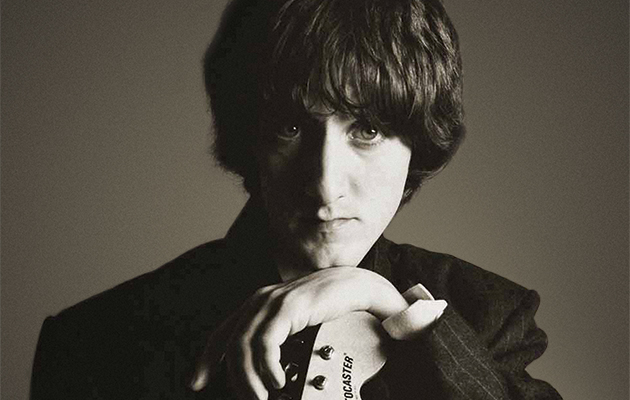

“Vini Reilly, by the way, is way overdue a revival,” says God, appearing to Tony Wilson in a hash-haze vision towards the end of 24 Hour Party People. “You might want to think about a greatest hits.” It’s played for laughs, but there’s an important truth here: in many ways, Wilson’s persistent attempts to usher the guitarist into the spotlight of popular acclaim was the secret driver of the whole quixotic Factory escapade.

The Factory club was first founded in 1978, after all, expressly to promote the “neo-psychedelia” of the Column’s first misfiring incarnation, and Factory Records formed in 1979 to release the group’s music (the fledgling Joy Division at this time being almost an afterthought). You could even see Factory Classical, one of the most noble fiascos of the entire enterprise, as an attempt to conjure a context for Reilly’s quasi-classical meanderings – notably Without Mercy (1984), part of Wilson’s campaign to cultivate Reilly as Withington’s answer to Bohuslav Martinů.

1985 seemed to mark another change of tack, with Wilson stuffing Reilly’s Christmas stocking with sequencers and electronic paraphernalia. Although it was never expressly stated, you get the feeling that Wilson might have been pushing Reilly towards soundtrack work. And it’s maybe not that great a stretch to think of a possible world where Reilly developed as a kind of post-punk Mark Knopfler, plangently scoring wistful widescreen accounts of post-industrial decay.

On 1986’s Circuses And Bread, with tracks like “Dance 1”, Reilly was evidently still getting to grips with the technology (Melody Maker compared it to testcard music), but for The Guitar And Other Machines (Nov 1987), things were falling into place. Producer Stephen Street was brought in (paving the way for Reilly’s crucial role on Morrissey’s Viva Hate), and synthetic elements were grafted into the Durutti soundworld more seamlessly.

“Arpeggiator” is a stunningly bold statement of intent – it’s like the hitherto frail, musical Durutti corpus has been augmented into some six-million-dollar bionic body. Longtime Durutti Columnist John Metcalfe’s viola, plucked and bowed, swoops over a scintillating torrent of synths, before the track erupts into powerchords and molten lead guitar.

“What Is It To Me (Woman)” is a more characteristic Durutti excursion, but played out on a wider screen, the decaying reverbed guitar lines intertwined with desolate piano and washed over with wailing harmonica. Wilson had often despaired of Reilly’s reluctance to spend more than a couple of days in the studio, but Stephen Street seems to have persuaded him of the virtues of a more diligent approach – it’s like the home movies or chamber pieces of the early albums have suddenly been recast in cinemascope. “Red Shoes”, then, is an appropriate title, conjuring associations with Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s Technicolor fantasia. Sensing the way the marketplace was changing, Factory ensured …Other Machines was the first LP to be released on DAT – Wilson once again vainly trying to steer the nascent yuppie audiophile market away from Brothers In Arms to more esoteric in-car entertainments.

This exemplary reissue augments the original LP with a number of fugitive pieces from the Durutti discography: notably the “Greetings Three” EP, originally released in Italy in 1986, plus a handful of tracks cut in LA and released as the “City Of Our Lady” EP in August ’87 – remarkable for a barmy cover of “White Rabbit”.

The third disc, meanwhile, unearths a live recording from the conclusion of the US tour, at the Bottom Line club in New York, previously available only on cassette. It’s hard to say the live set adds much to the studio incarnation of the …Other Machines material – “Arpeggiator” feels like it’s been diminished from IMAX to church hall, an undoubtedly sublime guitarist playing along with some MIDI backing tracks. It’s only on tracks like “Jacqueline”, where Reilly really locks into a groove with drummer Bruce Mitchell, that the music comes alive and you sense the magic that still eludes the machines.

Q&A

Bruce Mitchell, Durutti Column drummer

and manager

Did Vini listen to the album again for this reissue?

Vini doesn’t really listen to his old stuff now. He likes the artefacts, though, the finished products. He puts them on his wall.

A lot of the album feels like it might be auditioning for soundtracks – was that a conscious intention?

Vini has only ever made music for himself. Tony Wilson always thought the music would come to film, but it’s only in the last couple of years that it has started showing up on soundtracks [and on Jerry Maguire, 1996].

It was sad to hear about Vini’s ongoing health problems – how’s he doing now?

He’s going to be playing in March. After the strokes it was hard for him. We bought him a special instrument with a narrow neck, but when we went to see him he had his old Strat set up and was roaring away! He frequently rediscovers his mojo. We’ve got an LP all ready to be released, but he’s having a bit of a dispute with the producer. Vini has his ups and downs, you know, but he’s still functioning in his unique way. STEPHEN TROUSSÉ