It’s remarkable enough that these 12 songs exist. In 2005, the former Orange Juice singer endured two strokes, which left his right arm paralysed. He also suffers from dysphasia, which causes problems with clarity of speech. Edwyn’s recovery has been slow and difficult, as chronicled by his partner (and manager) Grace Maxwell in her book, Falling And Laughing. But his subsequent live performances have demonstrated the importance of music to his renewal. The dysphasia might get in the way of free-flowing conversation, but onstage, with a band, Edwyn’s singing is relatively unimpaired. True, in his earliest live outings there were a few wayward moments, but Edwyn’s voice has always had its little idiosyncrasies. With each performance, he seems to have grown in confidence. The medical causes are different, but a comparison to Brian Wilson isn’t entirely fanciful. The first impression is one of gratitude that any kind of performance is possible. Then the songs take over. In Edwyn’s case, this is quite strange, because even in the Postcard days he was writing about emotional fragility. Listening to “Falling And Laughing” now – with its lyrics about loneliness and pain, and fall-falling again – is almost unbearably poignant. Enough special pleading. Losing Sleep is a great record, period. True, it’s not like Edwyn’s later solo work, where his wit and an acerbic worldview were locked in a stern embrace. It’s a punk rock record, pure and simple, harking back to what Edwyn now calls “the Orange Juice days”, almost as if he is referring to a distant, half-forgotten era. That’s punk in its original conception: urgent words and rude melodies. It’s music for cheap transistors, with rattling drums and siren guitars, and rhythms that clatter like a Motown 45 at a youth club disco. It sounds great on cheap speakers. Listen closely, though, and there is an emotional arc running through the record, from the confusion of “Losing Sleep”, through “Humble” and “Bored” to the joyful “Over The Hill” (so named, because the singer isn’t). It’s regrettable, of course, that Edwyn’s guitar is missing. But that absence – and it is significant; he is one of the great post-punk guitarists – is bridged by the contributions of his collaborators. “What Is My Role” – a duet with Ryan Jarman of The Cribs – has undeveloped lyrics, and a sneering, ringing tune with a scything guitar borrowed from The Ruts’ “Babylon’s Burning”. Jarman also contributes vocals to the grimy, rushing “I Still Believe In You”, which adds a chiming organ to a punk tune, as Edwyn consoles himself about the siren voices running around his brain. It’s hard not to conclude that the song is really about self-belief. Alex Kapranos and Nick McCarthy of Franz Ferdinand bring their Teutonic disco chanting, and a synth that sounds like an electric flycatcher to “Do It Again”. Johnny Marr’s guitar brings a nasty note to “Come Tomorrow, Come Today” – a choppy, Orange Juice-like tune punctuated by a Morse code bleep. “In Your Eyes” (co-written with The Drums) is another rumbling duet, with Edwyn noting that “the politics of life are obscure”, and looking forward to a scenic life away from the city. Romeo Stodart of The Magic Numbers co-writes, and sings very sweetly on, “It Dawns On Me” a summery song in praise of the simple life. After all this gorgeous clatter, the sparse “All My Days” comes as a shock, but it’s a beautiful surprise, with Edwyn’s vulnerability laid bare against Roddy Frame’s jazzy guitar. The record closes with “Searching For The Truth”, the song Edwyn sang as an encore at his earliest comeback concerts. Back then, when hearing Edwyn sing anything seemed like a little miracle, this song was unbearably poignant. Now, intoned starkly against Carwyn Ellis’ guitar, the optimism shines more strongly than the sense of stubborn endurance. “Some sweet day, we’ll get there in the end,” Edwyn croons. It’s a hopeful promise, and a sad lament. Alastair McKay Q+A Edwyn Collins How long after your illness was it before you started writing songs again? Apart from a snatch of “Searching For The Truth” it was almost four years after my stroke, November 2008. For a while my thoughts were indistinct. Then suddenly, I had music in my head again. Incredible. In the middle of the night I had an idea. I lay awake thinking it through. I woke Grace up – “Write this down!” That was “Losing Sleep”. How did you adapt to writing without playing guitar? I got a little Sony cassette dictation machine. I sing lyric ideas and guitar parts, anything. Then in the studio, I explain to my muso friends the ideas. I may give them a clue. “Ramsey Lewis!” “AC/DC!” And I can still make chord shapes on the guitar while someone strums. These songs seem very direct… was that deliberate? I like fast songs now. Direct and focused, clear and decisive. I record fast. I want people to hear the excitement of the moment. The mood is optimistic. Is that how you feel? Definitely. Why not, indeed? I’ve got my life back, all my work, my friends around me, family, all that. And my audience. I’m very spoilt and very lucky. I’m aware of that fact, acutely. INTERVIEW: ALASTAIR McKAY

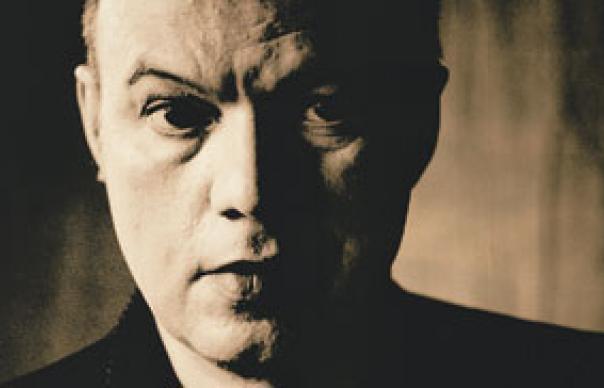

It’s remarkable enough that these 12 songs exist. In 2005, the former Orange Juice singer endured two strokes, which left his right arm paralysed. He also suffers from dysphasia, which causes problems with clarity of speech.

Edwyn’s recovery has been slow and difficult, as chronicled by his partner (and manager) Grace Maxwell in her book, Falling And Laughing. But his subsequent live performances have demonstrated the importance of music to his renewal. The dysphasia might get in the way of free-flowing conversation, but onstage, with a band, Edwyn’s singing is relatively unimpaired. True, in his earliest live outings there were a few wayward moments, but Edwyn’s voice has always had its little idiosyncrasies. With each performance, he seems to have grown in confidence.

The medical causes are different, but a comparison to Brian Wilson isn’t entirely fanciful. The first impression is one of gratitude that any kind of performance is possible. Then the songs take over. In Edwyn’s case, this is quite strange, because even in the Postcard days he was writing about emotional fragility. Listening to “Falling And Laughing” now – with its lyrics about loneliness and pain, and fall-falling again – is almost unbearably poignant.

Enough special pleading. Losing Sleep is a great record, period. True, it’s not like Edwyn’s later solo work, where his wit and an acerbic worldview were locked in a stern embrace. It’s a punk rock record, pure and simple, harking back to what Edwyn now calls “the Orange Juice days”, almost as if he is referring to a distant, half-forgotten era.

That’s punk in its original conception: urgent words and rude melodies. It’s music for cheap transistors, with rattling drums and siren guitars, and rhythms that clatter like a Motown 45 at a youth club disco. It sounds great on cheap speakers. Listen closely, though, and there is an emotional arc running through the record, from the confusion of “Losing Sleep”, through “Humble” and “Bored” to the joyful “Over The Hill” (so named, because the singer isn’t).

It’s regrettable, of course, that Edwyn’s guitar is missing. But that absence – and it is significant; he is one of the great post-punk guitarists – is bridged by the contributions of his collaborators. “What Is My Role” – a duet with Ryan Jarman of The Cribs – has undeveloped lyrics, and a sneering, ringing tune with a scything guitar borrowed from The Ruts’ “Babylon’s Burning”. Jarman also contributes vocals to the grimy, rushing “I Still Believe In You”, which adds a chiming organ to a punk tune, as Edwyn consoles himself about the siren voices running around his brain. It’s hard not to conclude that the song is really about self-belief.

Alex Kapranos and Nick McCarthy of Franz Ferdinand bring their Teutonic disco chanting, and a synth that sounds like an electric flycatcher to “Do It Again”. Johnny Marr’s guitar brings a nasty note to “Come Tomorrow, Come Today” – a choppy, Orange Juice-like tune punctuated by a Morse code bleep. “In Your Eyes” (co-written with The Drums) is another rumbling duet, with Edwyn noting that “the politics of life are obscure”, and looking forward to a scenic life away from the city. Romeo Stodart of The Magic Numbers co-writes, and sings very sweetly on, “It Dawns On Me” a summery song in praise of the simple life.

After all this gorgeous clatter, the sparse “All My Days” comes as a shock, but it’s a beautiful surprise, with Edwyn’s vulnerability laid bare against Roddy Frame’s jazzy guitar. The record closes with “Searching For The Truth”, the song Edwyn sang as an encore at his earliest comeback concerts. Back then, when hearing Edwyn sing anything seemed like a little miracle, this song was unbearably poignant. Now, intoned starkly against Carwyn Ellis’ guitar, the optimism shines more strongly than the sense of stubborn endurance. “Some sweet day, we’ll get there in the end,” Edwyn croons. It’s a hopeful promise, and a sad lament.

Alastair McKay

Q+A Edwyn Collins

How long after your illness was it before you started writing songs again?

Apart from a snatch of “Searching For The Truth” it was almost four years after my stroke, November 2008. For a while my thoughts were indistinct. Then suddenly, I had music in my head again. Incredible. In the middle of the night I had an idea. I lay awake thinking it through. I woke Grace up – “Write this down!” That was “Losing Sleep”.

How did you adapt to writing without playing guitar?

I got a little Sony cassette dictation machine. I sing lyric ideas and guitar parts, anything. Then in the studio, I explain to my muso friends the ideas. I may give them a clue. “Ramsey Lewis!” “AC/DC!” And I can still make chord shapes on the guitar while someone strums.

These songs seem very direct… was that deliberate?

I like fast songs now. Direct and focused, clear and decisive. I record fast. I want people to hear the excitement of the moment.

The mood is optimistic. Is that how you feel?

Definitely. Why not, indeed? I’ve got my life back, all my work, my friends around me, family, all that. And my audience. I’m very spoilt and very lucky. I’m aware of that fact, acutely.

INTERVIEW: ALASTAIR McKAY