which all sound different…

INTERVIEW: STEPHEN TROUSSÉ