Around the time of the 2009 release of The Clientele’s Bonfires On The Heath, Alasdair MacLean described the imminent cessation of his band’s activities as more like a chapter’s close than a final page. Either way, it was quite an achievement for the story to last so long given The Clientele�...

Around the time of the 2009 release of The Clientele’s Bonfires On The Heath, Alasdair MacLean described the imminent cessation of his band’s activities as more like a chapter’s close than a final page. Either way, it was quite an achievement for the story to last so long given The Clientele’s happenstance existence. After evolving in fits and starts in London through the ’90s, the band only solidified into an ongoing concern when Merge released the early-works collection Suburban Light in 2000, thereby minting an American following that became surprisingly passionate for an act brandishing such thoroughly British reference points as the poetry of Ralph Hodgson. The influence of Surrealist art and literature provided a more continental air to the four exquisitely wrought studio albums that ensued, though MacLean maintained his favourite bands all hailed from LA, like Love and The Byrds.

By the end of the decade, MacLean was asking himself if The Clientele had anything left to say. As he said at the time, “You constantly have to rethink what you’re doing and wonder whether it’s courageous again.” After 2010 mini-album Minotaur, The Clientele did indeed close up shop, though even this hiatus didn’t much feel like one. It was more of a half-life, punctuated with the occasional gig, a generous campaign of reissues and the pair of lovely albums MacLean made with Pipas singer Lupe Núñez-Fernández, the duo recording and touring as Amor De Dias when not busy raising a family.

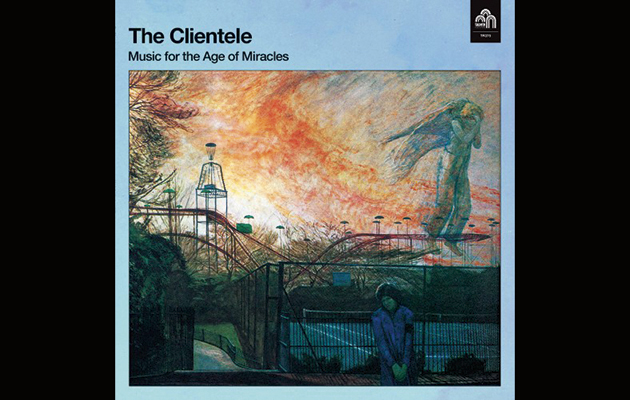

So perhaps it’s not surprising to have The Clientele back with its first collection of new music in seven years. What is startling is the abundance of new ideas and feeling of renewed vitality on Music For The Age Of Miracles, qualities that make the songs as compelling as any the band have recorded.

This process of rejuvenation began when MacLean had a chance encounter with Anthony Harmer, a friend and musician he hadn’t seen since the mid-’90s. In the years between their meetings, Harmer had mastered the santoor, a hammered dulcimer long favoured by Iranian and Indian classical musicians. Its bright, chiming sound became a key element in the music that emerged from their collaborations. These became fully fledged Clientele songs after MacLean brought bassist James Hornsey and drummer and pianist Mark Keen back into the fold.

At times, the santoor emphasises aspects that have long been part of The Clientele’s palette, the band’s sound having always nodded toward ’60s baroque-influenced pop without being unduly slavish about it. As before, there are echoes of The Hollies and The Zombies in songs like “The Neighbour”, the album’s beatific, harmony-laden opener. With its combination of the santoor’s harpsichord-like brightness and the opening phrase of “Ballerina, breathe”, “Everything You See Tonight Is Different From Itself” evokes The Left Banke’s “Pretty Ballerina”, an orch-pop touchstone if there ever was one.

But that’s certainly not the only colour here, nor the only texture. Instead, the songs on …Miracles can seem like so much Swiss clockwork, full of cycles within cycles and interconnected parts moving in tandem. Nowhere is that clearer than on “Falling Asleep”, which shifts from moments of squelchy radio noise, to sequences more evocative of the santoor’s Eastern roots, to sections of extraordinary intricacy and delicacy thanks to Harmer’s strings and brass arrangements. Here and elsewhere, MacLean’s warm, whispery vocals serve as the fixed point around which everything else revolves. Though The Clientele frontman has long expressed his love of Boards Of Canada, this is the closest his band has been to crafting a companion to The Campfire Headphase. There are further echoes of the Warp duo’s dense psych-folk masterpiece in the fine instrumental interludes by Keen, and other unexpected moments that recall the pastoral electronica of BOC peers Ultramarine.

The richness of the musical settings do not detract from MacLean’s skills as a lyricist. His songs make their own constant and subtle shifts from the prosaic – like the sounds of ordinary household commotion in “Falling Asleep”, the “thud of feet and muffled shutting doors” – to more cryptic mentions of “the year that the monster will come” in the haunting “Lunar Days”. Though always wary of nostalgia, he repeatedly returns to descriptions of moments that get swallowed up by memories too vivid to be pleasant. The most unnerving example arrives in “The Museum Of Fog”, a spoken-word piece in which the narrator visits a pub of his youth only to be overpowered by ghosts of his past and more sinister forces. Any band that has persisted as long as The Clientele may be similarly haunted by ghosts of younger selves. But reunions of much-cherished acts rarely yield new music that stakes such a strong claim to the present, a fact that makes Music For The Age Of Miracles its own kind of miracle.

Q&A

Alasdair MacLean

What inspired you to revive The Clientele?

In the early 2000s, I used to hear an old man play the Chinese dulcimer at one end of the Greenwich foot tunnel, on the way to work. I’d always been enchanted by the sound – like a carousel crossed with a music box crossed with a harpsichord – and always wanted to get it on a Clientele record. Then I bumped into Anthony Harmer on a street corner in Walthamstow in 2014 – the first time I’d seen him in 20 years. I’d often wondered what had happened to him. It turned out he’d studied the santoor, an Iranian version of the dulcimer, and over decades become a virtuoso, at least by my standards. He suggested we have a jam together. Ant and I now lived three streets away from each other – the coincidences were piling up.

The arrangements and orchestration are so rich and inventive on the album, too. Why did you feel like the new songs demanded this kind of scope and lushness?

What you’re hearing are the edited, minimalist versions! We had to strip them down, as they were manic. But we’d always wanted to make a record with complex arrangements – we were always too skint and too impatient, though. The way we made this record and wrote these songs – very slowly, bit by bit, over months and years – meant we could add ideas as they came to us in a natural way. It felt like the right thing for the songs.

INTERVIEW: JASON ANDERSON