40th anniversary clean up shows the devil in the detail...

Ziggy Stardust: The Motion Picture – the album of Bowie’s 1973 ‘retirement’ show at the Hammersmith Odeon – was only released in 1983, and it was the first Bowie album I ever bought. The electric atmosphere of that night, when Ziggy’s time took its last cigarette, made the studio LP, when I eventually heard it much later, seem pale and restrained by comparison, and I’ve never quite been able to shake that feeling.

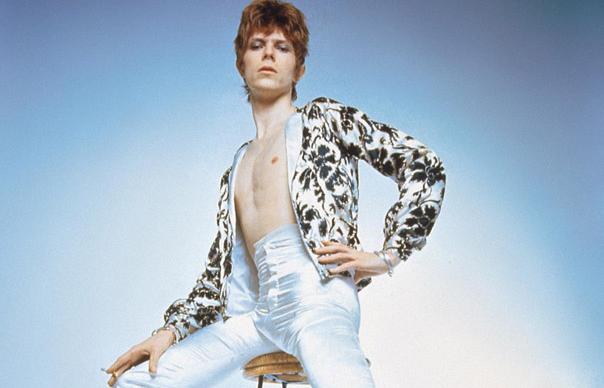

Try this thought experiment, though: put yourself in Bowie’s kinky boots, back in late 1971, when he began work on this songbook. ‘Glitter rock’ (not glam yet) was little more than a single T.Rex TOTP appearance; Slade, Sweet, Mud, Gary Glitter et al were nowhere to be seen; the ‘concept album’ was still in the hands of prog rockers like King Crimson, Yes and Genesis. For an artist like Bowie, who had already tried on several stylistic hats in a series of different strikes on the charts with little success, this was surely a huge gamble. If anyone knew him at all, it was as the ringletted hippy of “Space Oddity” or the flouncy, cross-dressing queen of The Man Who Sold The World. To launch himself as a cropped, jumpsuited, bovver-boots rocker, brandishing an unwieldily-titled album which never quite made it clear whether he was posing as this Ziggy character, or merely singing his story, was, frankly, a daring step into the dark.

The apex of Bowie’s glam period was, really, the Brechtian panto of Aladdin Sane – in many ways a very different, far more sophisticated record than Ziggy Stardust. But this 40th anniversary remaster certainly opens up some new crevices in the sound, allowing small production details to shine through like never before: the little violin-eddies at the end of “Five Years”, the razor-edge rimshots on “Soul Love”, and, on “Starman”, “Ziggy Stardust” and most others, the richly textured doubling of Bowie’s acoustic guitars with Mick Ronson’s phlegmatic Les Paul.

And yet the clean-up serves also to accentuate the slightly clinical nature of Ziggy Stardust. It’s an experimental record, in the sense that Bowie was trying out an unknown formula – a concept album that almost, but not quite, tells a story; a tale of a space-age future rock group that sometimes sounds like a survival from the days of rock ’n’roll. The opening two tracks are decidedly undynamic: “Five Years” is a plodder, a dejected yelp from a disaffected hipster who’s just discovered apocalypse is round the corner. “Soul Love”, which paints a panorama of hippy indolence, is unbearably slow. Which makes the cojones-grabbing entrance of “Moonage Daydream” that much more powerful: something freaky starts to flicker at the mirror’s edge, a track that seems worthy of Ziggy’s off-world provenance. This is where the album picks up the slack, although Woody Woodmansey’s drums curiously lack presence, a drawback even this master hasn’t been able to fix. Bowie’s vocal performances are unusually passionless, too, apart from “Suffragette City”’s pumped-up hedonism and the bawling drama of “Rock ’n’ Roll Suicide”.

The real wonder, it retrospect, is how Bowie got away with it. After all, Ziggy Stardust makes out it’s a concept album but leaves you to infer a ‘story’ from a song sequence with plenty of gaps; and he never quite seems to work out if he IS Ziggy on record, or if he’s merely telling Ziggy’s story from multiple perspectives. But that’s what makes Ziggy Stardust what it is: with The Beatles gone, it’s the first self-conscious pop star album – a record about fame, about rock’s messianic potential and its always-threatening end (you could read the “five years, that’s all we got” scenario as a metaphor for the truncated lifespan of the average pop idol). As Bowie’s subsequent path showed, the key to rock god immortality was to become a shapeshifting deity, perpetuating himself through self-transformation.

Rob Young

Q+A

Ken Scott

Ziggy Stardust obviously marked a turning point for Bowie – how clear was that during the recording?

It wasn’t clear at all. It’s still not to me. Listening now I can almost see Hunky Dory and Ziggy being a double album. They were recorded so close together. “Queen Bitch” would certainly fit in with anything on Ziggy Stardust. No concept was discussed at all. The only thing said was that the album was going to be more rock and roll.

How involved were the rest of the group in the way it sounded?

It was a team effort. We all had input. It wouldn’t have been what it was without Ronno’s playing and orchestral arrangements, but it wouldn’t have been what it was/is without any of the team.

Were there any particular difficulties, or special high points, while recording this album?

KS: There were no difficulties. As far as highlights go, the whole thing. Every time David did one of his one-take master vocal performances or Ronno went down and did exactly what was needed without any prior discussion. I guess, as we’re still discussing it 40 years on, it worked.

INTERVIEW: ROB YOUNG

40th anniversary clean up shows the devil in the detail…

Ziggy Stardust: The Motion Picture – the album of Bowie’s 1973 ‘retirement’ show at the Hammersmith Odeon – was only released in 1983, and it was the first Bowie album I ever bought. The electric atmosphere of that night, when Ziggy’s time took its last cigarette, made the studio LP, when I eventually heard it much later, seem pale and restrained by comparison, and I’ve never quite been able to shake that feeling.

Try this thought experiment, though: put yourself in Bowie’s kinky boots, back in late 1971, when he began work on this songbook. ‘Glitter rock’ (not glam yet) was little more than a single T.Rex TOTP appearance; Slade, Sweet, Mud, Gary Glitter et al were nowhere to be seen; the ‘concept album’ was still in the hands of prog rockers like King Crimson, Yes and Genesis. For an artist like Bowie, who had already tried on several stylistic hats in a series of different strikes on the charts with little success, this was surely a huge gamble. If anyone knew him at all, it was as the ringletted hippy of “Space Oddity” or the flouncy, cross-dressing queen of The Man Who Sold The World. To launch himself as a cropped, jumpsuited, bovver-boots rocker, brandishing an unwieldily-titled album which never quite made it clear whether he was posing as this Ziggy character, or merely singing his story, was, frankly, a daring step into the dark.

The apex of Bowie’s glam period was, really, the Brechtian panto of Aladdin Sane – in many ways a very different, far more sophisticated record than Ziggy Stardust. But this 40th anniversary remaster certainly opens up some new crevices in the sound, allowing small production details to shine through like never before: the little violin-eddies at the end of “Five Years”, the razor-edge rimshots on “Soul Love”, and, on “Starman”, “Ziggy Stardust” and most others, the richly textured doubling of Bowie’s acoustic guitars with Mick Ronson’s phlegmatic Les Paul.

And yet the clean-up serves also to accentuate the slightly clinical nature of Ziggy Stardust. It’s an experimental record, in the sense that Bowie was trying out an unknown formula – a concept album that almost, but not quite, tells a story; a tale of a space-age future rock group that sometimes sounds like a survival from the days of rock ’n’roll. The opening two tracks are decidedly undynamic: “Five Years” is a plodder, a dejected yelp from a disaffected hipster who’s just discovered apocalypse is round the corner. “Soul Love”, which paints a panorama of hippy indolence, is unbearably slow. Which makes the cojones-grabbing entrance of “Moonage Daydream” that much more powerful: something freaky starts to flicker at the mirror’s edge, a track that seems worthy of Ziggy’s off-world provenance. This is where the album picks up the slack, although Woody Woodmansey’s drums curiously lack presence, a drawback even this master hasn’t been able to fix. Bowie’s vocal performances are unusually passionless, too, apart from “Suffragette City”’s pumped-up hedonism and the bawling drama of “Rock ’n’ Roll Suicide”.

The real wonder, it retrospect, is how Bowie got away with it. After all, Ziggy Stardust makes out it’s a concept album but leaves you to infer a ‘story’ from a song sequence with plenty of gaps; and he never quite seems to work out if he IS Ziggy on record, or if he’s merely telling Ziggy’s story from multiple perspectives. But that’s what makes Ziggy Stardust what it is: with The Beatles gone, it’s the first self-conscious pop star album – a record about fame, about rock’s messianic potential and its always-threatening end (you could read the “five years, that’s all we got” scenario as a metaphor for the truncated lifespan of the average pop idol). As Bowie’s subsequent path showed, the key to rock god immortality was to become a shapeshifting deity, perpetuating himself through self-transformation.

Rob Young

Q+A

Ken Scott

Ziggy Stardust obviously marked a turning point for Bowie – how clear was that during the recording?

It wasn’t clear at all. It’s still not to me. Listening now I can almost see Hunky Dory and Ziggy being a double album. They were recorded so close together. “Queen Bitch” would certainly fit in with anything on Ziggy Stardust. No concept was discussed at all. The only thing said was that the album was going to be more rock and roll.

How involved were the rest of the group in the way it sounded?

It was a team effort. We all had input. It wouldn’t have been what it was without Ronno’s playing and orchestral arrangements, but it wouldn’t have been what it was/is without any of the team.

Were there any particular difficulties, or special high points, while recording this album?

KS: There were no difficulties. As far as highlights go, the whole thing. Every time David did one of his one-take master vocal performances or Ronno went down and did exactly what was needed without any prior discussion. I guess, as we’re still discussing it 40 years on, it worked.

INTERVIEW: ROB YOUNG