On its original release in November 1969, the album we now know as Space Oddity was simply called David Bowie. Confusingly, this had also been the title of his debut album of wonky music-hall released on Deram in 1967. It’s tempting to think that all the subsequent albums are really just called David Bowie, too – just as all the astronauts in his son’s debut film, Moon, are called Sam Bell. Looked at this way, Bowie’s whole career is a series of rebooted clones, or Timelord regenerations, each with the front to say, no, really, this time this is the real me: the befrocked rocker; the glambisexual space-pirate; the skeletal disco king; the abject ambient alien; the stadium-pop crooner, the heritage pop icon… Uniquely, on this album, Bowie himself doesn’t yet seem sure of his motivation or who he’s supposed to be. He’d secured his latest deal on the strength of “Space Oddity”, originally composed back when he was operating as part of performance troupe Feathers. Expanded from an acoustic guitar/stylophone ditty into a kind of psychedelic “Sound Of Silence” via the glorious ham of producer Gus Dudgeon, and released with opportunistic aplomb in the week of the Apollo 11 moonshot, it gave him his first hit single after five years of hustling. But the shamelessness seems to have embarrassed him almost immediately. Production for the LP was handed to Tony Visconti, and rather than explore his suddenly commercial cosmic anomie, Bowie instead recycled a motley ragbag of songs from the previous few years. So following the interstellar single, the album comes back to down to earth with the bump and grind of the scruffy, Stonesy “Unwashed and Somewhat Slightly Dazed” and “Janine”, takes a folksy turn on the lovely acoustic confessionals “Letter To Hermione” and “An Occasional Dream”, recruits a 50-piece orchestra for the fruitcake Buddhist showtune “Wild-Eyed Boy From Freecloud”, has a brief flashback to Anthony Newley-ish melodrama on the shoplifting sketch “God Knows I’m Good” and builds to an unconvincing climax with the would-be hippy anthem, “Memory Of A Free Festival”. Unsurprisingly the album proved to be an utter failure to launch, and didn’t even chart until its post-Ziggy rerelease and repackage in 1972. The one track here that might have given you an inkling in 1969 that Bowie was not just a one-shot is “Cygnet Committee”. A mad, rambling, nine-minute ballad of betrayal, disillusionment and dejection, the song certainly draws on Dylan (“the love machine lumbers down desolation rows”), but suggests Bowie emerging from the hippy era (the original cover featured him with a shaggy perm, looking like Paul Nicholas) into a more individual, if more cynical, artistic focus. The additional disc of 40th-anniversary rarities adds little to the original LP. Previously unreleased demos of “Space Oddity” and “An Occasional Dream”, recorded with John Hutchinson, emphasise the full extent of Bowie’s Simon-Garfunkely inclinations after the demise of Feathers. The Dave Lee Travis Radio Session version of “Let Me Sleep Beside You” (“It’s rather ethereal, actually,” insists a primly proper Bowie, bantering with a Bumfluffed Cornflake), makes plain the Viscontified hard rock direction to come on The Man Who Sold The World. The Italian version of “Space Oddity”, “Ragazzo Solo, Ragazza Sola” (rewritten rather than translated as a kitsch weepie) suggests just how desperate Bowie was for success in any market. In a suitably shameless attempt to bring the old spaceman up to date for this latest reissue, Bowie has also sanctioned a remix application which allows to you to tweak the stylophone and strings on “Space Oddity” to your heart’s content on your iPhone – which in the year of The Beatles™: Rock Band™ already looks a little quaint. As Bowie’s back catalogue looks set for eternal commercial return, surely it could be exploited with a little more wit? You can already imagine the 50th anniversary multi-media editions, executively directed by Duncan Jones, where, like in one of those multi-Dr episodes of Who , the whole mad parade of personae finally meet and compete in CGI heaven – and the issue of the real David Bowie is finally resolved. STEPHEN TROUSSE Latest and archive album reviews on Uncut.co.uk Latest music and film news on Uncut.co.uk

On its original release in November 1969, the album we now know as Space Oddity was simply called David Bowie. Confusingly, this had also been the title of his debut album of wonky music-hall released on Deram in 1967.

It’s tempting to think that all the subsequent albums are really just called David Bowie, too – just as all the astronauts in his son’s debut film, Moon, are called Sam Bell. Looked at this way, Bowie’s whole career is a series of rebooted clones, or Timelord regenerations, each with the front to say, no, really, this time this is the real me: the befrocked rocker; the glambisexual space-pirate; the skeletal disco king; the abject ambient alien; the stadium-pop crooner, the heritage pop icon…

Uniquely, on this album, Bowie himself doesn’t yet seem sure of his motivation or who he’s supposed to be. He’d secured his latest deal on the strength of “Space Oddity”, originally composed back when he was operating as part of performance troupe Feathers. Expanded from an acoustic guitar/stylophone ditty into a kind of psychedelic “Sound Of Silence” via the glorious ham of producer Gus Dudgeon, and released with opportunistic aplomb in the week of the Apollo 11 moonshot, it gave him his first hit single after five years of hustling.

But the shamelessness seems to have embarrassed him almost immediately. Production for the LP was handed to Tony Visconti, and rather than explore his suddenly commercial cosmic anomie, Bowie instead recycled a motley ragbag of songs from the previous few years.

So following the interstellar single, the album comes back to down to earth with the bump and grind of the scruffy, Stonesy “Unwashed and Somewhat Slightly Dazed” and “Janine”, takes a folksy turn on the lovely acoustic confessionals “Letter To Hermione” and “An Occasional Dream”, recruits a 50-piece orchestra for the fruitcake Buddhist showtune “Wild-Eyed Boy From Freecloud”, has a brief flashback to Anthony Newley-ish melodrama on the shoplifting sketch “God Knows I’m Good” and builds to an unconvincing climax with the would-be hippy anthem, “Memory Of A Free Festival”.

Unsurprisingly the album proved to be an utter failure to launch, and didn’t even chart until its post-Ziggy rerelease and repackage in 1972. The one track here that might have given you an inkling in 1969 that Bowie was not just a one-shot is “Cygnet Committee”.

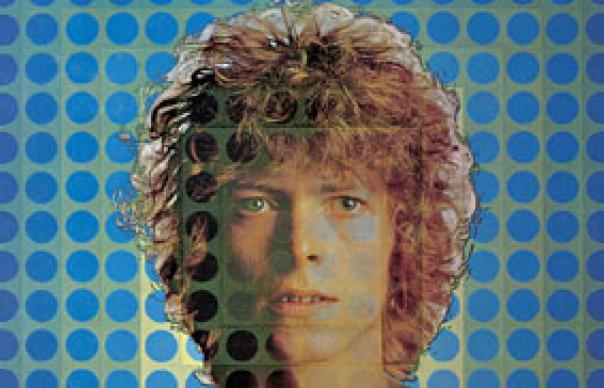

A mad, rambling, nine-minute ballad of betrayal, disillusionment and dejection, the song certainly draws on Dylan (“the love machine lumbers down desolation rows”), but suggests Bowie emerging from the hippy era (the original cover featured him with a shaggy perm, looking like Paul Nicholas) into a more individual, if more cynical, artistic focus.

The additional disc of 40th-anniversary rarities adds little to the original LP. Previously unreleased demos of “Space Oddity” and “An Occasional Dream”, recorded with John Hutchinson, emphasise the full extent of Bowie’s Simon-Garfunkely inclinations after the demise of Feathers.

The Dave Lee Travis Radio Session version of “Let Me Sleep Beside You” (“It’s rather ethereal, actually,” insists a primly proper Bowie, bantering with a Bumfluffed Cornflake), makes plain the Viscontified hard rock direction to come on The Man Who Sold The World. The Italian version of “Space Oddity”, “Ragazzo Solo, Ragazza Sola” (rewritten rather than translated as a kitsch weepie) suggests just how desperate Bowie was for success in any market.

In a suitably shameless attempt to bring the old spaceman up to date for this latest reissue, Bowie has also sanctioned a remix application which allows to you to tweak the stylophone and strings on “Space Oddity” to your heart’s content on your iPhone – which in the year of The Beatles™: Rock Band™ already looks a little quaint.

As Bowie’s back catalogue looks set for eternal commercial return, surely it could be exploited with a little more wit? You can already imagine the 50th anniversary multi-media editions, executively directed by Duncan Jones, where, like in one of those multi-Dr episodes of Who , the whole mad parade of personae finally meet and compete in CGI heaven – and the issue of the real David Bowie is finally resolved.

STEPHEN TROUSSE