Though the end of his professional life was spectacularly well managed, the start of David Bowie’s career was – as we’ve lately been reminded by the Finding Fame documentary – rather less orderly. Given his continuing run of flop singles, and a misunderstood, poorly timed debut album, David Jones didn’t become David Bowie the moment he changed his name in 1966. So when does the David Bowie we know and love really start?

As early as 1973, his record companies struggled with this same question: trying gamely to reconcile the eyebrowless glam rock of his present with the characterful but variable recordings of his recent past, Deram’s World Of David Bowie (a collection of singles and offcuts) updated its 1970 cover to reflect its maker’s messianic reinvention. Both 1969’s David Bowie and 1970’s The Man Who Sold The World likewise received big-booted, Ziggy-appropriate upgrades. The former was renamed after its hit single, becoming Space Oddity.

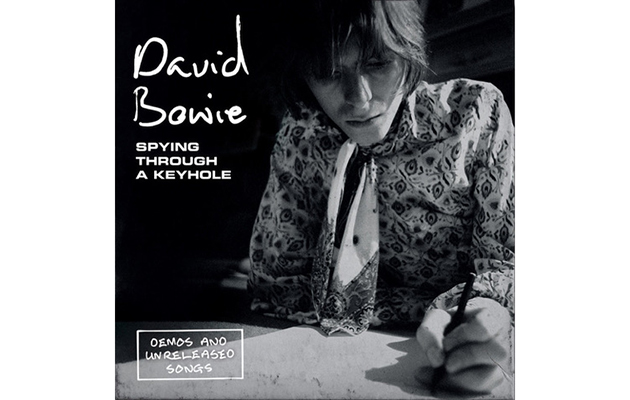

Fifty years on from that song’s release in July 1969, this pair of charming 7-inch boxsets underline much the same point, that “Space Oddity” represents the singer’s first major breakthrough. The first box, Spying Through A Keyhole, presents the song both as a fragment and in a developing version performed with guitarist John “Hutch” Hutchinson. The second box, Clareville Grove Demos (named after Bowie’s 1968 address in Kensington, where he lived with Hermione Farthingale at No 22), begins with the feedbacky, near-complete demo version you may have heard on the now-deleted 40th-anniversary edition of the 1969 album. It ends with a morse code SOS, a meaningful plea for help. Who will hear him and come to his aid?

Comprising demos from 1968-9, when he had been dropped by Deram, these two sets find Bowie observing greatness through a telescope, but yet actually to touch down on its surface. Spying… in particular shows Bowie almost pointedly earthbound, as was Ray Davies in the same period: relishing the everyday. Davies manqué was one of the modes Bowie employed on his debut, and a bleak “London Boys”-style documentary detail is still the order of the day in the previously unknown songs here.

It’s all about the kitchen for Bowie in 1967-8, and he leaves you in no doubt which is the most important meal of the day. “Mother Grey”, whose son has left home, wonders while wiping a picture frame, “how breakfast will ever be the same”. The Dylanesque “Love All Around” references the kitchen door. The contemporary song “When I’m Five” (not included here, though one hopes it might possibly emerge later, in which Bowie skilfully inhabits the voice of a child) makes narrative capital out of a dropped piece of toast.

Sonically and creatively, these demos reflect their domestic environment, the realm of the historically valuable rather than the mind-blowing. In our Bowie tourism industry everyone’s pretty much agreed on the main attractions, but there are some lesser-praised delights, as here, under-reviewed by TripAdvisor. Twelve-string demos of “London Bye Ta Ta” (adapted later as “Threepenny Pierrot” for Lindsay Kemp’s Pierrot In Turquoise) and “In The Heat Of The Morning” both show how Bowie could locate a strong melody over very weird chords, but it’s not as if you can hear him inching towards his breakthrough. It’s just not there, then suddenly it is.

Order the latest issue of Uncut online and have it sent to your home!

If, however, we follow “Space Oddity” down one of its more obvious metaphorical avenues and suggest that it’s about creative escape, there are some signs of life to be spotted in Bowie’s demo universe. In “Threepenny Joe”, the singer and his girl – in a Beatles/Barretty mode – attend a sideshow performance by the titular Joe, only to discover that his performance has some unsettling properties. In the two versions of “Angel Angel Grubby Face” on here, the escape is more literal: from the confines of “Factory Street” to the countryside, a specific “13 miles” away (from 22 Clareville Grove to Beckenham is about 11).

The second version is downbeat, underlining that this is still a Ray Davies kind of tale and that escape is only offered on a day return basis. When the excerpt of “Space Oddity” appears at the end of this side, it really does feel like a giant leap for Bowiekind. It must have felt like a huge relief. Adrift from a label, with other interests on the go, Bowie was in danger of slipping through rock’n’roll’s cracks. A promotional film bankrolled by his manager, Ken Pitt, attempted to package together Bowie’s songs and his interest in mime with (as we discovered on its release two decades later) jaunty and eccentric results. Musically, though, his proposition was unstable. A promising producer, Tony Visconti, was now in his circle, but his performance-art trio Feathers had lately lost one of its members, Bowie’s girlfriend Hermione Farthingale.

Now, with the folk pop of Simon & Garfunkel as his inspiration, he embraced the possibilities of the duo, performing with ex-Buzz, now Feathers man John Hutchinson. Resourceful Bowie fans have heard some fruits of this collaboration before in unofficial guises like ‘The Revox Tape’, ‘Sussex University 11/2/69’, ‘Publisher Demos’ and so on. If all those and the present release all come from the same place, it’s curious that the likes of “Letter To Hermione” and “When I’m Five” aren’t included, but for the moment – with mighty impressive audio restoration by Andy Walter at Abbey Road – we can hear excerpted highlights from that tape.

By now (likely late January–early February 1969), “Space Oddity” is nearly there, the logic problems in the lyrics (“I think my term on Earth is nearly through”? Needs work: not actually on Earth, but in spacecraft!!!) all fixed, and an arrangement pretty well sorted, Hutch playing Ground Control to Bowie’s Major Tom. “Lover To The Dawn” alights on a lovely melody, which will later form the basis of “Cygnet Committee”, Bowie’s sideways look at the counterculture. Here it personifies night and day as on-again, off-again lovers (“Don’t throw your heart at the clouded moon…”).

Bowie and Hutch are beautifully in sync throughout. They can do robust folk-club strutting like the weird and curdled fairy story “Ching A Ling” (retained from the repertoire of Turquoise, a pre-Feathers trio) or “Let Me Sleep Beside You”. Getting more ethereal, they elevate Roger Bunn’s composition “Life Is A Circus” into something beyond its rather corny lyric (“Life is a circus/It’s notta fair/Life is a hard road/When you’re not there…”). Harmonies simply don’t come much closer than those the pair achieve on “An Occasional Dream”, which looks back on a lost love. If it’s about Hermione, then it will have been written when the loss was still raw.

As the pre-publicity advises us, in audio terms these are not the finished work. But in a way that’s a fitting kind of Bowie experience: work in progress by an artist who was himself always in progress. Duly, on a couple of quiet occasions on the Spying… set, it’s possible to discern some faint, sped-up voices in the background on the tape. It’s tempting to think of them as the ghosts of the Laughing Gnome, but they’re simply the traces of other fleeting moments, created and rejected, as Bowie headed inexorably towards his countdown.