For two decades, it’s been impossible to categorise French director Olivier Assayas. If there’s a British equivalent, it’s probably Michael Winterbottom. Themes, textures, moods and modes shift radically from movie to movie – sometimes, with Assayas, within a single movie. But underpinning everything is a restless fascination with what it means to be human, what it’s like to be in the world, and how the world is put together, at every level. Certainly, few who saw Assayas’ last film, Summer Hours, an intimate, deceptive family drama staring Juliette Binoche, will be expecting him to follow it up with this: a harsh, forensically detailed, epically dimensioned biopic of the international leftist terrorist known as Carlos The Jackal, which, in its violence and scope, its coldness and heat, plays like a cross between The Baader Meinhof Complex, Mesrine and GoodFellas. Made for French TV, Carlos is presented in two versions in this four-disc set. There’s the two-and-a-half hour theatrical cut, but the way to watch is to sink into the original three-part series, running over five hours. Covering 1973 – 1994, the year Carlos was captured and convicted, Assayas shows us a lot of the man born Ilich Ramirez Sánchez, but never really tries to explain him, or kid us that he can. An opening disclaimer makes clear the movie was based on rigorous research, but also that it must be taken as fiction. In a brilliant performance, Edgar Ramirez makes Carlos both charismatic and repellent. You never know him. You’re never sure if there’s anything worth knowing. First encountered as an operative for the Popular Front For The Liberation Of Palestine, preparing a bombing campaign in London, Assayas presents Carlos as fully formed. No backstory, no passages about his childhood in Venezuela. All his ideas and ideals are already fixed, and remain unchanging until the end. The question is, what are they? Is he, as his passionate, hectoring rhetoric insists, a true, committed revolutionary? Or a strutting mercenary thug, driven by ego? The character study boils down to two moments: the young Carlos, standing naked before a mirror, admiring his toned body; and the flabbier man of 20 years (and many radical chicks) later, refusing to accept he’s been discarded by history, checking into a clinic for liposuction on his love handles. Around this Assayas, hopping the globe from bloody episode to bloody episode with little pause for reflection, offers a concise history in how radical political violence played out across Europe during the final Cold War years. Often, it was as the most horrendous kind of black comedy. Many of the terrorist’s schemes are stumbling, bungled failures; a sequence depicting a militant gang’s plan to take a rocket launcher to an airport and blow up planes on the runway could fit into Chris Morris’ satirical comedy Four Lions. Each episode has its own internal rhythm, corresponding to where Carlos is in his career. The first, as he seeks to carve his reputation, is hectic, bitty. The second, as he hits full notoriety with the audacious 1975 raid on an OPEC conference in Vienna, is intensely thrilling. The final part, with Carlos a man without a country, washed up in Sudan following the collapse of the Berlin Wall and the shift in the geopolitical dynamic, is slow, fuzzy, burned-out, all talk. Through it all, Assayas manages to get up close and yet keep his distance, puncturing the narrative with odd fades to black and flashes of music (New Order, The Feelies, Wire, even The Dead Boys’ “Sonic Reducer”.) Carlos is a flawed, knotty piece, but knows it can’t be anything else. Its ambition knocks you sideways. And it could leave you depressed. In the UK, we’ve come to accept that the best American TV drama has far outstripped British television. Now it turns out French TV has left us standing, too. EXTRAS<.strong>: Making-of, interviews with Assayas and Ramirez. *** Damien Love

For two decades, it’s been impossible to categorise French director Olivier Assayas. If there’s a British equivalent, it’s probably Michael Winterbottom. Themes, textures, moods and modes shift radically from movie to movie – sometimes, with Assayas, within a single movie. But underpinning everything is a restless fascination with what it means to be human, what it’s like to be in the world, and how the world is put together, at every level.

Certainly, few who saw Assayas’ last film, Summer Hours, an intimate, deceptive family drama staring Juliette Binoche, will be expecting him to follow it up with this: a harsh, forensically detailed, epically dimensioned biopic of the international leftist terrorist known as Carlos The Jackal, which, in its violence and scope, its coldness and heat, plays like a cross between The Baader Meinhof Complex, Mesrine and GoodFellas.

Made for French TV, Carlos is presented in two versions in this four-disc set. There’s the two-and-a-half hour theatrical cut, but the way to watch is to sink into the original three-part series, running over five hours. Covering 1973 – 1994, the year Carlos was captured and convicted, Assayas shows us a lot of the man born Ilich Ramirez Sánchez, but never really tries to explain him, or kid us that he can. An opening disclaimer makes clear the movie was based on rigorous research, but also that it must be taken as fiction.

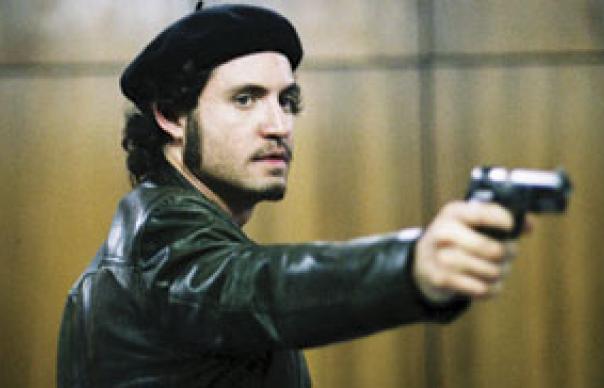

In a brilliant performance, Edgar Ramirez makes Carlos both charismatic and repellent. You never know him. You’re never sure if there’s anything worth knowing. First encountered as an operative for the Popular Front For The Liberation Of Palestine, preparing a bombing campaign in London, Assayas presents Carlos as fully formed. No backstory, no passages about his childhood in Venezuela. All his ideas and ideals are already fixed, and remain unchanging until the end.

The question is, what are they? Is he, as his passionate, hectoring rhetoric insists, a true, committed revolutionary? Or a strutting mercenary thug, driven by ego? The character study boils down to two moments: the young Carlos, standing naked before a mirror, admiring his toned body; and the flabbier man of 20 years (and many radical chicks) later, refusing to accept he’s been discarded by history, checking into a clinic for liposuction on his love handles.

Around this Assayas, hopping the globe from bloody episode to bloody episode with little pause for reflection, offers a concise history in how radical political violence played out across Europe during the final Cold War years. Often, it was as the most horrendous kind of black comedy. Many of the terrorist’s schemes are stumbling, bungled failures; a sequence depicting a militant gang’s plan to take a rocket launcher to an airport and blow up planes on the runway could fit into Chris Morris’ satirical comedy Four Lions.

Each episode has its own internal rhythm, corresponding to where Carlos is in his career. The first, as he seeks to carve his reputation, is hectic, bitty. The second, as he hits full notoriety with the audacious 1975 raid on an OPEC conference in Vienna, is intensely thrilling. The final part, with Carlos a man without a country, washed up in Sudan following the collapse of the Berlin Wall and the shift in the geopolitical dynamic, is slow, fuzzy, burned-out, all talk.

Through it all, Assayas manages to get up close and yet keep his distance, puncturing the narrative with odd fades to black and flashes of music (New Order, The Feelies, Wire, even The Dead Boys’ “Sonic Reducer”.) Carlos is a flawed, knotty piece, but knows it can’t be anything else. Its ambition knocks you sideways. And it could leave you depressed. In the UK, we’ve come to accept that the best American TV drama has far outstripped British television. Now it turns out French TV has left us standing, too.

EXTRAS<.strong>: Making-of, interviews with Assayas and Ramirez. ***

Damien Love