Four years ago, when Brian Wilson finally finished work on the daddy of all lost masterpieces, Smile, he did Beach Boys fans a huge favour, but also solved one of the band’s most enduring and enticing mysteries. What would people do with no need to search for that holy grail: The Great Lost Beach Boys album? Dennis Wilson doesn’t just provide lost albums – his is almost an entirely lost career. With his only completed solo album, Pacific Ocean Blue, long deleted and its mythical successor Bambu never released, Dennis was feted chiefly by fans who had checked the credits of post-Pet Sounds albums and realised that the hirsute, handsome one on the drums had a surprisingly keen strike rate. “Cuddle Up” from Carl & The Passions/So Tough? That was his? “Forever” was Dennis too? Who knew? Well, The Beach Boys did, of course, but it wasn’t as though they did much to nurture him. “He was under-appreciated in our band,” said Al Jardine, and certainly, using Dennis’s songs could have helped the Beach Boys out of the spot they found themselves in in the mid-70s. Instead, when 15 Big Ones came out in 1975, effectively marking the band’s inexorable decline into becoming an oldies act, Dennis took the songs he had co-written with old pal Gregg Jakobson to Jim Guercio, head of Caribou Records – and duly became the first Beach Boy to release a solo album. Pacific Ocean Blue went head-to-head with The Beach Boys’ next album Love You, Dennis outsold his brothers by two-to-one. In the thirty years since, Pacific Ocean Blue’s reputation has risen with the superlatives lavished up on it by fans such as The Verve, Primal Scream and The Charlatans. Unavailability has also played its part in pumping up the myth – so much so that you wonder if, heard in 2008, these songs stand to disappoint. In fact, key moments of Pacific Ocean Blue square dramatically up to your loftiest expectations. It’s hard to talk about the opener, the Carl Wilson-assisted “River Song” in anything other than the very terminology it deploys: rising torrents of gospel harmonies, the freshwater piano trickle that starts the thing off; and the unstoppable current of Wilson’s voice, blurring nature and love into an irresistible all-consuming force. “Rainbows” is a love-drunk paean to life lived large carried effortlessly by the pistons-hissing chug of its own backing track. “Farewell My Friend” is a requiem to just-deceased Beach Boys’ associate Otto Hinsche, apparently written at the piano in a single rhapsodic outpouring to the astonishment of all present. These are songs you could live your life to, were it not for the fact that its creator expired doing just that. You can guess what kind of a husband Dennis was to his four wives by cocking an ear to “Time”. “I’m the kind of guy who loves to mess around,” sings the sad miscreant more out of regret than pride. If Wilson’s ex-wives still seem anguished by his passing, “Thoughts Of You” goes some way to explaining why. Moving from hair-shirt minor chords and hushed, penitent assurances into a major-chord sunburst of temporary resolution, he sings “All things that live, one day must die” – and his voice hurts like you’ve never heard a Beach Boy’s voice hurt before. On Pacific Ocean Blue, Dennis’s two sides – the boozy bon viveur and repentant child – often co-exist within the same song. Not so the songs from Bambu. The hoarse, hungover croak evokes Harry Nilsson, whose recreational habits mirrored Dennis’s own. And like Nilsson’s underrated 1972 album Nilsson Schmilsson, Bambu veers wildly between ribald, roister-doistering and achingly tender declarations of love. The reasons were simple enough here. The former songs – “School Girl”; “He’s A Bum”, “Wild Situation” – were mostly written with Gregg Jakobson (although “I Love You” is tender exception). But what really sets Bambu apart is the arrival of jazz guitarist and sometime Beach Boys sideman Carli Munoz as a writer of songs that nailed Wilson’s mile-wide romantic streak. Collectors will be familiar with tunes like “Under The Moonlight” and “All Alone” from bootlegs. But, by God, have they scrubbed up well. Bereft of the damp, flatulent drum thwacks of the bootlegs, “It’s Not Too Late” is like a bedraggled refugee from Dion’s Born To Be With You – Dennis’s sandpaper croon groping for love like a infant feels around for its mother at night. Also from Munoz, an ultra-vivid burst of Latino jazz-pop “Constant Companion” benefits from a rich dimension of choral harmonies hitherto unheard on unofficial recordings. Nearly 25 years after Dennis’s death, we’ll never know if this version of Bambu corresponds to the album that he confidently predicted would surpass Pacific Ocean Blue – especially bearing in mind the fact that this was an album that had been left abandoned by Dennis himself a full four years before he died in 1983. Friends yet to be alienated by Dennis in his final years, recall an increasingly incoherent, unstable character – who felt no need to curb the excesses that were losing him friends. In a sense that’s not surprising. The seventies had offered Dennis Wilson and his lifestyle nothing but positive reinforcement. While his brothers floundered, he did whatever he wanted to and creatively found himself in the process. Only when he lost his studio in 1978 – and, with it, the ability to record spontaneously – did that winning streak finally end. And yet, if he had regrets, he rarely voiced them. “They say I live a fast life. Maybe I just like a fast life. I wouldn't give it up for anything in the world. It won't last forever, either. But the memories will.” It seems he was right. PETER PAPHIDES

Four years ago, when Brian Wilson finally finished work on the daddy of all lost masterpieces, Smile, he did Beach Boys fans a huge favour, but also solved one of the band’s most enduring and enticing mysteries. What would people do with no need to search for that holy grail: The Great Lost Beach Boys album?

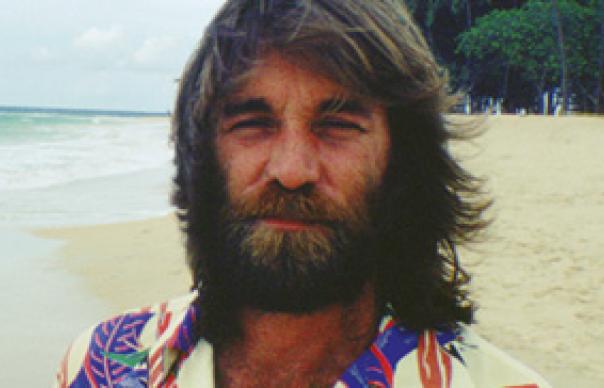

Dennis Wilson doesn’t just provide lost albums – his is almost an entirely lost career. With his only completed solo album, Pacific Ocean Blue, long deleted and its mythical successor Bambu never released, Dennis was feted chiefly by fans who had checked the credits of post-Pet Sounds albums and realised that the hirsute, handsome one on the drums had a surprisingly keen strike rate. “Cuddle Up” from Carl & The Passions/So Tough? That was his? “Forever” was Dennis too? Who knew?

Well, The Beach Boys did, of course, but it wasn’t as though they did much to nurture him. “He was under-appreciated in our band,” said Al Jardine, and certainly, using Dennis’s songs could have helped the Beach Boys out of the spot they found themselves in in the mid-70s.

Instead, when 15 Big Ones came out in 1975, effectively marking the band’s inexorable decline into becoming an oldies act, Dennis took the songs he had co-written with old pal Gregg Jakobson to Jim Guercio, head of Caribou Records – and duly became the first Beach Boy to release a solo album. Pacific Ocean Blue went head-to-head with The Beach Boys’ next album Love You, Dennis outsold his brothers by two-to-one.

In the thirty years since, Pacific Ocean Blue’s reputation has risen with the superlatives lavished up on it by fans such as The Verve, Primal Scream and The Charlatans. Unavailability has also played its part in pumping up the myth – so much so that you wonder if, heard in 2008, these songs stand to disappoint. In fact, key moments of Pacific Ocean Blue square dramatically up to your loftiest expectations.

It’s hard to talk about the opener, the Carl Wilson-assisted “River Song” in anything other than the very terminology it deploys: rising torrents of gospel harmonies, the freshwater piano trickle that starts the thing off; and the unstoppable current of Wilson’s voice, blurring nature and love into an irresistible all-consuming force. “Rainbows” is a love-drunk paean to life lived large carried effortlessly by the pistons-hissing chug of its own backing track. “Farewell My Friend” is a requiem to just-deceased Beach Boys’ associate Otto Hinsche, apparently written at the piano in a single rhapsodic outpouring to the astonishment of all present.

These are songs you could live your life to, were it not for the fact that its creator expired doing just that. You can guess what kind of a husband Dennis was to his four wives by cocking an ear to “Time”. “I’m the kind of guy who loves to mess around,” sings the sad miscreant more out of regret than pride. If Wilson’s ex-wives still seem anguished by his passing, “Thoughts Of You” goes some way to explaining why. Moving from hair-shirt minor chords and hushed, penitent assurances into a major-chord sunburst of temporary resolution, he sings “All things that live, one day must die” – and his voice hurts like you’ve never heard a Beach Boy’s voice hurt before.

On Pacific Ocean Blue, Dennis’s two sides – the boozy bon viveur and repentant child – often co-exist within the same song. Not so the songs from Bambu. The hoarse, hungover croak evokes Harry Nilsson, whose recreational habits mirrored Dennis’s own. And like Nilsson’s underrated 1972 album Nilsson Schmilsson, Bambu veers wildly between ribald, roister-doistering and achingly tender declarations of love. The reasons were simple enough here. The former songs – “School Girl”; “He’s A Bum”, “Wild Situation” – were mostly written with Gregg Jakobson (although “I Love You” is tender exception). But what really sets Bambu apart is the arrival of jazz guitarist and sometime Beach Boys sideman Carli Munoz as a writer of songs that nailed Wilson’s mile-wide romantic streak.

Collectors will be familiar with tunes like “Under The Moonlight” and “All Alone” from bootlegs. But, by God, have they scrubbed up well. Bereft of the damp, flatulent drum thwacks of the bootlegs, “It’s Not Too Late” is like a bedraggled refugee from Dion’s Born To Be With You – Dennis’s sandpaper croon groping for love like a infant feels around for its mother at night. Also from Munoz, an ultra-vivid burst of Latino jazz-pop “Constant Companion” benefits from a rich dimension of choral harmonies hitherto unheard on unofficial recordings.

Nearly 25 years after Dennis’s death, we’ll never know if this version of Bambu corresponds to the album that he confidently predicted would surpass Pacific Ocean Blue – especially bearing in mind the fact that this was an album that had been left abandoned by Dennis himself a full four years before he died in 1983.

Friends yet to be alienated by Dennis in his final years, recall an increasingly incoherent, unstable character – who felt no need to curb the excesses that were losing him friends. In a sense that’s not surprising. The seventies had offered Dennis Wilson and his lifestyle nothing but positive reinforcement. While his brothers floundered, he did whatever he wanted to and creatively found himself in the process. Only when he lost his studio in 1978 – and, with it, the ability to record spontaneously – did that winning streak finally end.

And yet, if he had regrets, he rarely voiced them. “They say I live a fast life. Maybe I just like a fast life. I wouldn’t give it up for anything in the world. It won’t last forever, either. But the memories will.” It seems he was right.

PETER PAPHIDES