CSNY's "Doom Tour" exhumed, and reconstructed into an ideal show from their stadium excursion... To call this live compilation from CSNY’s 1974 tour “long-awaited” is, on one level, an act of revisionism. Certainly, it has been a long time coming, but it’s also true that in the intervening 40 years, the competing egos of CSNY have done their best to suggest that if the tour itself wasn’t best forgotten, there was nothing to be gained by revisiting it. Indeed, Stephen Stills started suppressing interest before the tour had even taken place, famously telling Cameron Crowe in Creem: “We did one for the art and the music, one for the chicks. This one’s for the cash.” Less well remembered is how Stills immediately qualified that jokey remark, saying that “the music is real good, like it’s never been before. And that’s probably because everybody’s matured as musicians.” Neil Young, in his book, Waging Heavy Peace, was rather less ebullient, saying: “Most of these stadium shows were just no good. The technology was not there for the sound. It was all about the egos of everyone. The group was more into showboating than music. It was a huge disappointment.” So was it just one for the money? Well, it’s true that 1974 found CSNY in a state of flux. After their anointment as the American Beatles, post-Woodstock in 1969, their solo careers had waned somewhat. Even Young had shed some of the commercial lustre of Harvest, and was in a state of emotional turmoil. He had recorded but not released Tonight’s The Night, inspired by the death of Danny Whitten. And the similarly dark On The Beach, its bitter tone coloured by Young’s troubled relationship with Carrie Snodgress, was about to be issued. These records are now seen as creative high-points, but they weren’t considered commercial at the time. Whether CSNY actually split up in between times is a moot point. Various permutations had managed to rub along onstage and record, but the full quartet only appeared together three times in four years. In spring 1973, they had made an unsuccessful attempt at recording an album in Hawaii, where David Crosby’s schooner was moored, moving on to Young’s Broken Arrow ranch, but the results were unsatisfactory. Still, something must have clicked, because rumours about a tour persisted. It took the recruitment of veteran promoter Bill Graham to get the wheels moving. Graham had just taken Bob Dylan on a tour of indoor arenas, and his ambitions for CSNY were grander still. A two-month tour of American sports stadia was arranged, plus a valedictory date at Wembley Stadium in London: 31 shows in 24 cities. Corners were not cut. A line portrait of the group by Joni Mitchell was affixed to the tour crockery and luggage tags, and screen-printed onto the tour pillowcases. The group hopped between cities in Lear jets. Limousines were on standby at all times, but rarely used. Young preferred to travel with family and friends in a mobile home which he called “Mobil-Obil”. It was later replaced by “Sam Sleaze”, an old gospel tourbus. But the sense of dislocation within the group wasn’t just caused by the size of the venues, or the travel arrangements. There was a good deal of superstar excess at play too. Cocaine had replaced marijuana as the drug of choice, doing nothing to create a communal ethic. CSNY’s musical ambitions were grandiose. The plan was to avoid reprising old material. Back catalogue, when played, would be rearranged. Crosby talked of a setlist consisting of 44 songs. They managed 40 on the opening night, then trimmed back to 30, with each set including acoustic and electric passages, and individual showcases. None of which prepares you for the extraordinary clarity of the sound on this album, which has been assembled by Nash from the 10 shows which were professionally recorded to represent an ideal night on the tour. That isn’t to say it all sounds harmonious. Playing such large venues with inadequate equipment clearly strained the voices, so there are some rough larynxes on display on Stills’ “Love The One You’re With” and the croaky cover of The Beatles’ “Blackbird”. (Stills’ throatiness is put to good use on the bluesy “Word Game”, though.) Superstar egos aside, a different kind of tension is evident. The world had moved on since Woodstock. The politics of 1974 were stalked by paranoia, fear and loathing. These were the last days of the Nixon administration. Crosby’s banter includes a joke about the 18-minute gap on the Watergate tapes. There’s even a musical tribute to the disgraced president, “Goodbye Dick”, composed in haste by Young after Nixon’s resignation on August 9 (and performed on August 14). It’s no “Ohio”, being a jokey banjo lament lasting no more than a minute, but it does capture the malignant spirit of the times. It’s also evident that Young is performing on a different level to his bandmates. Creatively, he’s on fire, while CSN are doused, or prone to indulgence. So, while “Almost Cut My Hair” assumes a somewhat pensive air, protest songs “Fieldworker” and “Immigration Man” are too literal to be effective. Including “Goodbye Dick”, there are five unreleased Young songs. “Hawaiian Sunrise” is a frivolous South Seas lilt. “Love Art Blues” is a self-mocking country strum (“My songs are all so long/And my words are all so sad”). “Traces” is a typical exploration of alienation. And the eight-minute “Pushed It Over The End” is a sprawling exercise in uncertain time signatures and whacked-out emotions. But there’s also an incendiary “Revolution Blues” with Young howling like a dog about the lepers of Laurel Canyon; a gospel-tinged “Helpless”, and a truly fantastic rendition of “On The Beach”, all malign electricity and coiled neuroses. “Old Man” is elevated by its harmonies, while “Long May You Run” manages to sound like a farewell toast to the hippy ideals which CSNY once appeared to represent, its fragile mood elevated by Stills’ fractured harmonies. The album ends, as it must, with “Ohio”. Maybe, with Nixon gone, there’s a note of triumph buried beneath its thrashing riff, but the pervasive mood is one of melancholy fury – which qualifies it all the better to be the band’s swansong. The 3CD box has a bonus DVD with decent live footage from Landover, Maryland and Wembley. There is a limited wooden boxset with 6 LPs, Blu-ray audio disc, and book. And a single CD version, with 16 tracks. Alastair McKay

CSNY’s “Doom Tour” exhumed, and reconstructed into an ideal show from their stadium excursion…

To call this live compilation from CSNY’s 1974 tour “long-awaited” is, on one level, an act of revisionism. Certainly, it has been a long time coming, but it’s also true that in the intervening 40 years, the competing egos of CSNY have done their best to suggest that if the tour itself wasn’t best forgotten, there was nothing to be gained by revisiting it. Indeed, Stephen Stills started suppressing interest before the tour had even taken place, famously telling Cameron Crowe in Creem: “We did one for the art and the music, one for the chicks. This one’s for the cash.”

Less well remembered is how Stills immediately qualified that jokey remark, saying that “the music is real good, like it’s never been before. And that’s probably because everybody’s matured as musicians.” Neil Young, in his book, Waging Heavy Peace, was rather less ebullient, saying: “Most of these stadium shows were just no good. The technology was not there for the sound. It was all about the egos of everyone. The group was more into showboating than music. It was a huge disappointment.”

So was it just one for the money? Well, it’s true that 1974 found CSNY in a state of flux. After their anointment as the American Beatles, post-Woodstock in 1969, their solo careers had waned somewhat. Even Young had shed some of the commercial lustre of Harvest, and was in a state of emotional turmoil. He had recorded but not released Tonight’s The Night, inspired by the death of Danny Whitten. And the similarly dark On The Beach, its bitter tone coloured by Young’s troubled relationship with Carrie Snodgress, was about to be issued. These records are now seen as creative high-points, but they weren’t considered commercial at the time.

Whether CSNY actually split up in between times is a moot point. Various permutations had managed to rub along onstage and record, but the full quartet only appeared together three times in four years. In spring 1973, they had made an unsuccessful attempt at recording an album in Hawaii, where David Crosby’s schooner was moored, moving on to Young’s Broken Arrow ranch, but the results were unsatisfactory. Still, something must have clicked, because rumours about a tour persisted. It took the recruitment of veteran promoter Bill Graham to get the wheels moving. Graham had just taken Bob Dylan on a tour of indoor arenas, and his ambitions for CSNY were grander still. A two-month tour of American sports stadia was arranged, plus a valedictory date at Wembley Stadium in London: 31 shows in 24 cities. Corners were not cut. A line portrait of the group by Joni Mitchell was affixed to the tour crockery and luggage tags, and screen-printed onto the tour pillowcases. The group hopped between cities in Lear jets. Limousines were on standby at all times, but rarely used.

Young preferred to travel with family and friends in a mobile home which he called “Mobil-Obil”. It was later replaced by “Sam Sleaze”, an old gospel tourbus. But the sense of dislocation within the group wasn’t just caused by the size of the venues, or the travel arrangements. There was a good deal of superstar excess at play too. Cocaine had replaced marijuana as the drug of choice, doing nothing to create a communal ethic.

CSNY’s musical ambitions were grandiose. The plan was to avoid reprising old material. Back catalogue, when played, would be rearranged. Crosby talked of a setlist consisting of 44 songs. They managed 40 on the opening night, then trimmed back to 30, with each set including acoustic and electric passages, and individual showcases. None of which prepares you for the extraordinary clarity of the sound on this album, which has been assembled by Nash from the 10 shows which were professionally recorded to represent an ideal night on the tour.

That isn’t to say it all sounds harmonious. Playing such large venues with inadequate equipment clearly strained the voices, so there are some rough larynxes on display on Stills’ “Love The One You’re With” and the croaky cover of The Beatles’ “Blackbird”. (Stills’ throatiness is put to good use on the bluesy “Word Game”, though.)

Superstar egos aside, a different kind of tension is evident. The world had moved on since Woodstock. The politics of 1974 were stalked by paranoia, fear and loathing. These were the last days of the Nixon administration. Crosby’s banter includes a joke about the 18-minute gap on the Watergate tapes. There’s even a musical tribute to the disgraced president, “Goodbye Dick”, composed in haste by Young after Nixon’s resignation on August 9 (and performed on August 14). It’s no “Ohio”, being a jokey banjo lament lasting no more than a minute, but it does capture the malignant spirit of the times.

It’s also evident that Young is performing on a different level to his bandmates. Creatively, he’s on fire, while CSN are doused, or prone to indulgence. So, while “Almost Cut My Hair” assumes a somewhat pensive air, protest songs “Fieldworker” and “Immigration Man” are too literal to be effective. Including “Goodbye Dick”, there are five unreleased Young songs. “Hawaiian Sunrise” is a frivolous South Seas lilt. “Love Art Blues” is a self-mocking country strum (“My songs are all so long/And my words are all so sad”). “Traces” is a typical exploration of alienation. And the eight-minute “Pushed It Over The End” is a sprawling exercise in uncertain time signatures and whacked-out emotions.

But there’s also an incendiary “Revolution Blues” with Young howling like a dog about the lepers of Laurel Canyon; a gospel-tinged “Helpless”, and a truly fantastic rendition of “On The Beach”, all malign electricity and coiled neuroses. “Old Man” is elevated by its harmonies, while “Long May You Run” manages to sound like a farewell toast to the hippy ideals which CSNY once appeared to represent, its fragile mood elevated by Stills’ fractured harmonies.

The album ends, as it must, with “Ohio”. Maybe, with Nixon gone, there’s a note of triumph buried beneath its thrashing riff, but the pervasive mood is one of melancholy fury – which qualifies it all the better to be the band’s swansong.

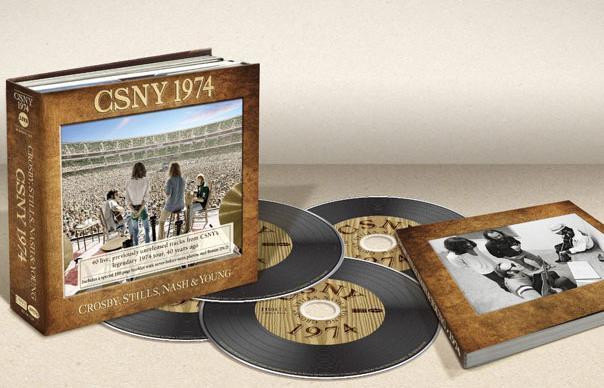

The 3CD box has a bonus DVD with decent live footage from Landover, Maryland and Wembley. There is a limited wooden boxset with 6 LPs, Blu-ray audio disc, and book. And a single CD version, with 16 tracks.

Alastair McKay