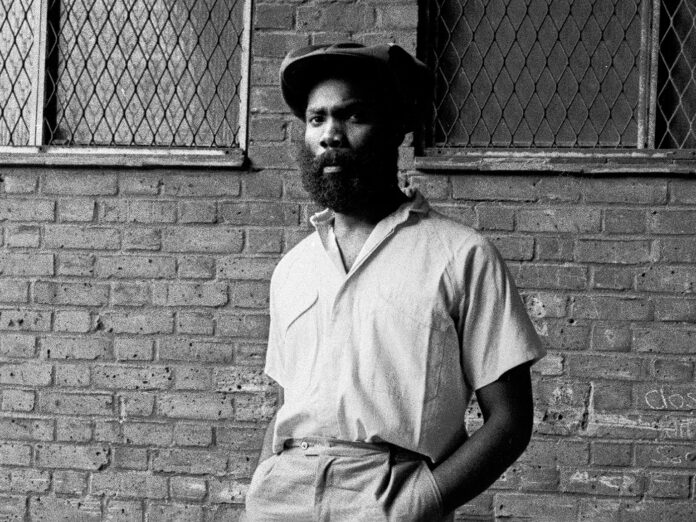

He went by many names. Blackbeard. The Dub Band. African Stone. The 4th Street Orchestra. Dennis Matumbi. Today, though, they simply call him Dennis Bovell MBE.

Bovell was one of the central figures in the great flowering of homegrown UK reggae in the 1970s and ’80s, and surely the most adaptable. A multi-instrumentalist, bandleader, sound system selector, chart hitmaker, architect of lovers rock, and an in-demand producer for everyone from dub poet Linton Kwesi Johnson to post-punk groups like The Pop Group and The Slits – Bovell did it all, and has the box of dusty dubplates to prove it.

Despite that silver he picked up in the Queen’s 2021 Birthday Honours, you could convincingly argue that Bovell hasn’t received the full recognition he deserves. Blame that rash of pseudonyms, perhaps – or that many of his productions probably got cut to acetate, played out at a dance and then filed away, their destiny having been realised. Well, if Bovell has been in any way overlooked, Sufferer Sounds is a major step to redress that balance.

This compilation has a backstory. Matthew Jones, proprietor of the Warp Records imprint Disciples, also runs the General Echo Reggae Disco at the Walthamstow Trades Hall in north London. In 2018, Dennis Bovell graced the decks, and Jones had a fanboy moment, quizzing Bovell on the provenance of various lost or forgotten tunes. That chat became an ongoing conversation, and soon the idea of Sufferer Sounds took shape: a collection of early obscurities and deep cuts, focused on and around the fertile period that Bovell spent with Jah Sufferer Sound System between 1976 and 1980.

Sufferer Sounds isn’t anything like a Greatest Hits. A compilation like that would undoubtedly include a track like Janet Kay’s “Silly Games”, a sultry reggae production written and produced by Bovell that hit No.2 in the summer of 1979 and was recently revived by director Steve McQueen for Lovers Rock, a film from his 2020 anthology series Small Axe. Instead, Sufferer Sounds features the track “Game Of Dubs”, a remix that pulls back Kay’s vocal, applying lashings of echo and delay and some pizzicato violin courtesy of collaborator Johnny T. It’s very much an alternate take, but one that shows Bovell at the peak of his powers.

By the time the music on Sufferer Sounds was made, Bovell already had a good decade of music-making under his belt. Born in Barbados, he moved to London in 1965 at the age of 12. His father ran a sound system playing blues parties to African diaspora communities across south London, and the young Bovell would attend and take notes. Soon, he was cutting dubplates at the recording studio at his school in Wandsworth, adapting well-known tunes and taking them out as one of the selectors for the Battersea sound system Jah Sufferer Sound, who would clash rival sounds like Jah Shaka and Lion Sound across the country.

In tandem, Bovell was honing his talents as the bandleader and guitarist in Matumbi – a live group formed, in part, to play backing band for visiting Jamaican vocalists like Ken Boothe and Johnny Clarke. But Matumbi also started recording original material and stepping out alone, and some nights Bovell would take to the mixing desk as the band played, remixing them live. The group developed some formidable chops – Bovell recalled how they blew The Wailers offstage at the Ethiopian famine relief concert in Edmonton in 1973, and some of that energy is evident on the two Matumbi tracks here, “Dub Planet” and “Fire Dub”.

All this early experience feeds into the music we hear on Sufferer Sounds, a collection of tracks that showcase Bovell’s compositional talents, adventurous dub production style and can-do, bootstrap attitude. Some tracks here, like The Dub Band’s “Dub Land” and “Blood Dem” – recorded under the name Dennis Matumbi – are early solo joints which Bovell created alone in his basement studio, layering tracks on a four-track TEAC machine: first drums, then bassline, then guitar and keys. The latter is particularly intense – a sepulchral number that Bovell says was inspired by his memories of Enoch Powell’s divisive “Rivers Of Blood” speech, as well as a watching of Roots, the 1977 American TV miniseries that followed the lineage of an African family from their enslavement through to abolition. Often Bovell would bring in a guest vocalist, but he sings this one himself, scrambling his vocals with whooshing edits. Sometimes, though, a stray line escapes: “You know I’m going back to Zion one day/Makes no difference if you change my name/In my heart I’ll remain the same…”

Elsewhere, tracks like “Suffrah Dub” and African Stone’s “Run Rasta Run” find Bovell in bandleader mode, assembling ensembles featuring hotshot personnel like Matumbi drummer Jah Bunny, guitarist-for-hire John Kpiaye and the Cuba-born horn player Rico Rodriguez, later of The Specials. Bovell was by no means a dub purist – on the contrary, on an album like 1981’s Brain Damage, he seemed driven to express the idea that dub reggae was flexible enough to encompass other genres – and backed by the right musicians he could put those ideas into practice. That seems to be the impulse behind a track like Young Lions’ “Take Dub” – a sort of reggae reimagining of Dave Brubeck’s “Take Five”, with the original’s shuffling jazz drums reconfigured into a tuff dub strut, and the original’s naggingly familiar saxophone line reinterpreted by the sessioneer Steve Gregory.

If you could rightly say a figure as versatile as Dennis Bovell had a superpower, it was in blending the rough with the smooth. By the 1970s, London audiences were tiring of the hellfire and damnation of Rastafarian reggae, and were ready for something a bit more sweet, cosmopolitan, female. Bovell was one of the prime movers behind lovers rock, a homegrown British sound blending Jamaican rocksteady with American soul music, often exploring themes of romantic love. Angelique’s “Cry” is a gem of the genre, marking the first-ever recorded performance by a future Bovell collaborator, Marie Pierre. The loveable “Jah Man”, meanwhile, is vocaled by another amateur, Errol Campbell – a young follower of Jah Sufferer Sound who Bovell plucked from the crowd and put on the mic. Bovell has a knack for taking these untrained voices and coaching them to a seamless, professional performance while keeping something of their wide-eyed innocence intact.

It was a matter of pride for Dennis Bovell that he would not be easily pigeonholed. All those pseudonyms had a dual purpose. For one, in the late ’70s, Bovell was extraordinarily prolific, churning out enough music that it made sense that he diversify, splitting his product across several projects. For another, it was a skilful feat of misdirection. Some sound systems would turn their nose up at homegrown British tunes, so by moving fast and flying under the radar he could sneak his tunes into the right record boxes without fear of prejudice.

Has it made his legacy harder to assess? Arguably. But the quality of music collected on Sufferer Sounds makes it hard to deny: in the field of UK reggae, Dennis Bovell was one of the greatest to ever do it.