The charismatic slide guitar god and Southern rock avatar finally gets his due via a massive career overview... Until now, no guitar great’s career has been as under-represented as has that of Duane Allman, who packed a lifetime’s worth of music into seven intensive and wildly productive years. Previous efforts to compile Allman’s body of work were stymied by lawsuits and massive licensing issues. It took the concerted efforts of Bill Levenson, who’d been forced to shelve an earlier attempt at a career overview while working at Universal Music in the mid-’90s, and Galadrielle Allman, Duane’s only child, who’s been on a lifelong mission to get to know her father through his music, to finally bring the long-delayed project to fruition. To say the resulting seven-disc boxset – with 129 tracks, 33 of them either previously unreleased or unissued on CD – has been worth the wait would be a gross understatement. Skydog is an addictive, endlessly captivating aural history of a towering figure in rock history, with each disc forming a distinct chapter in the sprawling narrative. The first disc, which collects 23 of Duane and brother Gregg’s initial efforts with the Escorts, which begat the Allman Joys, which in turn begat Hour Glass, spilling into brief forays with Butch Trucks’ 31st Of February and long-forgotten group the Bleus, is a microcosm of the apprenticeships undertaken by so many musicians in the mid- to late ’60s. After an initial infatuation with the Beatles, the siblings began to explore the blues and R ‘n’ B, for which they shared a deep affinity, with a fascinating side trip into the psychedelic blues of the Jeff Beck-era Yardbirds, providing a key learning experience for Duane. They then made an early attempt at making commercial records, signing a deal with Liberty Records, which renamed them Hour Glass and forced them into confining stylistic contexts. Even then, the brothers’ soulfulness showed through –after two stiff albums, they headed to Muscle Shoals and essentially drew up the blueprint for the Allman Brothers Band with foreshadowing showcases like “The B.B. King Medley” and Gregg’s “Been Gone Too Long”, only to be shot down by the label. After the stint with the 31st Of February, the brothers went their separate ways, Gregg exiled to the West Coast in an aborted attempt at a solo career, while Duane remained in Florida, playing every gig he could find, treading water. Duane’s fortunes changed in the space of a single Wilson Pickett session in late 1968 at Rick Hall’s Fame Studio in Muscle Shoals, as the young interloper wowed Hall and the seasoned session players with his prodigious natural talent, erupting Vesuvius-like on a mind-blowing cover of “Hey Jude” after being pent up for so long in Hour Glass. Disc Two compiles Duane’s session work with Pickett, Clarence Carter, Arthur Conley, Aretha Franklin, the Soul Survivors, King Curtis and others, as Hall and Atlantic’s Jerry Wexler used him extensively in early ’69, knowing they’d discovered a prodigy with jaw-dropping chops and unlimited potential. Wexler thought enough of Duane to sign him to a solo deal, and three of his early efforts are compiled on Disc Three, which encompasses the spring and summer of 1969. But he was collaborative by nature, and he apparently realized that quickly enough to abandon the project, return to Florida, and begin assembling the Allman Brothers Band with Muscle Shoals drummer Jai Johanny “Jaimo” Johanson, bassist Berry Oakley, Butch Trucks and guitarist Dickey Betts, summoning Gregg from LA to complete the lineup. But he also continued to do sessions to pay the rent while developing the band’s sound, an audaciously open-ended amalgam of blues, R&B, jazz and rock’n’roll. If Duane was a magnetic presence to his fellow musicians in Muscle Shoals, Daytona Beach and New York, he remained unknown to the rest of the world until Atlantic’s September 1969 release of Boz Scaggs, recorded at Fame and containing the 13-minute blues epic “Loan Me A Dime”, with an extended performance from Duane so withering it stopped the critics in their tracks. Two months later, The Allman Brothers Band came out, unleashing the glorious tempest of “Whipping Post”, the prototypical harmonized guitar riffage of “Black Hearted Woman” and the crushed-velvet textures of “Dreams”. A month after that, the group blew the roof off the Fillmore East for the first time. And just like that, the train was roaring down the tracks, a runaway express bound for glory. The next three discs, each capturing a few retrospectively precious months at a time, as 1969 emptied into 1970, find Duane and his simpatico bandmates converting the masses on concert stages across the States with their enthralling, force-of-nature sets, their magisterial, all-business, no bullshit stage presence a direct reflection of their leader, willowy and bent to his task, a blue-collar Michelangelo. You couldn’t take your eyes off him. While the band was kicking back in Macon, enjoying the downtime, the tireless guitarist was showing up at sessions for everyone worth a damn from Ronnie Hawkins to Lulu, from Sam the Sham to Herbie Mann, changing the climate of every tracking room he entered. His abiding relationship with the knowing engineer/producer Tom Dowd led to Idlewild South and a few ecstatic nights at Criteria in Miami with Eric Clapton and his Dominos making what may be the most exalted example ever of dueling electric guitars. Disc Seven, charting what would be the last few months of his life – an acoustic workout with Delaney and Bonnie for New York’s WPLJ in July, an Allmans stop at the same station a month later, live and studio recordings from September, topped by the penultimate cut, an immersive 18-minute “Dreams”. Then, finally, the only recording that could end this opus, the shimmering acoustic duet with Dickey “Little Martha”, its heartbreaking beauty intensified by the cumulative tidal force of the music that preceded it, while being reminded of the first time we heard it, on Eat A Peach, not long after we lost him. If Duane Allman’s purpose in life was to play the guitar, his daughter’s purpose appears just as clearly to give voice to her father’s wordless expressiveness. Galadrielle, who’s finishing a book about her father, captures his prodigious soulfulness more vividly than anyone else who has yet attempted to do so in her notes to Skydog. “His spirit shines through every song,” she writes. “There is something forever unknowable in his music, a mystery I cannot solve by listening, an element that is wholly his own and does not translate into words. Music told the truth. He grabbed on to it from the very beginning and never let it go.” Amen. Bud Scoppa Photo credit: John Gellman

The charismatic slide guitar god and Southern rock avatar finally gets his due via a massive career overview…

Until now, no guitar great’s career has been as under-represented as has that of Duane Allman, who packed a lifetime’s worth of music into seven intensive and wildly productive years. Previous efforts to compile Allman’s body of work were stymied by lawsuits and massive licensing issues. It took the concerted efforts of Bill Levenson, who’d been forced to shelve an earlier attempt at a career overview while working at Universal Music in the mid-’90s, and Galadrielle Allman, Duane’s only child, who’s been on a lifelong mission to get to know her father through his music, to finally bring the long-delayed project to fruition.

To say the resulting seven-disc boxset – with 129 tracks, 33 of them either previously unreleased or unissued on CD – has been worth the wait would be a gross understatement. Skydog is an addictive, endlessly captivating aural history of a towering figure in rock history, with each disc forming a distinct chapter in the sprawling narrative.

The first disc, which collects 23 of Duane and brother Gregg’s initial efforts with the Escorts, which begat the Allman Joys, which in turn begat Hour Glass, spilling into brief forays with Butch Trucks’ 31st Of February and long-forgotten group the Bleus, is a microcosm of the apprenticeships undertaken by so many musicians in the mid- to late ’60s. After an initial infatuation with the Beatles, the siblings began to explore the blues and R ‘n’ B, for which they shared a deep affinity, with a fascinating side trip into the psychedelic blues of the Jeff Beck-era Yardbirds, providing a key learning experience for Duane. They then made an early attempt at making commercial records, signing a deal with Liberty Records, which renamed them Hour Glass and forced them into confining stylistic contexts.

Even then, the brothers’ soulfulness showed through –after two stiff albums, they headed to Muscle Shoals and essentially drew up the blueprint for the Allman Brothers Band with foreshadowing showcases like “The B.B. King Medley” and Gregg’s “Been Gone Too Long”, only to be shot down by the label. After the stint with the 31st Of February, the brothers went their separate ways, Gregg exiled to the West Coast in an aborted attempt at a solo career, while Duane remained in Florida, playing every gig he could find, treading water.

Duane’s fortunes changed in the space of a single Wilson Pickett session in late 1968 at Rick Hall’s Fame Studio in Muscle Shoals, as the young interloper wowed Hall and the seasoned session players with his prodigious natural talent, erupting Vesuvius-like on a mind-blowing cover of “Hey Jude” after being pent up for so long in Hour Glass. Disc Two compiles Duane’s session work with Pickett, Clarence Carter, Arthur Conley, Aretha Franklin, the Soul Survivors, King Curtis and others, as Hall and Atlantic’s Jerry Wexler used him extensively in early ’69, knowing they’d discovered a prodigy with jaw-dropping chops and unlimited potential.

Wexler thought enough of Duane to sign him to a solo deal, and three of his early efforts are compiled on Disc Three, which encompasses the spring and summer of 1969. But he was collaborative by nature, and he apparently realized that quickly enough to abandon the project, return to Florida, and begin assembling the Allman Brothers Band with Muscle Shoals drummer Jai Johanny “Jaimo” Johanson, bassist Berry Oakley, Butch Trucks and guitarist Dickey Betts, summoning Gregg from LA to complete the lineup. But he also continued to do sessions to pay the rent while developing the band’s sound, an audaciously open-ended amalgam of blues, R&B, jazz and rock’n’roll.

If Duane was a magnetic presence to his fellow musicians in Muscle Shoals, Daytona Beach and New York, he remained unknown to the rest of the world until Atlantic’s September 1969 release of Boz Scaggs, recorded at Fame and containing the 13-minute blues epic “Loan Me A Dime”, with an extended performance from Duane so withering it stopped the critics in their tracks. Two months later, The Allman Brothers Band came out, unleashing the glorious tempest of “Whipping Post”, the prototypical harmonized guitar riffage of “Black Hearted Woman” and the crushed-velvet textures of “Dreams”. A month after that, the group blew the roof off the Fillmore East for the first time. And just like that, the train was roaring down the tracks, a runaway express bound for glory.

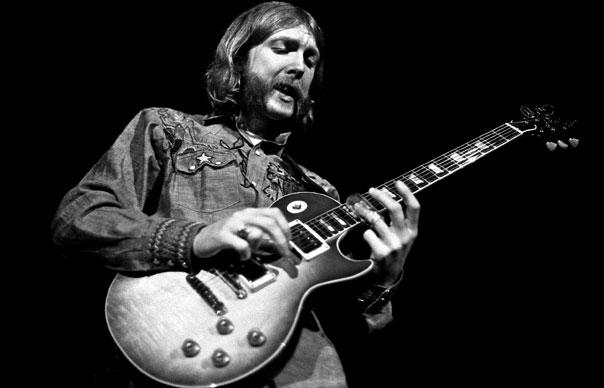

The next three discs, each capturing a few retrospectively precious months at a time, as 1969 emptied into 1970, find Duane and his simpatico bandmates converting the masses on concert stages across the States with their enthralling, force-of-nature sets, their magisterial, all-business, no bullshit stage presence a direct reflection of their leader, willowy and bent to his task, a blue-collar Michelangelo. You couldn’t take your eyes off him.

While the band was kicking back in Macon, enjoying the downtime, the tireless guitarist was showing up at sessions for everyone worth a damn from Ronnie Hawkins to Lulu, from Sam the Sham to Herbie Mann, changing the climate of every tracking room he entered. His abiding relationship with the knowing engineer/producer Tom Dowd led to Idlewild South and a few ecstatic nights at Criteria in Miami with Eric Clapton and his Dominos making what may be the most exalted example ever of dueling electric guitars. Disc Seven, charting what would be the last few months of his life – an acoustic workout with Delaney and Bonnie for New York’s WPLJ in July, an Allmans stop at the same station a month later, live and studio recordings from September, topped by the penultimate cut, an immersive 18-minute “Dreams”. Then, finally, the only recording that could end this opus, the shimmering acoustic duet with Dickey “Little Martha”, its heartbreaking beauty intensified by the cumulative tidal force of the music that preceded it, while being reminded of the first time we heard it, on Eat A Peach, not long after we lost him.

If Duane Allman’s purpose in life was to play the guitar, his daughter’s purpose appears just as clearly to give voice to her father’s wordless expressiveness. Galadrielle, who’s finishing a book about her father, captures his prodigious soulfulness more vividly than anyone else who has yet attempted to do so in her notes to Skydog. “His spirit shines through every song,” she writes. “There is something forever unknowable in his music, a mystery I cannot solve by listening, an element that is wholly his own and does not translate into words. Music told the truth. He grabbed on to it from the very beginning and never let it go.”

Amen.

Bud Scoppa

Photo credit: John Gellman