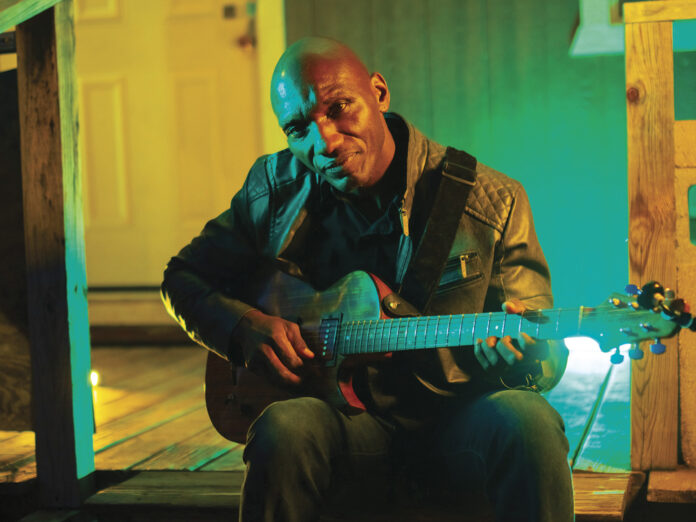

Almost halfway through Hill Country Love, Cedric Burnside untangles a skein of blues from his guitar and starts singing, “Here I go, bout to walk through the door/I see people, all over the floor/I can’t blame them, the music is hot you know.” The opening of “Juke Joint”, one of the many high points of Burnside’s new album, does much to position his songwriting, and his music, within the rich tradition of hill country blues, placing it firmly in the juke joint: old rural weekend venues where black communities would gather to drink, eat, hang out and play music. It’s no surprise, then, that photographer and scholar Bill Steber once called juke joints the “kiln where the musical fires burned brightest” in the Mississippi Delta.

Almost halfway through Hill Country Love, Cedric Burnside untangles a skein of blues from his guitar and starts singing, “Here I go, bout to walk through the door/I see people, all over the floor/I can’t blame them, the music is hot you know.” The opening of “Juke Joint”, one of the many high points of Burnside’s new album, does much to position his songwriting, and his music, within the rich tradition of hill country blues, placing it firmly in the juke joint: old rural weekend venues where black communities would gather to drink, eat, hang out and play music. It’s no surprise, then, that photographer and scholar Bill Steber once called juke joints the “kiln where the musical fires burned brightest” in the Mississippi Delta.

DAVID BOWIE IS ON THE COVER OF THE LATEST UNCUT – ORDER YOUR COPY HERE

For Burnside, the juke joint is emblematic of both the development of hill country blues, and the community spirit that informs his music. He’s particularly well placed to carry that history: his grandfather was legendary hill country blues musician, RL Burnside; his father, Calvin Jackson, was a drummer who played with the likes of Jessie Mae Hemphill and Junior Kimbrough. All were key players who brought hill country blues into the late 20th and early 21st century. Burnside started playing with his grandfather, who he calls Big Daddy, in his mid-teens; negotiating the road as a youngster opened his eyes, and when he’d return to school after touring, his fellow students would say he “talked like a fifty-year old”, Burnside laughs.

Being around such musicians also helped Burnside understand, at an almost molecular level, the histories of hill country blues, and the way those histories inform how this seemingly sui generis music comes together. Fundamentally, it builds out of fife and drum blues, a form of music where a cane fife (a small flute) player leads a troop of drummers. This music was first documented for a wider listenership by Alan Lomax, who ‘discovered’ Sid Hemphill, one of the key sources of hill country blues, in the early ’40s. From that music, and subsequent fife and drum corps like Othar ‘Otha’ Turner and his Rising Star Fife and Drum Band, you get the single-minded stream of melody and polyrhythmic complexity that makes Hill country blues so unique.

If anyone can be singled out as being responsible for bringing hill country blues to wider attention, though, it’s Mississippi Fred McDowell, whose Lomax recordings are among the foundational texts of modern blues. Burnside tips his hat to McDowell several times on Hill Country Love, giving remarkably faithful, spirited performances of McDowell classics “You Got To Move” and “Shake Em On Down”. On both, Burnside goes acoustic, the slide burring beautifully against the strings as Burnside sings these songs with deft confidence and a sensitivity to the curious corners of the melodies; he’s obviously drunk deeply from McDowell’s archive of recordings, and he knows how to mobilise that knowledge and understanding to stay faithful to the music’s past, while carving his own initials into the music too.

But the connection with McDowell, for Burnside, is even more intimate and immediate. “Him and my Big Daddy was really good friends,” he says. “They played house parties together; they drank moonshine together. He was one of the ones that I really wish I could have got to meet and shake his hand. That’s one of the reasons why I put ‘Shake Em On Down’ and ‘You Got To Move’ on the album. My Big Daddy used to play those songs.” One thing that keeps doubling back, throughout Hill Country Love, is the remarkably interwoven community that is hill country blues, the way the Burnside and Hemphill dynasties are so core to the music and its development, and the way this history feeds itself and creates parameters for the music that are, however, never limitations.

You can hear those connections and parameters most clearly, perhaps, in the closing “Po Black Maddie”, where Burnside takes on a song from his grandfather’s catalogue and makes it his own. It’s one of the album’s most bravura performances, the guitar playing limber and lithe as Burnside and his band ride the song’s mantric riff and structure to the skies. It’s also an excellent example of what makes this music so special and unique – it’s fixed to a point; the music is hypnotic, droney, repetitive, but not reductively so, and it creates its own energy, its own head of steam, through such stark repetition. “I think that’s one of the good things of hill country blues,” Burnside reflects, “that drone, that hypnotic beat. It’s always going. No matter where the music goes, that beat is still there.”

If there’s a key to Hill Country Love’s 14 songs, it’s perseverance, when it comes both to the music, and to the life that sustains it. On “I Know”, Burnside’s cat’s-claw guitar figure is shadowed, beautifully, by Patrick Williams’ harmonica, keening away in the back of the mix, before stepping forward for a solo that draws as much as it can out of a child’s clutch of notes. A run of songs midway through the album weave together tightly to create parallels between dedication to one’s faith, and dedication to one’s music: “Closer”’s clipped guitars are tracked by Burnside’s rich voice, while “Love You Music” is carried by a riff that’s strangely filigree, while drummer Artemas LeSueur, the understated heartbeat of Hill Country Love, shifts from deep, sly toms, to martial clamour on the snare.

“Toll On They Life” feels like the album’s centrepiece, though, the simple poetry of Burnside’s lyrics cracked open by a surprising, unexpected chord change that leads the song into new terrain, briefly: the flourish feels like light chiming through carriage doors. Throughout, Burnside is quietly observational, taking in the way “People get mad when things don’t quite go the way they want/They do crazy things out of spite”; soon he’s warning, “People will lie in your face/To get things to go they way.” What’s remarkable about Burnside’s delivery here is the way it see-saws between a kind of dispassionate observation and an understated, yet stern judgement – something he can flick between in the simple curve of a syllable.

Lest this all sounds too heavy, Burnside’s also able to cut loose, to follow a groove to its natural conclusion. “Funky” does just what it says, with a railway rhythm from LeSueur matched by a grinding guitar riff and Burnside’s itchy, tetchy repetition, like a dancefloor mantra, of the title’s imperative. “Smile” is slower, but the chipped guitar riff with its decisive cut-offs, traced in outline by sleepy harmonica and the deep prowl of the bass, has a sensuous, smoky sway. Luther Dickinson’s bass playing on the album can slip by at times, but it’s a keen, grounding weight to the songs, giving them real heft.

Dickinson’s also co-producer of the album, along with Burnside himself. Recorded in a rather prosaically described “old building in Ripley, Mississippi”, you get the sense here of two friends at play; this is music created with ease, songs that are uncluttered, with no fuss or flash, but plenty of commitment. It’s another compelling achievement for a blues artist whose institutional recognition – a Grammy for best traditional blues album for 2021’s I Be Trying; the Mississippi Governor’s Arts Award for Excellence – actually makes perfect sense. As the keeper of the flame of hill country blues, Burnside’s earned it, and then some.