The use of the definite article in the title is revealing. This is not just ‘a’ John Coltrane documentary, it is positioned as the authorised story of one of American music’s most enduring cultural icons, a questing, spiritual tenor saxophonist who, in his 40 short years, helped shape the course of jazz. A big claim, then. But anyone who has seen John Scheinfeld’s previous work (The US Vs John Lennon or Who Is Harry Nilsson (And Why Is Everybody Talkin’ About Him)?) will know the screenwriter/director adopts a forensic approach to filmmaking, and is capable of bringing zinging insight to even the most documented subjects.

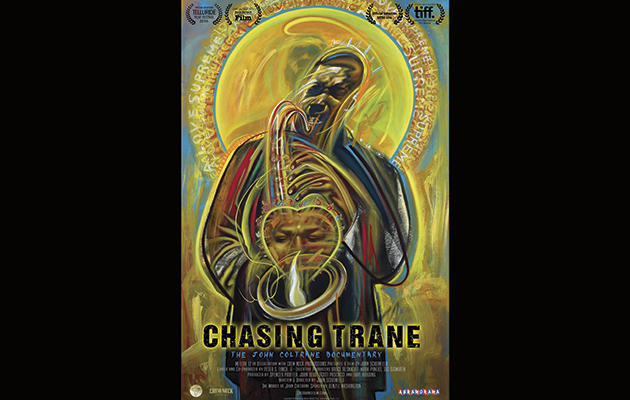

Chasing Trane is a heavyweight; the movie equivalent of a high-gloss, hardback coffee-table artbook. It is made with the full participation of the Coltrane family, including his stepdaughter (from first marriage to Naima Grubbs) and his children with Alice (née McLeod) Coltrane. Told entirely through new interviews, intercut with remarkable home cinefilm footage and animated photo-montages, it looks slick, plush, expensive. Coltrane’s own words are intoned by Denzel Washington, no less. The impeccably selected soundtrack is matched to beautiful, rhythmical artwork from Rudy Gutierrez, illustrator of a remarkable children’s book, Spirit Seeker: John Coltrane’s Musical Journey.

The interviewees, too, are excellent. In the I-was-there corner, jazz legends: Sonny Rollins, Wayne Shorter, Reggie Workman, Jimmy Heath and Benny Golson. In the ‘my hero’ camp: Carlos Santana, The Doors’ John Densmore, rapper Common, Wynton Marsalis – whose expert technical analysis of Coltrane’s musicality is superb – and the 42nd president of the United States, Bill Clinton. Assorted journalists, biographers and cultural commentators punctuate the anecdotes with unimprovised fact, and the whole product is rather gorgeous.

Chasing Trane has a conventional narrative. This is a chronological walk through Coltrane’s life, from his ministerial upbringing in North Carolina, through the devastating loss of his father and grandfathers as a child, to initial awkward musical fumblings as a “country bumpkin” in Philadelphia. As part of the US Navy corps, Coltrane was stationed at Pearl Harbour in ’45 and ’46, and it was here that he made his first recordings. These are roundly derided by the talking heads as “not representative”, and that’s probably the closest you get to criticism in the whole one-and-half hours of Chasing Trane, which, it must be said, can border on the hagiographic.

Coltrane is repeatedly portrayed as kind, thoughtful, even sweet; a musician who took some years to find himself and his sound. The film races through his apprenticeship in (in his words) “the minor leagues”, before big breaks with Dizzy Gillespie, and his first stint with Miles Davis (’55-’56). These should have been giant steps, but he was fired from both outfits for drug abuse. This is dealt with in hushed sympathy; his stepdaughter offers a moving account of how he quit heroin with no support, the coldest of cold turkey.

1957 saw his spiritual awakening, first work with the inspirational Thelonious Monk, and his first solo album for Prestige, Coltrane. He got back on “the high-diving board”, and rejoined Miles Davis – but now more confident, and self-aware. There’s an excellent dissection of his second stint with the Miles. Coltrane was recording Giant Steps between the Kind Of Blue sessions in spring ’59, and some brilliant archive footage shows an unfettered Trane soloing lengthily, while Miles steps offstage, to have a cigarette. We fast-forward to Coltrane’s later solo work, his radio hit with “My Favourite Things”, and then – Classic Album style – explore the adulation afforded on 1965’s A Love Supreme. Much of the fascinating latter part of the film is framed around his life with Alice, his peaceful politics, and his embrace of the avant-garde. The metaphor here is that new saxophone tone: the celestial, cathartic “shrieking” that divided critics and fans.

It’s unilaterally agreed here that his death in July 1967 robbed music of one its breathless innovators. “John was about the big picture,” says Sonny Rollins. “He had a deep feeling for higher worlds.” Praise for the spirituality and universality of his music comes from all quarters. Santana describes Coltrane as “the sound of light and the sound of love… a vortex of possibility”. Clinton offers similar praise. As a musician, Trane was “a master of his soul”.

There’s no doubt Chasing Trane is a brilliant primer, an elegant, effortless watch, and a superbly assembled piece of documentary. Is this the real man, though? Perhaps its very officialness robs it of journalistic impartiality; and too many rosy tints are superimposed on an already colourful life.